It was the creation of Yugoslavia that involved the most dramatic transformation, ethnically and territorially, in the settlement of the Balkans. Serbia, Vojvodina, Slovenia, Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia, Bosnia-Hercegovina and Montenegro were united under the King of Serbia on 1 December 1918, over a month before the opening of the Peace Conference in Paris. This union of South Slavs apparently brought the troubled history of Serbia to a victorious conclusion, with enemies old and new, Ottoman, Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian, completely vanquished. Of course, the question of whether it was Greater Serbia that was made, as opposed to a genuine union of South Slavs, was destined to undermine and ultimately to destroy the new state. There was no conclusion and, in the long run, no victory. But this did not reflect the failure of the Peace Conference, which did not create Yugoslavia: “we had nothing to do with it… [The Yugoslavs] proclaimed themselves a happy band of brothers and launched their ship upon the angry waters of Europe as a sovereign state.”[1] The Peace Conference failed in a very different way, when the statesmen walked away and left the most difficult question, between Yugoslavia and Italy, unresolved.[2]

The Adriatic Question

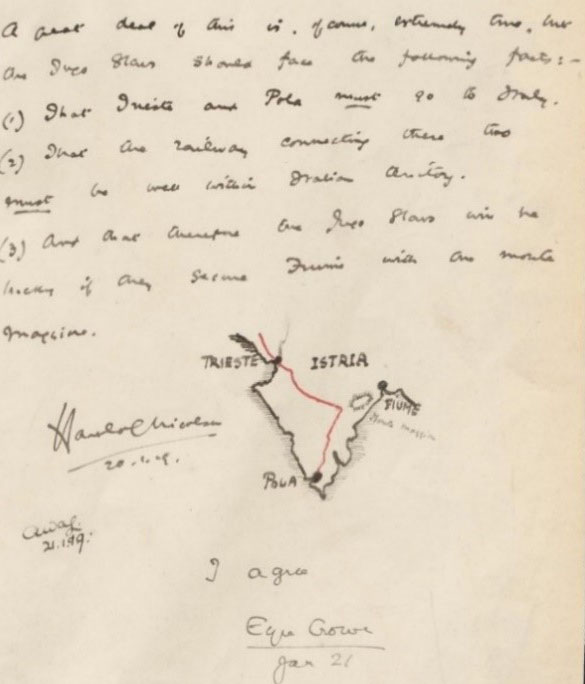

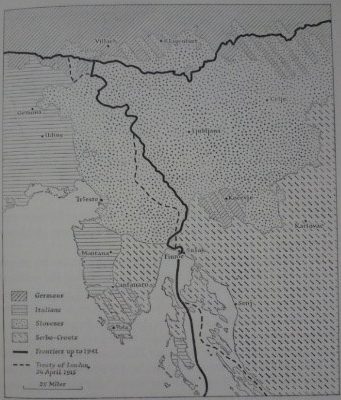

The political leaders who met in Paris in 1919 had to decide how the southern parts of the defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire would be shared between Austria, Hungary, Italy and Yugoslavia. These countries made conflicting claims and the animosity between Italy and Yugoslavia was especially bitter. The British and French had more respect for “Heroic Serbia” than for Italy (“the boys who scampered away from Caporetto” in 1917 – Clemenceau).[3] However, the Allies were not prepared to indulge Yugoslav demands for places with Italian majorities. Harold Nicolson considered a Yugoslav claim for Trieste and Gorizia (north of Trieste) “a quite impossible solution. It is the greatest mistake on the part of the Jugo Slavs to advance such impracticable claims – which only serve to compromise their more justifiable interests.” The Yugoslavs “should face the following facts:– (1) That Trieste and Pola must go to Italy. (2) That the railway connecting these two must be well within Italian territory…”[4] Nicolson’s drawn map, showing this railway line (in red), made it clear that most of Istria would have to go to Italy. The scholars of the American Inquiry were in agreement on these points, giving central and western Istria and Gorizia and Trieste to Italy.[5] At the Council on 18 February, Foreign Minister Ante Trumbić claimed allof the former Austro-Hungarian territory which contained Slavs, including largely Italian Gorizia, Trieste and western Istria. Nicolson was furious: “The idiots claim Trieste,” he wrote, lamenting “the idiocy of Croat and Slovene claims to Gorizia and Trieste”.[6] The Yugoslav claims were received in Italy “with considerable satisfaction” as they revealed “the unreasonable pretensions” of their opponents.[7] Or, as Prime Minister Orlando put it, “Things are going well. The excesses of Yugoslav megalomania are in our favour.”[8]

The main problem, the source of so much tension in the Conference, was the difference between Italy and the United States. The Italians were determined to secure all of Istria, Fiume and central Dalmatia, while the Americans, not bound by the wartime treaty (the Treaty of London of 1915) which promised most of these to Italy, were, consistent with Wilsonian ideas, respectful of the Slav majority in a large part of the disputed territory. During April 1919, when the Yugoslav claim to Trieste was quietly abandoned and Italy’s Orlando did not prioritise Dalmatia, the future of Fiume emerged as the core issue, arguably “the storm-centre of the whole Conference”.[9] Fiume, a flourishing port on the coastline north of Dalmatia, was seen as a vital economic asset for Yugoslavia, its outlet on the Adriatic. The city had more Italians than Slavs, but Italians were slightly outnumbered (26,000 to 25,000) when the adjoining suburb of Sušak was included, and if, as generally presumed, Fiume’s hinterland were to remain attached to the city, there would be a sizeable Slav majority. Inclusion of the hinterland meant “incorporating a solid Croat population of 100,000 for the sake of the 25,000 Italians resident in the actual town of Fiume”.[10]

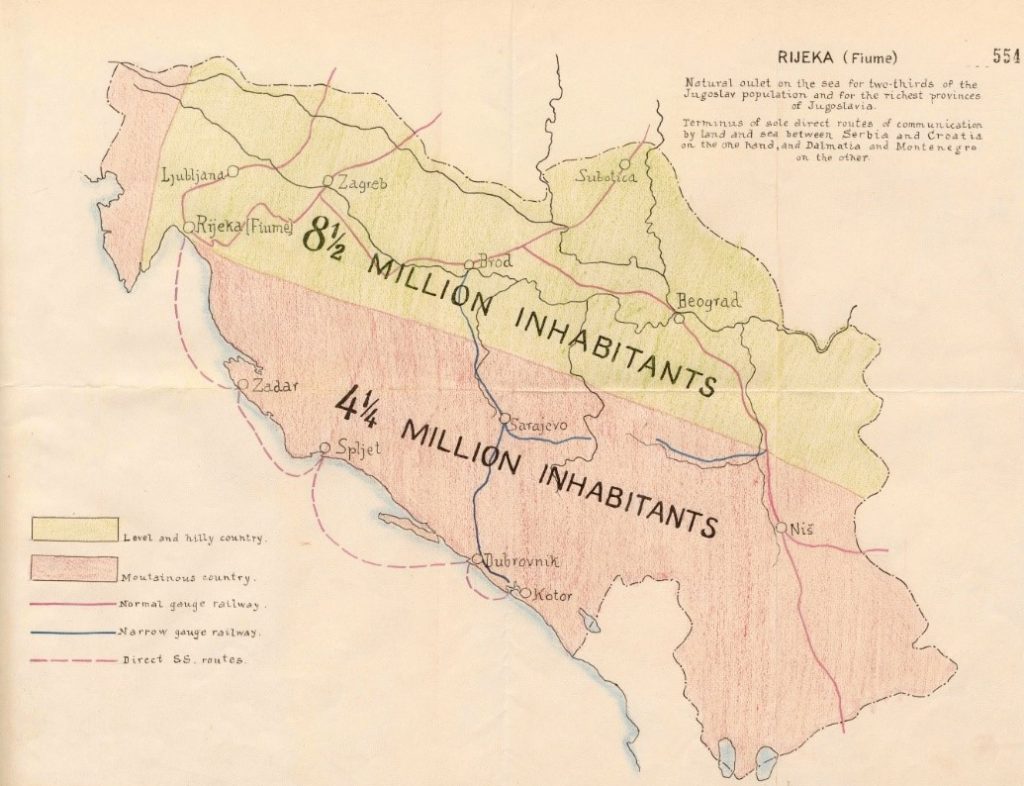

Sir Eyre Crowe and Allen Leeper were impressed by both the economic and ethnographical arguments of the Yugoslavs and reacted positively (“The map is very convincing” – Hardinge) to their claim that only Fiume (Rijeka), with railway connections to the interior, served the richest and most populous part of the new state.[11] But the Americans were split between pragmatists (Edward House, David Miller and Sidney Mezes, all senior within the delegation) and idealists (the regional experts, including Charles Seymour and Douglas Johnson). The latter feared that Wilson might be persuaded to trim towards the Italians, not least because he needed their support for the League of Nations.[12]

Wilson initially hedged, entertaining the possibility that Fiume might have some sort of free-city status, perhaps under the League, with guaranteed access to the port (but not sovereignty) for Yugoslavia. However, in response to Orlando’s inflexibility – “We don’t wish to abandon our brothers, whose liberation was the great goal of our national war”[13] – the President insisted in the Council on 19 and 20 April 1919 that Fiume could not be given to Italy. On 23 April, Wilson famously issued a public statement in which he refused to honour the Treaty of London, the basis of most of Italy’s claims, and affirmed that Fiume could not go to Italy. Orlando, furious that Wilson had appealed over his head to the Italian people, walked out of the Peace Conference; he left for Rome on 24 April – “in dramatic, although somewhat prearranged, indignation,” wrote Nicolson, whose diary verdict was “Good riddance” – with Sonnino following two days later.[14] Wilson’s move failed in that, far from convincing the Italian people, the letter produced a storm of nationalist indignation in Italy. The Italian leaders soon returned to Paris, arriving just in time to receive the Germans on 7 May; Lloyd George’s mistress had them “returning in a hurry with their tails between their legs – as someone suggested, ‘fiuming’ – in order, it is presumed, to be in at the finish.”[15]

The gap between Orlando and Wilson (and the Yugoslavs) proved unbridgeable, with differences on eastern Istria and Dalmatia as well as Fiume. During May, America’s Douglas Johnson produced a plan which would have given the Yugoslavs what they wanted through a series of local plebiscites, while Colonel House and André Tardieu proposed to put most of the disputed territory under the League. Wilson was “inflexible in his determination to yield nothing” (House), clinging to “his principle that no peoples should be handed over to another rule without their consent”.[16] He told his father’s entertaining story about a confused little pig which continually found itself back where it started![17] The talks led nowhere and all accepted that, as Wilson put it. “We must proceed to other business and not dilly-dally with the Italians any more.”[18] Orlando, “baulked of annexations desired to still his mob” (Vansittart), now faced a storm at home. When the Italian Parliament met on 19 June, he was defeated by a large majority (259-78) and forced to resign.[19]

With the Allies tied up dealing with Germany, the problem of the Adriatic was left in abeyance for many weeks. The negotiations of the following months, between July 1919 and January 1920, are less studied, perhaps for the very good reason that they led nowhere, but they do shed light on the tension between pragmatism and principle, the impact of events on the ground, and the unscrupulousness of David Lloyd George. Italy’s new Prime Minister, Francesco Nitti – “a stout little fellow with a big round head”[20] – and Tommaso Tittoni, the Foreign Minister who went to Paris in July 1919, had neither Orlando’s infatuation with Fiume nor Sonnino’s fixation on the Treaty of London. By mid-September, a compromise settlement seemed achievable. The Italians accepted that Fiume would have some sort of international status, under the League, and Wilson reluctantly conceded that there would be no recourse to the plebiscite that he had hoped would deliver Fiume to Yugoslavia after a few years. In addition, the Italians accepted the loss of eastern Istria and almost all of Dalmatia, while the Yugoslavs would give up on western Istria and Trieste.[21]

L’epopea dannunziana

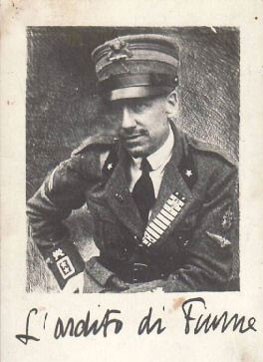

This progress towards a settlement was rudely interrupted when Gabriele d’Annunzio seized Fiume. The Italian army had occupied Fiume from mid-November 1918 and was joined there by smaller contingents of Americans (who left in February), British and French. The French soldiers, openly favouring the Yugoslav cause, clashed frequently with armed Italians (“the Fiumani”) in June and July 1919, culminating in the murder of thirteen of the French, nine on 6 July alone (“they literally cut those poor little Chinks [Vietnamese] into pieces”).[22] An Allied commission of inquiry advised dissolving the (Italian) National Council which had governed Fiume and a drastic reduction of the Italian army’s presence. Published (leaked) in Italy at the start of September, the report was seen as a threat to Italian control of Fiume. The time had arrived for the long-feared nationalist coup, which took the form of Gabriele d’Annunzio’s seizure of Fiume. D’Annunzio, writer, aesthete and war hero, the self-styled “poet of slaughter”, led a column of about 2,500 soldiers into Fiume on 12 September and claimed the city for Italy.

Nitti’s government now reinforced (or revived) its demand for Fiume to prevent a full-scale nationalist revolution in Italy. This was implicit in Foreign Minister Tittoni’s 17 September appeal to Wilson, when he backed a Clemenceau plan to give the port to the League, the city to Italy and the hinterland to Yugoslavia: “[V]ery much distressed,” he “begged” chief-delegate Frank Polk to send his “personal appeal” to Wilson “urging the acceptance of Fiume as an Italian city”. Polk felt “genuinely sorry for Tittoni, as Lloyd George and Clemenceau [have] upset him by their favourable attitude and, further than that, the acceptance at this moment of any plan which would deprive Italy of Fiume would be political suicide for him, in view of the occupation of Fiume by D’Annunzio.[23] Nitti pressed Wilson six days later: “Everything can be calmed by the recognition of Fiume to us… [You] cannot but wish to weigh the new and tragic elements which have intervened… I respectfully implore your immediate word of deliverance…”[24]

Clemenceau supported Tittoni’s appeal to Wilson because of the “serious crisis” in Italy and, rather than demanding action against d’Annunzio, the British (through ambassador Rodd and Harold Nicolson) acknowledged the government’s “impotence” in the face of widespread public and armed forces support for the “popular hero”.[25] The Allies imposed a naval blockade on Fiume to complement the efforts of the Italian troops “blockading it from the land side” – but the land blockade was a “transparent sham” as Italian soldiers and officials colluded with the insurrectionists, and little could be done to stop the thousands of volunteers who rushed to “la Mecca italiana”.[26]

There may have been a mixture of opportunism and desperation in the Italian decision to raise the stakes when negotiations flickered into life again in mid-October 1919. Tittoni proposed that the town of Fiume should have “absolute independence” as a separate city state – which he knew would inevitably be run by the local Italians – and, the novel feature, that Italy should have “the coast strip uniting the Italian part of the Istrian peninsula with the town of Fiume so that the town was territorially connected with Italy”.[27] The population of the coastal strip was Slav (albeit small: it was mostly “a narrow strip of barren beach”) and its possession would bring Italian forces to the gates of Fiume and enable Italy to threaten the railway line from Fiume to Laibach (Ljubljana). So, the coastal strip element ensured that the Americans (through Secretary Lansing on 27 October) rejected the plan.[28]

Lloyd George now wavered, pushing for acceptance of Italy’s demands: he felt that the Adriatic dispute hampered agreement over Asia Minor, his priority, and Nitti had appealed to him to save Italy from the “dangerous” situation created by the Fiume crisis.[29] In a telegram to Wilson on 31 October, the British Premier urged “the importance of not precipitating a serious crisis” in Italy over “points which are not of real principle”. He commended the “moderation” of Nitti’s views and found only a “narrow margin” separating Nitti and Wilson, and, music to Italian ears, he recalled the contrast between Italy’s “efforts and sacrifices” in the war and the way that the Croats and Slovenes, soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army, had been enemies “to the last”.[30] The Americans would not be moved, however, and the joint memorandum signed by the Big Three’s delegation leaders (Polk, Sir Eyre Crowe and Clemenceau) on 9 December was essentially a statement of the American position: Fiume and its hinterland, the coastal strip and eastern Istria would be in a new international state under the League.[31]

The Sprünge of Lloyd George

Ominously, although Clemenceau signed up, his private observation heralded the problems that lay ahead: “The Americans are charming, but they are far away. When they have gone the Italians remain and as our neighbours!”[32] Seymour later made much of the fact that neither Clemenceau nor Lloyd George was actively concerned in drafting the 9 December memorandum.[33] The British and French met the Italians in Paris during December, behind the backs of the Yugoslavs, Crowe referring at one point to “the Yugoslavs[,] from whom the negotiations with Italy have been kept entirely secret”.[34] Early in January 1920, all of the interested parties (except for the Americans) gathered in London to consider a fresh initiative by Lloyd George and Clemenceau. The Big Three (no longer including Wilson, of course, but Nitti was there as “both pleader and judge”[35]) made the key decisions on 12-14 January. Allen Leeper’s diary shows that on 12 and 13 January, Italy “was conceded Fiume town & a coastal strip connecting it with Italy…Italian sovereignty over town of Fiume” – but on the 14th, after the Yugoslav delegation refused to budge, “Clemenceau persuaded Nitti to concede Fiume to be Free City, not Italian.”[36] The “January Compromise” of 14 January 1920 meant abandonment of the whole concept of a buffer state. It made Fiume (and Zara) independent “with the right to choose its own diplomatic representation”; and it gave Italy the coastal strip to Fiume and territory around Senosecchia, and pushed the frontier well to the east of the so-called Wilson Line in Istria. But Yugoslavia would have almost all of Dalmatia.[37]

The plan was so far removed from American thinking that it surely reflected the depreciation of Wilson’s influence as, far away in Washington, he recovered slowly from the paralytic stroke suffered in October and struggled vainly with the Republican opponents of the League of Nations. Lloyd George was the driving force in the January negotiations. Seemingly free of the shackles of Wilson, and with Clemenceau about to fall in France, he was now the dominant personality of the Peace Conference and he was determined to shape and settle all remaining questions. Impelled more by his desire for a settlement than any ideals, he told the Council that Fiume was “not really a question of any intrinsic importance” and that “the only thing to do was to reach some rough and ready solution which all parties could accept”.[38] Clemenceau was important as chief persuader, or arm-twister, browbeating Yugoslavia’s Pašić and Trumbić: “If you say ‘No’, the Treaty of London will have to settle matters… You will get nothing in Dalmatia.” He strongly attacked the Yugoslavs on 14 January, distinguishing between the reasonable Serbs, wartime allies, and “uncompromising” Croats, the former enemy – a distinction quickly repudiated by both Pašić (the Serb) and Trumbić (the Croat).[39]

The Yugoslavs could not agree to the award of largely-Slav Senosecchia, eastern Istria and the coastal strip to Italy. They accepted the independence of Fiume and Zara, and did not demand future plebiscites, but they wanted Yugoslav management of the port at Fiume and protested that allowing these cities to choose their diplomatic representatives “would amount to a disguised annexation” by Italy. As one exasperated Slav complained, “[T]here is no doubt that such [an] outcome is all [the] work of Mr. Lloyd George… We have been treated as enemies – pure and simple. No enemy country has been robbed of such [a] proportion of its people…”[40] They were saved by Wilson. Even if the Europeans thought they could make a settlement without the Americans, they could not make one stick that was directly opposed by Washington. In his Memorandum of 10 February 1920, Wilson assailed the attempt to force Yugoslavia “to submit to material injustice by threats of still greater calamities in default of submission…” He denounced the proposal to give Italy the coastal strip and her “unjust and inexpedient annexation of all of Istria [which was] admittedly inhabited by Jugo-Slavs”. The provision regarding Fiume’s diplomatic representation “opens the way for Italian control of Fiume’s foreign affairs… and, taken in conjunction with the extension of Italian territory to the gates of Fiume, paves the way for possible future annexation of the port by Italy…” Wilson referred to “justice” 25 times, as the man once (on first arriving in Europe) likened to Jesus accused Lloyd George and Clemenceau of something like sinfulness. He envisaged far-reaching repercussions:

It is a time to speak with the utmost frankness. The Adriatic issue as it now presents itself raises the fundamental question as to whether the American Government can on any terms co-operate with its European associates in the great work of maintaining the peace of the world by removing the primary causes of war… [If] the old order of things which brought so many evils on the world is still to prevail, then the time is not yet come when this Government can enter a concert of Powers, the very existence of which must depend upon a new spirit and a new order…

Wilson finished with a warning that he would have to consider “the withdrawal of the treaty with Germany,” then before the Senate, “and permitting the terms of the European settlement to be independently established and enforced” by the American and other governments.[41] These words heralded America’s retreat from the peace settlement and recourse to isolationism.

Wilson subsequently said he would accept an agreement made, through direct negotiation, between Italy and Yugoslavia, and Lloyd George and Millerand (the new French Premier) concurred. As Temperley put it, “the two principals [Italy and Yugoslavia] were at last left to work out their own salvation.”[42] The peacemakers had failed.

The North

Much better progress was made in relation to Yugoslavia’s northern frontiers with Austria and Hungary, although every interested party was destined to be disappointed and aggrieved. The northern borderlands had very mixed populations, of Germans, Hungarians, Croats and Slovenes (all of them former enemies of the peacemakers), as well as Serbs (and Romanians and a few Italians), which made almost all territorial issues complex and controversial. As in the Adriatic, the principal difficulty was the persistent opposition to Yugoslavia of the Italians.

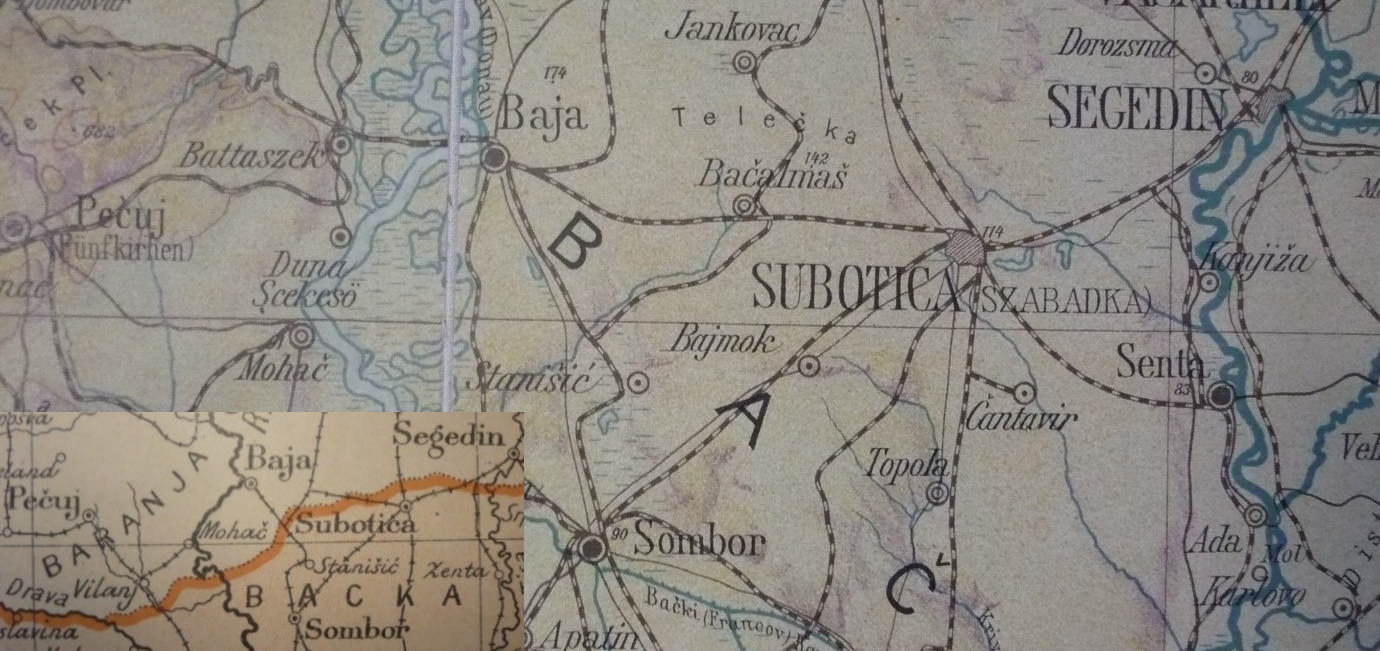

The Serbs did markedly better than their fellow-Slavs, the Croats and Slovenes. Yugoslavia received the western third of the Banat, where the Serbs had a majority and the Romanian claim was therefore rejected; the Commission on Romanian Affairs recognised “the secular aspirations of the highly-developed Yugoslav populations inhabiting the south-western portion of the Banat and closely connected with Belgrade”.[44] The new state also gained four-fifths of the Bačka, which had only 246,453 Slavs alongside 352,539 Magyars and 190,278 Germans.[45] The border was pushed far enough north to include the town of Szabadka (Subotica) and the Zombor-Szabadka railway line (see map), consigning thousands of Magyars and Germans to Yugoslavia. To the Italian objection that Zombor was surrounded by Magyar-majority countryside, Jules Laroche simply replied that the view of “une ville alliée” (Serbian Zombor) must prevail over that of “une compagne ennemi”.[46]

Regarding the Baranja, where again the issue was the frontier between Yugoslavia and Hungary, the Yugoslavs were to be disappointed. The Commission accepted figures which gave 36,132 Slavs (Serbs and Croats), 84,169 Germans and 173,417 Magyars.[47] Although the Yugoslavs claimed all of the Baranja, including the part north of the Drava river centred on the historic Magyar city of Pécs, the Americans and British insisted that the Slavs were “negligible minorities” in all but “isolated areas” north of the Drava – the Commission’s final report spoke of “une faible minorité” of Slavs – which was also “the obvious geographical boundary & the political frontier between Hungary & Croatia”. Yugoslavia would be given the area south of the river, where the Slavs probably had a majority, but most of the Baranja was to remain in Hungary.[48] To the west, Prekomurje and Medmurje were taken from Hungary and put into Yugoslavia. Both areas had Slovene majorities, but they lay north of the Drava and northern Prekomurje was ethnically mixed, with many Magyars as well as Slovenes. Ivan Žolger, the leading Slovene on the delegation, claimed that not getting Prekomurje would mean the loss of 100,000 Slovenes and, pressed by British, French and Yugoslavs, the Americans finally agreed in May to the cession of Prekomurje.[49]

Further west, in Lower Styria and Carinthia, where the frontier between Yugoslavia and Austria had to be defined, the Yugoslavs claimed “certain areas in which the Slovenes were not a majority” in order to counter the impact of “forced germanisation”. “Wherever it was possible to show that 50 years previously the Slovenes had been in possession,” Žolger told the Council on 18 February, “they should have ownership restored to them.”[50] The Italians had other priorities. Giving Drauburg (Dravograd) to Yugoslavia, they objected, would jeopardise the rail link between Italy and Hungary; the other members of the Commission asked why, by leaving Drauburg with Austria, the Italians sought a connection with Hungary through Austrian “c’est-à-dire ennemi” territory “plutôt que par territoire yougo-slav, c’est-à-dire ami” (Le Rond).[51] When the same issue (the railway line to Hungary) arose in relation to Marburg, Italy’s de Martino offered a revealing explanation:

It has been asked why Italy prefers to have communications across an enemy country [Austria] rather than across an allied country like Yugoslavia. One must hope that cordial relations will be established in the future between Italy and Yugoslavia, but … experience shows that the Yugoslavs put into their relations with their neighbours, when they are not cordial, a bitterness, not to say bad faith, so that all the guarantees one could foresee would not provide certainty that Italian traffic might not be disturbed at any given moment.[52]

According to Temperley, who went to Marburg in early April, “The situation here has always been odd – the town itself almost wholly German, the surroundings almost wholly Slovene, the problem of ultimate destiny very difficult to solve.” His idea of a solution – “we shall not concern ourselves to preserve to the Germans a corridor of territory running into the heart of Slovenia merely to satisfy a pedantic zeal for ethnological rectitude… We go on the principle of supporting our friends, and giving our enemies nothing more than what is necessary to prevent hardship” – would have seemed familiar to the British and French in Paris.[54] The Americans set aside their reservations, and Italy’s objection to the transfer of Marburg (and Drauburg) was overridden.

Klagenfurt

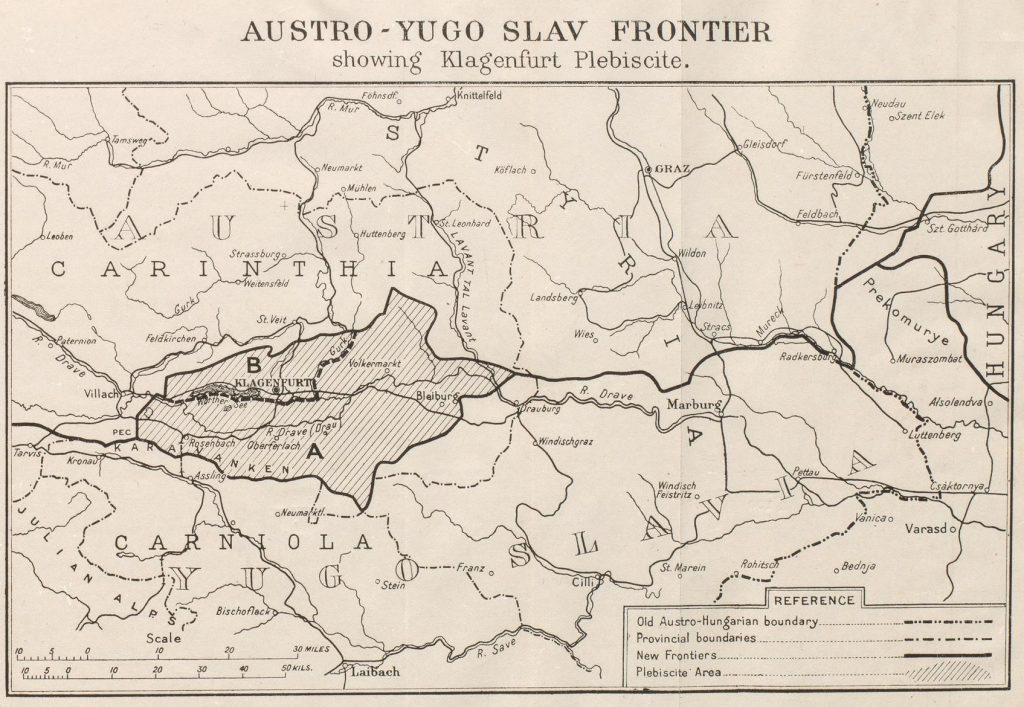

Klagenfurt, the capital of Carinthia, lay to the north of the Alpine spur, the Karawanken mountains, which ensured that the city’s economic ties were with Austria, and these mountains would have given Yugoslavia and Austria a natural frontier. In addition, it was believed that the vast majority of inhabitants (of the city and the wider area, the Klagenfurt Basin) were either Austrian-Germans or Wendes and that the latter, though a sub-group of the Slovenes, wished to remain part of Austria. The American officers who surveyed opinion in February 1919 were struck by “the large number of Slovenes who avowedly prefer Austrian rule” and one commented that, “The Slovene who does not want to be a Jugo-Slav is a curiosity we should never have believed in had we not seen him, and in large numbers.”[55] The French, British and Americans agreed to hold “an inquiry or consultation” to determine the “real feelings” of the Wendes.[56] This was the origin of the Klagenfurt plebiscite, the Council accepting the principle of a plebiscite on 12 May.

Yugoslav, especially Slovene, nervousness about the outlook was demonstrated when Žolger called this “the most horrible” moment “in the existence of my people” and submitted a paper entitled “The ruin of the Slovene Nation”.[57] Thinking it “better to secure half than to risk losing all” (Žolger), the Yugoslavs proposed to partition the Basin, giving Yugoslavia the southern and eastern part, where the census of 1910 had found 60,000 Slovenes and 25,000 Germans, and renouncing the north and west, including the city of Klagenfurt, to Austria.[58] This was rejected when the Council decided on 29 May to hold a plebiscite, but Wilson then agreed, offering a glimmer of hope to the Yugoslavs, to hold two plebiscites, one in the predominantly Slovene south and one in the German north (including the city).[59] In the Council on 4 June, Wilson, backed by Lloyd George, announced that the larger, Slovene part (designated Zone A) should vote separately(and first) on its future; the inhabitants of the more German Zone B would vote only if Zone A opted for Yugoslavia. Uniquely in the Balkans, the people of the area would be permitted to decide their own fate.

Still further west, the Assling Triangle was an important rail hub through which the Tauer-Bahn line ran from Trieste to Villach and Vienna. The area was heavily Slav (with 18,000 Slovenes and 1,500 Germans) and the Americans wanted to give it to Yugoslavia, with Tarvis in the west going to Italy (“There is not a single Italian civilian in Tarvis – but no matter”[60]) and Villach remaining Austrian. But Sonnino called for Assling’s retention by Austria, anxious as he was that the Trieste-Vienna railway line should not go through Yugoslav territory. In the Commission, de Martino for Italy described the need to keep the rail line from Yugoslavia “in case of war” with Italy and was accused of “favouring the enemy [Austria] at the expense” of an ally.[61] Temperley came up with a proposal to draw a line along the crest of the Karawanken, to a point north-west of Tarvis, and to allocate the area north of this line to Austria, “but not to adjudicate whether the [Assling] triangle at present or Tarvis” – in other words, the lands south of his line – “was either Jugoslav or Italian”.[62] This was agreed in May 1919 and the Italians conceded the southern part to Yugoslavia (with Italy gaining Tarvis) during the Adriatic negotiations of July-September 1919.

The Yugoslavs continued to make territorial demands during the autumn, trying to eat away at the fringes of Hungary, to no avail; Allen Leeper’s role in fending off these claims is described in ‘Leeper and Yugoslavia’. Yugoslavia’s loss of Klagenfurt was confirmed by the plebiscite held on 10 October 1920. Economic self-interest, decades of Germanisation and the influence of the Catholic priests combined to disappoint Yugoslav hopes.[63] The southern Slovene-majority Zone A voted 22,025 to 15,279 to remain part of Austria; this meant that “some 10,000 Slovenes must have voted for Austria”.[64] No plebiscite was required, then, in the northern zone and the whole Basin stayed with Austria.[65] This was a devastating blow, especially for the Slovenes.

Defeat

Worse was to follow: shortly afterwards, the Adriatic question ended in surrender and outright defeat for Yugoslavia. The failure of the peacemakers in January-February 1920 left the Yugoslavs exposed to the reality of Italy’s superior power and the reluctance of the Western powers to intervene in the seemingly unsolvable dispute. The Italian army continued to occupy most of the disputed territory and d’Annunzio remained master of Fiume. Direct negotiations between the Yugoslavs and Italians took place intermittently for almost ten months, beginning in London and Paris in February 1920 and ending at Santa Margherita near Rapallo in November. During this time, the tides of fortune ebbed away from Yugoslavia. America’s involvement in European affairs virtually ceased and this was confirmed when Wilson decided not to contest the election of November 1920 and the Republicans came to power. In relation to the Adriatic question, Lloyd George commended the “moderate” stance of Italy and believed that “if pressure is put upon both sides to settle, we might get a final solution,” and the British and French told the Yugoslavs that they had no prospect of gaining their support if talks failed.[66]

Faced by a stronger opponent, the Yugoslavs accepted a crushingly disappointing settlement in the Treaty of Rapallo of 12 November 1920. The new frontier was placed on the watershed of the Julian Alps, slightly east even of the Treaty of London line (not to mention the Wilson Line), giving Italy all of Istria, Idria and Adelsburg to the north, and Monte Nevoso in the east. Monte Nevoso was the key to defending Istria and Trieste – it was considered as vital to Italy’s defence against the “military menace” of Yugoslavia as the Brenner Pass was against “the German menace” to the north[67] – but it had received barely a mention during the discussions of 1919 because its place in Yugoslavia (or a free state) seemed assured. Fiume (not including Sušak, which went to Yugoslavia) was to be an independent state, which meant it would be governed by its Italians, and the coastal strip between Fiume and Istria was to be part of that state. Zara, which in 1919 seemed destined to be an independent city-state, went to Italy, as did the islands of Cherso, Lussin, Pelagosa and Lagosta. Yugoslavia acquired the rest of Dalmatia and, in the north, Assling.

Leeper called Rapallo “complete capitulation” and noted one Yugoslav’s conviction that “the Yugoslavs wd work for a revision of it, by war if necessary, in some years’ time”.[69] Nicolson’s feelings were clear when, considering an Albanian complaint about Serbian misconduct, he commented that, “We are always nagging at the S.C.S. Govt. for one cause or another, & have never really helped them when they were in the right as in the Adriatic Question.”[70] Wilson’s deep disappointment was expressed in unpresidential language:

I have been rendered very sad by what I have read in the papers about the alleged Jugo-Slav-Italian settlement. Italy has absolutely no bowels and is evidently planning a new Alsace-Lorraine on the other side of the Adriatic which is sure to contain the seeds of another European war. If it does, and the seeds develop, personally I shall hope that Italy will get the stuffing licked out of her. She has absolutely no conscience in these matters. Of course, however, if the Jugo-Slavs have entered into an agreement voluntarily with the Italian Government and wish it to stand as a settlement, I do not feel that we are obliged to defend them against themselves.[71]

D’Annunzio’s removal from Fiume soon followed. The city was economically and financially ruined and law and order had collapsed. On 24 December 1920, the Italian army began to move in and there were three days of low-intensity fighting. D’Annunzio’s palace was shelled and the poet-condottiere (the “Man of Victory”) decided to leave, finally departing on 18 January (“I leave to Fiume my dead, my sorrow, and my victory”).[72] Mussolini’s seizure of power in Italy in October 1922 led to renewed negotiations about Fiume with Yugoslavia, during which his attack on Corfu (Greece) in August 1923 showed how a Fascist power might deal with opposition from a weaker neighbour. The Treaty of Rome of January 1924 brought the inevitable, Italy’s acquisition of Fiume and the coastal strip. In one sense, it was an empty triumph, for the Yugoslavs looked to other outlets – the port at Sušak was developed, a new railway line from Zagreb to Split opened in 1925, and Yugoslav goods reached the Aegean through Salonica (Thessaloniki) in Greece – and Italy did nothing to develop Fiume: “economically it had been killed”.[73]

About 231,000 Romanians, 472,000 Magyars and over half a million Germans were brought into Yugoslavia, most of them in the Bačka, the Baranja and the Banat. However, the settlement left about 720,000 Slavs outside Yugoslavia, over half a million in Italy alone (with only 12,553 Italians consigned to Yugoslavia). Most of the ‘lost’ Slavs were Slovenes, and many were Croats, but very few were Serbs, feeding the impression that Paşić and Milenko Vesnić (another Serb) had fought harder for Serbian claims and sacrificed Croats and Slovenes (causing Anton Korošec, the Slovene leader, to refuse to sign the Treaty of Rapallo).[74] So, what happened at Paris and Rapallo got the new state off to a disastrous start. A state which, more than most, needed a nation-building experience fell prey, instead, to recrimination and division.

Pointing accusatory fingers at Paşić and Vesnić rather lets the Allied statesmen off the hook. Lloyd George felt that Wilson, by wrecking his January Compromise, had “mismanaged the Fiume negotiation”. For Nicolson, though Wilson managed to “maintain his principles intact”, his failure to overcome the Italians filled his admirers with “blank despair” and “convinced us that Woodrow Wilson was not a great or potent man”. Arthur Walworth, the historian, was similarly critical of the “covenanter’s devotion to a political creed” and accused the “moralizing Americans” of “maladroit interference” in “this essentially European controversy”.[75] The Prophet of the White House was judged by a higher standard, and deemed less effective, than an operator like Lloyd George. But Lloyd George and Clemenceau, whose pragmatic disposition to compromise (or deplorable lack of principle) can only have encouraged Italian stubbornness, surely deserve at least equal billing as the authors of failure. The Yugoslavs, largely passive, were not authors of anything; almost like a defeated power, they were confined to pleading, worrying and waiting in vain.

[1] Stephen Bonsal, Suitors and Suppliants: The Little Nations at Versailles (New York, 1946), 100, 16 April 1919.

[2] The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was not renamed Yugoslavia until 1929. However, during the deliberations of 1919, the words “Yugoslav” and “Yugoslavia”, variously spelt, were used on almost every occasion. For brevity and convenience, this study will do the same.

[3] Bonsal, Suitors and Suppliants, 101, 23 April 1919.

[4] Foreign Office Papers, FO 608/15, 380, 396, Italo-Yugoslav Boundary, notes by Nicolson, 20 January 1919. See also Harold Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919 (London, 1933), 248, Diary, 24 January 1919.

[5] David Hunter Miller, My Diary at the Conference of Paris, With Documents privately printed, 1918, IV, 237-38, Outline of Tentative Report and Recommendations Prepared by the Intelligence Section, 21 January 1919.

[6] Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 264, 272, Diary, 18, 26 February 1919.

[7] FO 608/40, 309, Rodd to Curzon, 20 February 1919, specifying the claim to Trieste and Gorizia in particular.

[8] Hugh and Christopher Seton-Watson, The Making of a New Europe: R.W. Seton-Watson and the last years of Austria-Hungary (London, 1981), 360n59, Orlando’s comment to Malagodi on 19 February 1919.

[9] H.W.V. Temperley, ed., A History of the Peace Conference of Paris (London, 1921), IV, 289.

[10] FO 608/15, 365, Nicolson, The Question of Fiume, 15 January 1919. Nicolson’s paper reflected the views of Robert Seton-Watson. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 231, Diary, 11 January 1919.

[11] FO 608/8, 545, 554, The Future of the Port of Fiume (with maps), with notes by Leeper, Crowe and Hardinge, 31 March 1919.

[12] The best source for the split in the American camp is Charles Seymour, Letters from the Paris Peace Conference by Charles Seymour , edited by Harold B. Whiteman, Jr. (New Haven and London, 1965), 194, 202 et seq..

[13] Paul Mantoux, The Deliberations of the Council of Four (Princeton, 1992), I, 125-29, 3 April 1919.

[14] Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 182, 315, Diary, 23 April 1919.

[15] Papers of Frances Stevenson, FLS/4/11, 126, Diary, 6 May 1919. The pun was much favoured in France. ““Orlando is Fiuming again,” said the wags of Paris. “Le Président Wilson Fiume sa pipe avec un Trieste sourire.”” George Goldberg, The Peace to End Peace: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 (London, 1970), 200.

[16] Charles Seymour, ed., The Intimate Papers of Colonel House (London, 1926), IV, 483, House’s diary, 17 May 1919. Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States: The Paris Peace Conference 1919 (FRUS), V, 707-11, Council of Four, 19 May 1919. See also Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, II, 108-9, 19 May 1919. “Wilson permitted unlimited pressure on the Italians but none on the Yugoslavs” – House in T. G. Otte, ed., An Historian in Peace and War: The Diaries of Harold Temperley (Farnham and Burlington, 2014), 564, 8 January 1925.

[17] Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson (Princeton, 1989), Volume 59, 248, 255, Diaries of Grayson and Benham, 18, 19 May 1919.

[18] Ibid., Volume 60, 332, Diary of Dr Grayson, 10 June 1919.

[19] Lord Vansittart, The Mist Procession: The Autobiography of Lord Vansittart (London, 1958), 211. Edward James Woodhouse and Chase Going Woodhouse, Italy and the Jugoslavs (Boston, 1920), 292-94.

[20] Andrew Thorpe and Richard Toye, eds., Parliament and Politics in the Age of Asquith and Lloyd George: The Diaries of Cecil Harmsworth, MP, 1909-1922 (Cambridge, 2016),301, 21 November 1919.

[21] For Wilson’s giving up on the plebiscite, see Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 63, 424, Wilson to Polk, 21 September 1919. FO 608/41, 318-19, British Delegation Minute (Leeper), 11 October 1919, with Annex VII, Substance of telegram from President Wilson to Polk, dated 22 September 1919: communicated by Polk on 2 October 1919.

[22] Lucy Hughes-Hallett, The Pike: Gabriele D’Annunzio Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War (London, 2013), 478, quoting an American observer. See also Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 446, 8 July 1919.

[23] Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 63, 364-66, Polk to Wilson and Lansing, 17 September 1919, enclosing Tittoni’s appeal to Wilson on behalf of Italian Fiume

[24] Ibid., 464-65, Jay to Phillips, 23 September 1919, with Nitti’s message to Wilson.

[25] Ibid., 393, Phillips to Wilson, 18 September 1919, enclosing Clemenceau’s message to Wilson. FO 608/36, 332, note by Nicolson, 13 October 1919; FO 608/41, 11, 19, Rodd to Curzon, 29, 30 September 1919. Rodd, long considered pro-Italian, later “confessed” that he “could not help feeling a certain romantic sympathy” for d’Annunzio. Sir James Rennell Rodd, Social and Diplomatic Memories, 1902-1919 (London, 1925), 386.

[26] FRUS, VIII, 225-26, Heads of Delegations, 15 September 1919. FO 608/41, 46, Crowe to Curzon, 30 September 1919; ibid., 53, British Mission to Foreign Office, 19 September 1919.

[27] FO 608/28, 219, Imperiali to Hardinge, 27 October 1919.

[28] FO 608/28, 310, Memorandum on the position of the American Government, 27 October 1919. Charles Seymour, ‘The Struggle for the Adriatic’, The Yale Review, Volume IX, No. 3 (April 1920), 481 (“barren beach”).

[29] Lloyd George Papers, F/55/4/39, Nitti to Lloyd George, 27 October 1919.

[30] Ibid., F/55/4/40, Foreign Office to Buchanan, 31 October 1919, enclosing Lloyd George’s telegram to Nitti, 31 October 1919, copied to Washington; ibid., F/60/3/16, Lloyd George to Grey, 31 October 1919.

[31] Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question (Parliamentary Paper, London, 1920), 3-9. Temperley, History of the Peace Conference of Paris, IV, 311-15; V, 405-12.

[32] Isaiah Bowman in E.M. House and C. Seymour, eds., What Really Happened at Paris: The Story of the Peace Conference, 1918-1919 by American Delegates (London, 1921), 464, Bowman on 23 December 1920.

[33] Seymour, ‘The Struggle for the Adriatic’, The Yale Review, Volume IX, No. 3 (April 1920), 479-80.

[34] FO 608/44, 542, Crowe to Curzon, 19 December 1919. Trumbić, Yugoslavia’s Foreign Minister, was still in ignorance in the first week of January. Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/15/2, Lupis-Vukić to Seton-Watson, 7 January 1920.

[35] Henry Baerlein, The Birth of Yugoslavia (London, 1922), II, 213.

[36] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 12, 13, 14 January 1920. See also Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/15/2, Lupis-Vukić to Seton-Watson, 14 January 1920. Leeper’s important part in these talks is outlined in ‘Leeper and Yugoslavia’.

[37] Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question, 18, Revised Proposals (“the January Compromise”) of 14 January 1920.

[38] FRUS, IX, 860, International Council of Premiers, 12 January 1920.

[39] E.L. Woodward and Rohan Butler, eds., Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939 (London, 1956), First Series, Vol. II, 862-64, 876-82, Notes of Meetings of 13, 14 January 1920.

[40] Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/15/2, Lupis-Vukić to Seton-Watson, 14, 21 January 1920.

[41] Link, Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 64, 398-402, Lansing (for Wilson) to Wallace, 10 February 1920. Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question, 23-25. Temperley, History of the Peace Conference of Paris, IV, 321-24; V, 419-23. In fact, he threatened to withdraw both the Treaty of Versailles and the Insurance Treaty signed with France on 28 June. Wilson’s letter was delivered to the Conference on 14 February.

[42] Link, Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 65, 37-39, Polk to Wilson, 2 March 1920, enclosing draft reply (approved by Wilson) to Lloyd George and Millerand. Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question, 25-32. Temperley, History of the Peace Conference of Paris, IV, 327.

[43] Jevto Dedijer, Map of the Yougoslav Countries (Berne, 1919). Baerlein, The Birth of Yugoslavia, II, 418.

[44] Report by the Committee for the Study of Territorial Questions relating to Rumania and Yugoslavia: Rumanian Frontiers, FO 608/49, 76, 6 April 1919.

[45] Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 20 (Annexes), 236, Tableaux Statistiques – the population in the area claimed by Yugoslavia. The Commission based its estimates on the census of 1910.

[46] Ibid., Procès-Verbal No. 8, 71, 28 February 1919.

[47] Ibid., Procès-Verbal No. 20 (Annexes), 236, Tableaux Statistiques.

[48] FO 608/41, 453, note by Leeper, 22 March 1919. Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 17, 162-63, 18 March 1919; Report, 226-27, 6 April 1919. The Serbs knew Pécs as Pečuj.

[49] FO 608/41, 521, Žolger to the Peace Conference, 13 May 1919. Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 26, 305, 20 May 1919. Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 421, 20 May 1919.

[50] FRUS, IV, 49, Council of Ten, 18 February 1919.

[51] Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 15, 132-35, 136-37, 11 March 1919.

[52] Ibid., Procès-Verbal No. 16, 147, 13 March 1919. Instead of “bad faith”, Lederer translated “une mauvoise foi” as “treachery”. Ivo J. Lederer, Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference: A Study in Frontiermaking (New Haven and London, 1963), 177.

[53] Temperley, History of the Peace Conference of Paris, IV, 370.

[54] Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 393, 396-98, 4, 6 April 1919.

[55] FRUS, XII, 505, Miles and King to Coolidge, 9 February 1919.

[56] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 13 March 1919.

[57] FO 608/41, 521, Žolger to the Peace Conference, 13 May 1919.

[58] Ibid., 528, Leeper to Crowe, 15 May 1919 (Žolger). Trumbić claimed that there were 80,000 Slovenes and 5,000 Germans in the south and east. Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 25, 295-99, 20 May 1919.

[59] This change was essentially the work of the American geographer, Douglas Johnson. Link, Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 60, 121-22, Johnson to Wilson, 4 June 1919.

[60] Baerlein, The Birth of Yugoslavia, II, 374.

[61] Commission des Affaires Roumaines et Yougo-Slaves, FO 374/9, Procès-Verbal No. 21, 264-69, 9 May 1919. Otte, Diaries of Harold Temperley, 409, 9 (misdated 8) May 1919.

[62] Ibid., 411-13, 10 May 1919.

[63] Baerlein, The Birth of Yugoslavia, II, 375-83.

[64] H.C. Darby and R.W. Seton-Watson, ‘The Formation of the Yugoslav State’, in Stephen Clissold, ed., A Short History of Yugoslavia (Cambridge, 1968), 168.

[65] A Communist-era history attributed the vote to the combined influence of the Catholic Church and those Slovene Social Democrats who argued that “the Slovene proletariat” would do better under Socialist Vienna than conservative Belgrade. Vladimir Dedijer et al, History of Yugoslavia (New York, 1974; originally Belgrade, 1972), 507. It has been suggested that women voters anxious to see their children avoid compulsory service in the Yugoslav army favoured Austria, where there was no conscription. Margaret MacMillan, Peacemakers: The Paris Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War (London, 2001), 263.

[66] Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 66, 45, Lloyd George to Wilson, 5 August 1920. David Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties (London, 1938), II, 896-97. House and Seymour, What Really Happened at Paris, 138. Dennison I. Rusinow, Italy’s Austrian Heritage 1919-1946 (Oxford, 1969), 143-46.

[67] Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 178-79.

[68] Clissold, A Short History of Yugoslavia, 167.

[69] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 15 November 1920.

[70] FO 371/4689, 238, note by Nicolson, 12 December 1920. See also Baerlein, The Birth of Yugoslavia, II, 232-37, 384-85 (Istria was “a new Alsace”). Seton-Watson praised the “statesmanship” of Italy’s renunciation of Dalmatia and decreed that “any settlement is better than none”. Hugh and Christopher Seton-Watson, The Making of a New Europe: R.W. Seton-Watson and the last years of Austria-Hungary (London, 1981), 416n64.

[71] Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 66, 367, Wilson to Colby, 15 November 1920.

[72] Hughes-Hallett, The Pike, 556-68. Baerlein, The Birth of Yugoslavia, II, 216-20. Temperley, History of the Peace Conference of Paris, IV, 335.

[73] René Albrecht-Carrié, Italy at the Paris Peace Conference (New York, 1938), 309n61. Huey Louis Kostanick, ‘The Geopolitics of the Balkans’, in Charles and Barbara Jelavich, eds., The Balkans in Transition: Essays on the Development of Balkan Life and Politics since the Eighteenth Century (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1963), 21.

[74] Lederer, Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference, 297.

[75] Hankey Papers, 1/5, Diary, 15 February 1920. Lord Riddell, Intimate Diary of the Peace Conference and After, 1919-1923 (London, 1933), 180, 27 March 1920. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 184, 209. Arthur Walworth, Wilson and his Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 (New York and London, 1986), 552-53.