Welcome

One of the Foundling Hospital’s close neighbours in Bloomsbury was the Hospital for Sick Children, known today as Great Ormond Street Hospital. The latter’s original home, the first building to be converted, was 49 Great Ormond Street, a stone’s throw from the Foundling Hospital Estate and the home a century earlier of Dr Richard Mead, royal physician, one of the founders and first governors of the Foundling Hospital in 1739. This was a coincidence and there was no intimate connection between the two institutions. In fact, the Foundling Hospital attempted in 1851 to prevent the establishment of the new children’s hospital in Great Ormond Street, and the site was not sold to its neighbour when the Foundling Hospital moved out of London in 1926. These are not decisions of which the Foundling’s admirers and heirs can feel enormously proud, even if they were made for very good and defensible, even compelling reasons.[1]

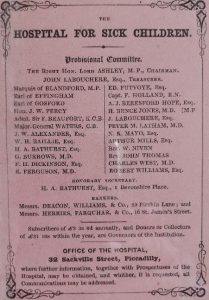

Great Ormond Street Hospital is one of London’s most venerable institutions and Dr Charles West (1816-98) is celebrated as its principal founder. Having worked in a children’s hospital in Paris, West came to the view that British hospitals, which often accommodated adults and children together in the same wards, catered inadequately to the particular needs of sick children. He urged the creation of a London children’s hospital in the 1840s and finally, on 30 January 1850, a Provisional Committee to establish such an institution was formed: a ‘meeting of Gentlemen’, including West, formed this committee, its stated aim was a hospital with 100 beds for children aged 2 to 12, and an appeal for funds (a Collector’s Card is shown here, right) was published in the press in February 1850.[2]

Great Ormond Street Hospital is one of London’s most venerable institutions and Dr Charles West (1816-98) is celebrated as its principal founder. Having worked in a children’s hospital in Paris, West came to the view that British hospitals, which often accommodated adults and children together in the same wards, catered inadequately to the particular needs of sick children. He urged the creation of a London children’s hospital in the 1840s and finally, on 30 January 1850, a Provisional Committee to establish such an institution was formed: a ‘meeting of Gentlemen’, including West, formed this committee, its stated aim was a hospital with 100 beds for children aged 2 to 12, and an appeal for funds (a Collector’s Card is shown here, right) was published in the press in February 1850.[2]

Over a year later, on 18 March 1851, a public meeting to raise support for the project was held at the Hanover Square Rooms in Mayfair. A ‘subcommittee for finding suitable premises’ got down to work and the Honourable Secretary, Henry Bathurst, was instructed ‘to advertise for premises … within 3 miles West & North West of Charing Cross’.[3] Various sites were considered, including the old Consumptive Hospital at Chelsea, before the house at 49 Great Ormond Street (left) emerged on 1 April 1851 as the favoured option.[4] The owner, a Mr Martelli, was averse to cancelling the lease of the existing tenant if he could not secure a rent of £200 a year, so, on 29 April, the Provisional Committee decided to take the house for ‘£200 per annum, for a period of 21 years’.[5] There is no indication in the formal minutes that anyone was aware of the connection to Richard Mead. On 3 June, to distinguish it from the Infirmary for Children in Lambeth, the name, ‘The London Hospital for Sick Children’, was adopted.[6]

The body that would have to license the new hospital was the General Board of Health. Working with local health boards and town councils, it was responsible under the Public Health Act of 1848 for countering potential threats to health, dealing with drainage, water supply, cemeteries and the “offensive state” of some toilets and lodging houses. The three active members (Commissioners) were the Earl of Shaftesbury (Viscount Ashley MP until 2 June 1851), Edwin Chadwick and Dr Southwood Smith; the nominal President, Lord Seymour, rarely attended.[7] The Board’s first communications regarding the new hospital came not from the Provisional Committee but from opponents of the project. On 17 June, Mr A. Holmstead of Ormond Club House wrote ‘complaining of the proposed use of a house in Great Ormond Street as a Hospital for sick children’ and on 21 June the Clerk to the Guardians of the Holborn Poor Law Union complained of ‘the injurious effects likely to be produced to the Union by the establishment of a Hospital for Sick Children in Powis Place’ (the street abutting onto Great Ormond Street). The Board duly ordered,

That the attention of the Secretary of the Society which is founding the Hospital be called to the 8th Section of the Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act [of 1848], which prohibits the building or opening of any Hospital for the reception of patients afflicted with contagious or infectious disorders without the approval in writing of the General Board of Health.

Mr James of the Holborn Union was assured that ‘the whole question referred to in the letter will be carefully considered by the Inspector employed by the Board to inquire into the subject before the Board give their consent to the opening of the Hospital’.[8] The letters from Holmstead and James were sent to Shaftesbury as chairman (de facto) of the Board of Health, but another letter was apparently addressed to Shaftesbury in his capacity of chairman of the Provisional Committee and was noticed by that body on 24 June:

The Hon[orary] Sec[retary] was … directed to acknowledge a letter addressed by Mr Sibley to Lord Shaftesbury and to assure him that it was not the intention of the Committee to take in any cases of small pox and that it was not the principal object of the Hospital to receive patients suffering from infectious diseases of any kind.[9]

So, it was a wave of local protest that the Foundling Hospital joined at the end of June. No less a person than Lord Chief Baron Sir Frederick Pollock wrote to the Foundling’s Treasurer, George Baker, drawing his attention to ‘a report which is current in the neighbourhood that it is intended to open a Hospital for the reception of children with infectious diseases in Great Ormond Street immediately adjoining the estate of this charity’.[10] The General Committee despatched Secretary John Brownlow and two other officers, Richard Vanheythuysen (the Hospital’s solicitor) and Henry Curry, to visit the site of the projected hospital and on 27 June these officers reported that ‘we find the premises in every respect suitable for such a purpose’ and that it was ‘impossible for us to say whether the occupation of the house for the proposed purpose will be a nuisance to the Foundling Estate until it is occupied’. They were assured that the reported intention to use the attached stable partly to receive out-patients and partly as ‘a Dead House’ (mortuary) was untrue, ‘the Stable is to be let only as a Stable. If this should prove to be the truth of the case we think no nuisance is likely to arise to the Inhabitants of the Foundling Estate except such as may be occasioned by the use of the Garden behind the house as a play-ground for convalescent children.’[11]

This report did not engage with the perceived danger of bringing children with infectious diseases into the neighbourhood, and it may be that Brownlow and his colleagues received the sort of ‘not the principal object’ assurance noticed above. It is probably fair to say that this assurance was accurate (not the principal object) but disingenuous, for the treatment of children with infectious diseases was fully intended. At the public meeting in March, Dr George Burrows of the Provisional Committee said that, ‘Many of the infantile disorders were diseases that spread rapidly by infection or contagion’ and that, as a result, an infected child ‘should be removed from the domestic circle… When a child was attacked with scarlet fever or measles the disease soon spread to the other members of the family’ and then to others; removal of such a child to a hospital would protect ‘not only the other children of the family, but the children of an extensive locality (hear, hear)’.[12] The Board of Health’s intervention presupposed the intention to receive ‘patients afflicted with contagious or infectious disorders’ and the Official Sanction that the Board issued in January 1852 duly approved the creation of a children’s hospital ‘which may receive [among others] patients afflicted with contagious or infectious diseases or disorders’.[13]

With their report, Vanheythuysen and Curry also submitted ‘a copy of a Memorial which has been presented to the Board of Health, by the Landowners, Occupiers and authorities of the parish’.[14] Unfortunately, this Memorial is not extant, but the nature of the General Committee’s objection to the proposed children’s hospital, rejecting the advice of its own officers, suggests that it may have centred on the infectious-diseases issue. Following the report, the Committee’s Minutes continued,

Read also the Memorial referred to in the said report.

Resolved,

That this Committee has heard with considerable alarm that it is proposed to open one of the large houses in Great Ormond Street, which immediately adjoins the property of this Charity, as a Hospital for sick children.

That the concentration into one focus of diseases incidental to children, infectious and otherwise, in such a situation is likely to prejudice the health of the neighbourhood, and that of the inmates of this hitherto healthy Establishment, consisting of more than 400 individuals.

That should such a Hospital be permitted to be opened, the interests of this Corporation in the numerous houses in the vicinity will be greatly depreciated in value by reason of the present occupiers leaving the neighbourhood.

Ordered,

That a copy of the above resolutions be sent to the Board of Health with an earnest appeal that they will be pleased to exercise the powers vested in them by preventing the occupation of the house in question for the purpose of a Hospital for sick children.[15]

So, it was feared that the new hospital might ‘prejudice the health’ of the 400-odd foundling children. This fear is understandable. The mortality rate at the Foundling Hospital was extremely high in the early decades of its existence, inoculation against smallpox was introduced, and the medical examination of every new entrant was designed to exclude any child with an infectious disease. The era of the General Reception (1756-60), when a Parliamentary grant was conditional on the acceptance of every offered child, was remembered as a truly disastrous time in the Hospital’s history: infection was rampant and the mortality rate soared to 70%, and Secretary John Brownlow was later to write that the Foundling became ‘a charnel-house for the dead’.[16] In addition, and more acutely, everyone in London was still in a state of alarm and apprehension as a result of the cholera epidemic of 1848-49, when thousands perished in Britain’s cities and 2,298 died in London in one week in September 1849. This was at a time when most believed that cholera was carried in ‘bad air’ (‘the miasma theory’), John Snow not showing until the mid-1850s that it was water-borne. It was impossible in London in 1851 not to be terrified by the prospect of having victims of disease brought into one’s neighbourhood. The Committee’s concern that the arrival of the new hospital would depress the Foundling’s rental income – the Foundling Hospital Estate, consisting of hundreds of residential and commercial properties, extended to the south side of Guilford Street, just north of Great Ormond Street – seems a less defensible line of argument, but the Foundling Hospital did depend on this rental income for its very existence.

Although it begs questions as to the true opinion of John Brownlow, a letter in the Secretary’s Letterbook sheds light on the wave of panic caused by the new-hospital proposal. On 19 June, Brownlow wrote to one of the executors of a house, apparently not no. 49, to warn ‘that this neighbourhood is in commotion at the idea of your letting Mr. Turner’s House in Great Ormond St. as a Hospital for Diseased Children’. Given the rumour that ‘the Stabling at the back on this estate’ was intended to be used ‘as a means of access’ for patients, ‘it would be desirable that the Governors of this House should receive some communication on the Subject as some of their tenants are already frightened out of their lives.’[17] This phrase does not leave much room for doubt regarding the nature and intensity of popular sentiment. The Hospital’s sensitivity to public health concerns was also demonstrated by an episode which, though having nothing to do with Great Ormond Street, may have had some relevance because of its timing. On 3 July 1851, Brownlow wrote of a complaint that neighbouring premises were being ‘used by a cheap undertaker as a depôt for dead bodies from Hospitals &c’ and stated that ‘I need not point out the obvious objections to this disgusting mode of occupying the premises’. He followed this with a letter to the Board of Health:

I feel it my duty to apprize you that a nuisance has lately arisen in this neighbourhood which seems to require the interference of the General Board of Health.

No. 2 Hunter Mews, Henrietta Street, Brunswick Square is reported to be occupied by some inferior Undertaker as a depôt for dead bodies until it suits him to bury them. The people in the neighbourhood are naturally alarmed at this proceeding and have made their complaint to me.

May I hope should this nuisance be removable by the Board of Health, that you will interfere in the matter.[18]

The Board of Health sent Secretary Bathurst a letter calling his attention to the provisions of Section 8 of the Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act, and Bathurst gave notice under the Act of the intention to open a hospital and offered ‘on the part of the Hospital Committee to meet any persons appointed by the Board to inspect the premises’. Henry Austin, the Board’s Secretary, and a colleague (Dr R.D. Grainger, one of the Board’s Medical Inspectors) were ‘requested to fix some day for inspecting the premises in question’.[19] Dr West and some colleagues received Austin and Grainger at Great Ormond Street in the first week of July, when, West believed, ‘the opinion of these gentlemen seemed generally favourable’. The inspectors promised to let the Provisional Committee know ‘in a week or ten days’ of any alterations required to the building, ‘it being understood that the Board of Health will officially sanction the opening of the house as a Hospital if such suggestions are complied with by the Committee’.[20] On 13 July, the Committee was told of the conditional acceptance of its application:

The Hon. Sec. read a copy of the report made by Mr Grainger & Mr Austin to the Board of Health, and also a letter from the Secretary to the Board officially announcing that on compliance with the conditions recommended in such report the Board would be prepared to sanction the opening of the Hospital in Gt. Ormond St.. The Committee having taken the matter into consideration determined to adopt the recommendations of the Board of Health, and appointed a Sub Committee … to superintend the plans for carrying out such recommendations with the view to the same being done in the most economical manner.[21]

Construction delays followed and there were financial concerns: ‘the expense of effecting the alterations needed in the house in Gt. Ormond St. including the construction of the Dead House on its altered site and the other recommendations of the Board of Health would amount to £650’ and ‘the expense of the necessary outfit for opening the Hospital with 20 beds and for opening a Dispensary would amount to about £300’ – and provision had to be made for the future operating costs of the hospital – so the Committee resolved on 7 November that ‘the Hospital should open with 20 beds in the General wards and with 8 beds in the fever wards on the understanding that the number of Patients in the two classes of wards should not exceed 20 at one time’.[22]

Finally, on 8 January 1852, the Board of Health considered ‘a letter from Mr. Bathurst, acquainting the Board that the necessary alteration [sic] had been made in the premises in Great Ormond Street proposed to be used as a Hospital for Children, and requesting a further inspection’. Austin and Grainger made ‘the required examination’ and on 20 January recommended ‘that the sanction of the Board be given’; the following day, the Board sent its ‘Official Sanction’ of the new ‘Hospital for Sick Children’.[23] The hospital opened on 16 February 1852, beginning with only ten beds. During the previous week, it was ‘open on view between 12 & 4 every day’ and Charles West made a point of inviting John Brownlow to ‘look at it. I should feel great pleasure in meeting you and going over it with you… The house, however, will be open all day to you, if you call at any hour & mention your name.’[24]

The role of the Earl of Shaftesbury, the great social reformer, in the success of the project, in particular in securing the approval of the Board of Health, must be considered rather anomalous. Viscount Ashley (as Shaftesbury was known until June 1851) became the nominal (non-attending) chairman of the Provisional Committee in February 1850. He chaired the public meeting of the projected hospital’s supporters on 18 March 1851 and gave the keynote speech, in which he was keen to show how the children’s hospital might be an invaluable piece of a larger jigsaw:

The mortality among children in the metropolis was not to be traced only to the peculiarity of their diseases, but also owing to the sanitary conditions of the localities in which they lived… If they could bring to bear great sanitary measures over the length and breadth of this great metropolis, and over our great towns, they would lessen that mortality, though they could not altogether supersede the necessity for an institution such as that it was now proposed to establish [hear]. Let them have the institution to cure the diseases that were incident to children, but let them also introduce those sanitary measures that frequently would make its assistance unnecessary [hear, hear].[25]

For Shaftesbury, the work of the new hospital would complement that of the Board of Health, which in itself had a limited capacity to effect change.[26] He made no attempt to stand down from his Board of Health role when it examined the hospital’s application. He attended (and chaired) the Board when the first objections (addressed to him) were received in June 1851 and when the hospital’s application was delivered and Austin and Grainger were appointed to inspect the premises, but he was away touring his newly inherited estates when the Board gave its Official Sanction in January 1852. His undeclared involvement on both sides of the fence, and failure to recuse himself, would certainly be considered inappropriate today, but it passed unnoticed in that less rule-bound and bureaucratic age.

Over the following decades, the Foundling Hospital and Great Ormond Street (the future name) coexisted without apparent difficulty, and the latter’s archives include the programme of a concert at the Foundling to raise funds towards ‘the Completion of the Hospital for Sick Children’ in 1887.[27] However, few of the Foundling children were brought to Great Ormond Street. The medical care in their own ‘hospital’ was of such a high standard, and had been since the days of Richard Mead, that the foundlings did not need the new hospital for most types of treatment. Many others did, of course: Great Ormond Street grew rapidly, treating about 700 in-patients (and over 12,000 out-patients) per annum by the 1870s, and over 2,000 in- and 25,000 out-patients in 1900, perhaps justifying Alec Forshaw’s verdict that, ‘The Foundling Hospital was increasingly overshadowed by the Children’s Hospital in Great Ormond Street.’[28] This is debatable, given that the Foundling accommodated up to 400 children, but one can certainly say that Bloomsbury had become home to two of London’s great children’s charities.

Farewell

In the 1920s, by which time Great Ormond Street and the properties into which it had expanded were outdated and constricting, the hospital’s leaders contemplated reconstruction or even removal to new premises. At the same time, the Foundling Hospital’s governors were anxious to leave Bloomsbury, which was now crowded and polluted, and to move to a green-fields site outside London. This coincidence meant that Great Ormond Street might have acquired the site of the Foundling Hospital, but that neat solution proved unattainable.

- Reconstruction of the Hospital, and

(a) Acquisition of Timber Yard.

(b) Acquisition of houses in Guilford Street.

5. The question of the advisability of acquiring part of the Foundling Hospital site for the erection

of a model Children’s Hospital.

6. County Recovery Hospital.[36]

The Board of Management, also in October, discussed ‘the question of the rebuilding of the Hospital on the Site of the Foundling Hospital’, the Reconstruction Sub-Committee and the Medical Committee resolved in December that ‘every effort’ should be made ‘to obtain the Foundling Hospital Site’ and one Board member ‘reported his negotiations with the new owners’.[37]

The new owners were Foundling Estates Limited, the syndicate established by White in May 1925, hereafter called FEL. The Board of Management secured FEL’s agreement to sell the freehold on the timber yard, 13 houses on Guilford Street (nos. 34-46), and Grenville Mews (property, south of 47-50 Guilford Street, on which Great Ormond Street had held a 999-year lease from 1915), which transactions were completed in March 1927 – see E in the hospital plan that was printed in subsequent annual reports – but during 1926 the company ‘were not in a position to discuss the sale of part of the Foundling Hospital grounds, as they were already committed in regard to this property’.[38] Nevertheless, the Board established a sub-committee on 17 November 1926 to examine the possibility ‘of acquiring a site on the Foundling Hospital Estate’, meaning the part of the Estate that had constituted the hospital site.[39] This option was boosted when it became known that FEL contemplated moving Covent Garden Market (in which FEL’s parent company, The Parent Trust and Finance Co. Ltd., held a large stake) to Bloomsbury, which, it was feared, meant levelling Brunswick and Mecklenburgh Squares as well as the hospital.[40] In a letter to The Times in June 1926, the local MP announced that Bloomsbury residents would seek ‘to resist the proposal to use the site for the vegetable market which now occupies Covent Garden; to preserve the present open spaces, with their trees; and, as far as is reasonable, to preserve the existing buildings’. A Labour MP, Ellen Wilkinson (“Red Ellen”), asked the President of the Board of Trade in Parliament on 30 November ‘whether, in view of the fact that there is no adequate open space in this crowded neighbourhood and that this land has been dedicated to the use of children for over 200 years, he will withhold his consent.’[41]

The new owners were Foundling Estates Limited, the syndicate established by White in May 1925, hereafter called FEL. The Board of Management secured FEL’s agreement to sell the freehold on the timber yard, 13 houses on Guilford Street (nos. 34-46), and Grenville Mews (property, south of 47-50 Guilford Street, on which Great Ormond Street had held a 999-year lease from 1915), which transactions were completed in March 1927 – see E in the hospital plan that was printed in subsequent annual reports – but during 1926 the company ‘were not in a position to discuss the sale of part of the Foundling Hospital grounds, as they were already committed in regard to this property’.[38] Nevertheless, the Board established a sub-committee on 17 November 1926 to examine the possibility ‘of acquiring a site on the Foundling Hospital Estate’, meaning the part of the Estate that had constituted the hospital site.[39] This option was boosted when it became known that FEL contemplated moving Covent Garden Market (in which FEL’s parent company, The Parent Trust and Finance Co. Ltd., held a large stake) to Bloomsbury, which, it was feared, meant levelling Brunswick and Mecklenburgh Squares as well as the hospital.[40] In a letter to The Times in June 1926, the local MP announced that Bloomsbury residents would seek ‘to resist the proposal to use the site for the vegetable market which now occupies Covent Garden; to preserve the present open spaces, with their trees; and, as far as is reasonable, to preserve the existing buildings’. A Labour MP, Ellen Wilkinson (“Red Ellen”), asked the President of the Board of Trade in Parliament on 30 November ‘whether, in view of the fact that there is no adequate open space in this crowded neighbourhood and that this land has been dedicated to the use of children for over 200 years, he will withhold his consent.’[41]

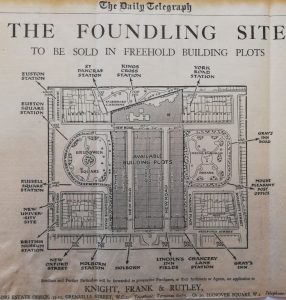

A private bill, The Covent Garden Market Bill, was introduced in the Commons, but the ‘force of public opinion’ was felt and it was withdrawn at the second reading stage on 17 February 1927.[42] The furore provoked by its plans meant that FEL might be persuaded to sell on the property and, keen to take advantage, the hospital’s Reconstruction Sub-Committee proceeded to sound out representatives of London County Council and the Foundling Estates Protection Association (the body established by residents in June 1926).[43] In March 1927, ‘the owners…, for the first time, applied to the Hospital’, and Sir Arthur du Cros, FEL’s chairman, pressed in May for a decision ‘with regard to the Foundling Site’: he wished ‘to know whether the scheme of moving the Hospital to the Site was likely to mature, either in whole or in part…’ At the same time, FEL advertised the sale of ‘THE FOUNDLING SITE comprising about NINE ACRES of FREEHOLD LAND with the beautiful Old Buildings’. Great Ormond Street made an offer of £100,000 for a mere four acres of the site, but FEL wanted £366,000. C.W. Beatty, advising Great Ormond Street, commented that ‘the owners desire to hold up the required Hospital site somewhat to ransom’ – or, as FEL put it, ‘in their opinion’ the Hospital ‘does not mean business’.[44]

Despite this false start, purchase of the Hospital site continued to be strongly favoured by both the Reconstruction Sub-Committee and the Medical Committee. As the latter argued, weighing ‘reconstruction of our present building’ against ‘the building of a modern hospital on another site’,

In either case, we realised that we must be inevitably forced to make a great public appeal for funds in the near future. In our opinion, arrived at after the most careful deliberations, if such funds could be obtained, the best policy would be to build a new Hospital on another site. The Foundling Hospital site, a part of the Foundling Estate, would provide an ideal position, for it is near the present Hospital, the site is a good one and [it is] associated in the mind of the Public with the care of the young for over a century.[45]

Or, as Stanley Hall, the architect, wrote, ‘It is one chance in a century of getting an ideal site for a Children’s Hospital in the heart of a dense population… The site is in every way ideal…’[46] However, progress was hindered by the expectation of great expense and by division in the Board of Management. Lord Wemyss, the chairman, deprecated the ‘amazingly ambitious schemes’ (‘schemes which seem to be the vision of megalomania’) of the Medical Committee and the Finance Committee (‘these watchdogs of economy fraternising with the wolves of extravagance’) and insisted that ‘the condition of our finances made it quite impossible for us to commit ourselves to so gigantic an outlay’; his intervention had caused the Board to agree in November 1926 ‘that no further steps be taken for negotiating for the purchase of a new site for the Hospital’, the first of many examples of vacillation.[47] Even the cheapest, four-acres option would cost £2,500,000 (including construction costs), which Sir John Murray (a senior Board member) considered totally unaffordable (‘Utopian’).[48] Hugh Macmillan’s accession to the chairmanship of the hospital in April 1928 brought an enthusiast for reconstruction to the fore, but the financial obstacle remained.

Bloomsbury residents generally favoured converting the former playground / forecourt of the Foundling Hospital to a children’s park, although some in the Foundling Estate Protection Association sought a general-use public park and others advocated building a hostel, Coram Hall, for Overseas Students at London University.[49] Notwithstanding vigorous campaigning (involving such luminaries as Herbert Asquith and Millicent Fawcett), there seemed little prospect of their raising the six-figures sum required to purchase the land, so the Association, in particular Appeals Committee chairman Philip Morrell, offered to rally public support (characterised by Murray, concerned as ever about the financial outlook, as ‘a spontaneous offer from the public and the neighbours to assist in collecting funds’ for a new hospital) for ‘the acquisition of the Foundling Site, partly (a) as a new site for the Hospital for Sick Children, and partly (b) as an open space for the benefit of the public, and especially for the benefit of children’. This culminated in a Board of Management decision on 11 April 1928 to set up a ‘Joint Executive Committee’ and an ‘Appeal Organisation’ to raise funds ‘to purchase the Foundling Hospital Site’, build a new hospital and lay out and maintain ‘an open space for the use of the Public’.[50]

However, as in the previous year, a price could not be agreed: the ‘eminent valuers’ appointed by the parties (the Joint Executive Committee and FEL) ‘found themselves unable to agree. After several weeks of patient discussion,’ the would-be purchasers reported in June, ‘the negotiations have broken down…’ Sir Arthur du Cros voiced ‘our special sympathy’ for the shared-site option but was clearly frustrated that, with no progress made, ‘a costly property has been left in expensive idleness… [T]ime presses, and nothing has been done.’[51] FEL resolved to proceed with the construction of ten-storey blocks of luxury flats (‘for the business and professional classes in Central London’) on the site and, accordingly, demolition of the Foundling Hospital buildings (already ‘gutted and rendered useless’ – du Cros) was completed towards the end of 1928. Janet Trevelyan, the historian’s wife, led a public campaign against FEL’s plans – but in November Great Ormond Street ‘had no practical proposal to put forward’ regarding purchase of the land and was reduced to lamenting ‘the imminent failure of this great project. The reason is solely the want of money.’[52] After the flats scheme was rejected by London County Council at the beginning of 1929, FEL approached the hospital in February with a proposal to sell six acres of the site for ‘a negotiable price of £480,000’ – but the Board could ‘not see their way to take any steps with regard to the new offer…’[53]

Jigsaw

The baton began then to be passed into other hands. The joint letter of the chairmen of Great Ormond Street and the Protection Association expressed the wish that ‘some person or persons of wealth and public spirit should even now [June 1928], at the eleventh hour, come forward and make a really generous contribution to a great public object’.[54] In other words, they ‘hope[d] that the intervention of a financial magnate will prove the solution’ and by late July 1928 ‘the Magnate’, Lord Rothermere, had expressed an interest.[55] Rothermere was reckoned to be the third richest man in Britain and the Daily Mail, his standard-bearer, had already been involved in campaigning against the Covent Garden and flats-development options.[56] In April 1929, after his return from a stay in the West Indies, it was reported that the ‘rescue of the Foundling Hospital from the imminent danger of building development has been assured’ by Rothermere’s having agreed to purchase the site for £525,000: £100,000 (in two equal instalments) was to be the peer’s personal contribution and, it was implied (but not stated), the rest (£425,000) would be raised from the general public.[57] In May 1929, the Board at Great Ormond Street resolved to ask Rothermere ‘whether he would be prepared to convey to the Hospital part of the Foundling Site … and, if so, on what terms’. Their letter, on 20 June, argued that, ‘The area required for a new Sick Children’s Hospital (some four acres) would leave the bulk of the Foundling site still available for the purpose already announced by you… The utilisation of part of the Foundling site for the Children’s Hospital is in no way incompatible with the utilisation of the greater part of it for children’s playing fields. Indeed, the two objects would seem to be peculiarly fit for association.’[58] But Rothermere’s earlier prevarication – his ‘predominant interest’ was ‘in open spaces & only subordinately in the Hospital’ – had evolved to the point where the ‘only condition’ of his aid was that ‘the entire site shall be used as a children’s park’.[59] As his representative put it in reply to the hospital’s approach, his aim had ‘all along been to preserve it [the site] intact as an open space for the benefit of the entire surrounding community. He regrets therefore that he cannot see his way to allocating any portion of the estate for any other purpose.’[60]

From August 1929, the Joint Committee of Voluntary Associations for the Welfare of Children and Young People (Foundling Site) ran the site as a playground for local children (above); the site was ‘kindly placed at their disposal for the purpose by Lord Rothermere’ who, seeing thousands of children happily at play, told one of the organisers ‘that this was the way to prevent revolutions’.[61] A ‘shattering blow’ (Trevelyan) was delivered, however, towards the end of the two-year period in which the sale was to be completed. In December 1930, the rather mercurial Rothermere informed the Joint Committee that he would not exercise his option to buy the site, and in February 1931 he wrote to tell Sir Howard Frank (of Knight, Frank and Rutley, handling the sale for FEL) that ‘the steadily increasing oppressive taxation, combined with the general depression in trade, prevents me from putting up the entire amount which, at one time, it was my intention to do in respect of the Foundling Hospital Site’ – which was not the plan announced in 1929, although Janet Trevelyan’s later account also claimed that Rothermere had offered to cover the entire £525,000 cost.[62] The Agent of FEL, briefly reviving the Great Ormond Street option, wrote to the Board regarding ‘the present position of affairs in connection with the Site of the old Foundling Hospital which had arisen in consequence of the decision of Lord Rothermere not to exercise his option to purchase this Site’. The hospital’s Building Committee was ‘asked to watch the development of events’ and Mrs Trevelyan, who had sought the hospital’s backing, was ‘informed with regret that the Board do not see their way to support her scheme in connection with this Site’.[63] It seems likely that it was Rothermere’s wobble which occasioned Stanley’s Hall preparation of a plan (March 1931) to rebuild on the Foundling Hospital site.[64]

Trevelyan’s Joint Committee launched a public appeal for funds in February 1931. Money came in very slowly – ‘the position was indeed pretty desperate… [I]n vain was the snare spread in the sight of the owners of big money!’ (Trevelyan) – and they were still £400,000 short in mid-May 1931, when the owners advertised the sale of the site as building plots.[65] By this stage, of course, the financial markets had crashed and the Great Depression was under way. But ‘the Depression was our friend as well as our enemy, by making impossible the grandiose schemes of sale and development that the Syndicate [FEL] had planned’. Rothermere told Trevelyan that she ‘ought not to worry much about [the expiry of] the option, because the owners would have great difficulty in disposing of their property’.[66] Sir Harry Mallaby-Deeley bought the controlling interest in FEL in April 1933 and announced that he was in ‘full sympathy’ with the idea of a children’s playground.[67] Assisted by Lord Rothermere (who eventually purchased the southern three-eighths of the site for £170,000) and Lord Riddell, the Pilgrim Trust, London County Council (under Herbert Morrison) and the Foundling Hospital (see below), the Appeal Council was able to announce a successful outcome on 3 July 1934 (‘The Foundling Site Saved’) and the combined trusts completed the purchase of the site in December 1935.[68]

But the main Hospital site went to make the Coram’s Fields children’s park – formally, Coram’s Fields and the Harmsworth Memorial Playground – which opened in July 1936. Listing the park’s first benefactors, the bronze plaque at the entrance acknowledges ‘the co-operation of the Governors of the Foundling Hospital’. The latter had maintained a presence within the Foundling Estate, deciding in July 1925 to hold onto 40 Brunswick Square, north of the hospital site, by giving Secretary Nichols a 13-year lease on the house, at £250 per annum; this would serve as the post-sale London office of the Hospital.[74] When Janet Trevelyan approached the governors in January 1931, ‘making it plain that we did not share in the popular outcry against them for their inevitable sale of the property, but pleading that they should give us [the Joint Committee] some assistance,’ they, restricted by the founding charter, turned her down and resisted considerable pressure on the subject over the following months; ‘we have neither the powers nor the means to divert our funds to such a purpose,’ Nichols explained. ‘We sold our site to enable our babies to get into the country. Our job is to look after them and devote our entire income to their needs [and] not to contribute to playing fields for London children.’[75] However, the Foundling Hospital decided on 9 May 1934 to buy (‘repurchase’) 40 Brunswick Square, with an adjoining strip of land, 2.5 acres in all (one quarter of the Foundling site), for £100,000 (£1 per square foot).[76]

Trevelyan was consulted during April – she assured Nichols that her committee ‘rejoices to learn of the decision of the Governors of the Foundling Hospital to take a large share in the saving of the Northern part of the Site in the manner you propose’ – and duly informed of the Governors’ formal resolution:

The Offices of the Foundling Hospital,

40, Brunswick Square,

London, W.C.1.

9th May, 1934.

Dear Mrs. Trevelyan,

The Governors of the Foundling Hospital have hitherto felt unable to subscribe to the many appeals which have been made to them to contribute to the Fund which you have raised for the purpose of saving our old Hospital Site, as in their opinion such an application of their funds would not have been in accordance with the terms of their trust; moreover, they would have been acting wrongly if they had allowed any of the funds of the Charity to pass from their sole control.

Now that the Buildings at Berkhamsted are practically completed and the expenditure on providing a new home for the children can be estimated with some degree of accuracy, the Governors feel that they might be justified in extending the ambit of the work which Captain Coram instituted some two hundred years ago.

They propose, therefore, to acquire at a cost of approximately £100,000 the northern portion of the site (plan enclosed) in which would be included the Children’s Nursery and the Swimming Bath, and to utilise the site as an Infant Welfare Centre, a Day Nursery and Nursery School and for other work for little children…

It is not their intention to erect further buildings on the site, except for the purpose of making a small enlargement to their present Offices and for the general purposes of the undertaking… [T]he Governors will maintain their portion primarily as an open space and generally for the welfare of young children.

I am,

Yours faithfully,

(Sd) Reginald H. Nichols.

Secretary.[77]

The weight of public opprobrium (‘popular outcry’) may have influenced this decision, but there is a suggestion here of a more fundamental change, which Treasurer Sir Roger Gregory voiced explicitly: given that ‘for many years now and more noticeably since the end of the War the number of applications for the admission of children to the Hospital has been on the decline’ (and ‘the class of applicant for admission has been inferior to those received in years past’), that an increasing number of societies were helping mothers to keep their illegitimate children and that adoption was more widespread, ‘the question of extending the scope of the Charity’ arose and this was reflected in the intended, variegated functions of the re-purchased site.[78] This rationale presaged elements of the discourse which brought the closure of the Foundling Hospital in 1954 – it is astonishing to think that Gregory wrote in such terms even before the grandiose new building was completed at Berkhamsted – and, over the last half-century, Coram’s development of a tremendous range of children’s services at Bloomsbury.

The Purchase Agreement was signed on 1 August 1935, but the transaction, because of restrictive terms in the Foundling’s charter, required approval by Act of Parliament, delaying completion until 24 July 1936. This took care of the last piece of the jigsaw – ‘the whole Site would be saved’ (Trevelyan) – and was a useful contribution to the cause of the children’s park, as it effectively sweetened the deal for the vendor. The Appeal Council was grateful to the governors, who ‘stepped in, in so magnificent a manner, to complete the memorial to their founder, Thomas Coram, and to continue the work for little children which was started on this site nearly 200 years ago’.[79] (40 Brunswick Square was rebuilt (and expanded) in 1937-39 as the Foundling Hospital’s London office, which in 1998 (opening in 2004) became the Foundling Museum.)

In a sense, then, the Foundling did more to assist the Coram’s Fields project than it did to advance the reconstruction of the Hospital for Sick Children. So, never the best of neighbours. Even charities must look to their own interests and the welfare of those they were appointed to protect.

Nick Baldwin, the Archivist of Great Ormond Street Hospital, gave me invaluable assistance in the preparation of this work; his expertise and patience were exceptional. The remaining mistakes are my own.

[1] The Chief Executive of Coram: ‘Please note that our collection is managed by the London Metropolitan Archives and owned by Coram which is the Foundling Hospital and the archive is the Coram Foundling Hospital Archive… Whenever used, the first reference to The Foundling Hospital in each media/article, including commentary, should indicate that it continues today as Coram, with an online link (http://www.coram.org.uk), with the following wording: “Foundling Hospital, which continues today as the children’s charity Coram”.’

[2] Minute Book of Proceedings of the Provisional Committee: Hospital for Sick Children (hereafter HSCPC Minute Book), page 1, 30 January 1850. The Times, 16 February 1850, Appeal on Behalf of a Hospital for Sick Children, 12 February 1850. Correspondence Album of the Hospital for Sick Children, GOS/8/151/1, 17b, Collector’s Card.

[3] HSCPC Minute Book, 43, 13/3/51. The public meeting on 18 March was reported in The Morning Chronicle, 19 March 1851.

[4] HSCPC Minute Book, 49, 1 April 1851.

[5] Ibid., 52, 54, 29 April, 6 May 1851. Alec Forshaw has shown that the house was ‘effectively vacant’ in 1851, occupied only by two charwomen and the two daughters of one of them. Alec Forshaw, An Address in Bloomsbury: The Story of 49 Great Ormond Street (Bath, 2017), 145.

[6] HSCPC Minute Book, 58, 3 June 1851. ‘London’ would be omitted before the hospital opened in 1852.

[7] Shaftesbury chaired the Board of Health meetings every time he was present, Chadwick took the chair in his occasional absence.

[8] Minutes of Meetings of General Board of Health, MH 5/5, 135, 139 (1851), 17, 21 June 1851.

[9] HSCPC Minute Book, 61, 24 June 1851.

[10] Minutes of the General Committee of the Foundling Hospital, A/FH/K/002/051, 21 June 1851.

[11] Ibid., 28 June 1851, report of 27 June 1851.

[12] The Morning Chronicle, 19 March 1851.

[13] HSCPC Minute Book, 101, Official Sanction of the Board of Health, 21 January 1852.

[14] Minutes of the General Committee of the Foundling Hospital, A/FH/K/002/051, 28 June 1851, report of 27 June 1851.

[15] Ibid..

[16] John Brownlow, Memoranda; or, Chronicles of the Foundling Hospital, including Memoirs of Captain Coram (London, 1847), 175; The History and Design of the Foundling Hospital, with a Memoir of the Founder (London, 1858), 15-16; History and Objects (London, 1865), 47. Brownlow became Secretary in 1849. Infectious diseases caused many but by no means all of the deaths during the General Reception. See D.S. Allin, The Early Years of the Foundling Hospital 1739/41-1773 (unpublished, 2010), 109-13, 142-49, 170-75.

[17] Letterbook, A/FH/A/06/002/011, page 213, Brownlow to Wood, 19 June 1851.

[18] Ibid., 217, Brownlow to Spence, 3 July 1851; ibid., Brownlow to the Secretary of the General Board of Health, 9 July 1851. The Board had ‘no power to interfere in the matter’. Secretary’s Correspondence, A/FH/A/06/001/109/002, Macaulay to Brownlow, 11 July 1851.

[19] General Board of Health, MH 5/5, 142, 143, 25, 26 June 1851. HSCPC Minute Book, 61, 62, 24 June, 1 July 1851.

[20] Ibid., 63, 8 July 1851.

[21] Ibid., 65, 13 August 1851.

[22] Ibid., 70, 7 November 1851.

[23] General Board of Health, MH 5/5, 5 (1852), 8 January 1852. HSCPC Minute Book, 93, 26 January 1852, including Austin to Bathurst, 21 January 1852.

[24] Secretary’s Correspondence, A/FH/A/06/001/110/016, West to Brownlow, 9 February 1852.

[25] The Morning Chronicle, 19 March 1851.

[26] Shaftesbury’s concerns (‘frustration and discontent’) regarding the Board of Health are described in Geoffrey B.A.M. Finlayson, The Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury 1801-1885 (London, 1981), 277-92, 352-61. Georgina Battiscombe, Shaftesbury: A Biography of the Seventh Earl 1801-1885 (London, 1974), 224 et seq..

[27] HSC, Album (Fundraising), 79.

[28] Forshaw, An Address in Bloomsbury, 173.

[29] The Daily Mail, 2 January 1923. R.H. Nichols and F.A. Wray, The History of the Foundling Hospital (London, 1935), 323.

[30] Report of the Sub Committee appointed for the sale of the Foundling Hospital and Estate, A/FH/A/16/004/001, 23 October 1923.

[31] ‘The Governors, doubtless with a true sense of their guardianship, have sold the site for a commercially satisfactory sum. What becomes of the stately old place does not concern them – its memories have been resolutely put behind, and they take their departure with the comfortable assurance that their charges will be fully equipped for a physically healthy and an efficient future. Will the speculative builder do his best or his worst…?’ Anne Page, The Foundling Hospital and its Neighbourhood, published by the Foundling Estate Protection Association, 1929, 28-29.

[32] A/FH/F/15/002/003, Foundling Estate (1920s).

[33] Minutes of the General Committee of the Foundling Hospital, A/FH/K/002/051, 155, 239, 29 January, 5 June 1924.

[34] The Times, 25 June, 15 September, 26 November (sale) 1926.

[35] GOS/4/3/xii, Meeting of the Sub-Committee on Reconstruction, 2 April 1925.

[36] Ibid., James McKay (Secretary), Schemes Under Consideration, October 1925. Acquisition of the timber yard and houses in Guilford Street now meant their purchase.

[37] GOS/4/3/xii, Meeting of the Sub-Committee on Reconstruction, 1 December 1925; ibid., Meeting of the Medical Committee, 2 December 1925. The Hospital for Sick Children Board of Management Minute Book, Volume 26, 390-91, 21 October 1925; Volume 27, 28-29, 16 December 1925 (hereafter BMMB).

[38] BMMB, Volume 27, 51, 78-80, 99-100, 119-20, 147, 155, 163, 206, 281, 293, 304, 325, 20 January, 17 February, 17 March, 28 April, 19 May, 16 June, 20 October 1926, 19 January, 16 February, 16 March 1927.

[39] Ibid., 231, 17 November 1926.

[40] The chairman of the Parent Trust and Finance Company would not allow any ‘sentimental aspects’ to prevail over ‘the business side of the case’. A/FH/F/15/002/003, Chairman’s Speech, 23 July 1926.

[41] The Times, 9 June 1926, John W. W. Hopkins MP to the Editor, n.d.. Parliamentary Debates, Fifth Series, Volume 200, 985, 30 November 1926.

[42] Ibid.. Parliamentary Debates, Fifth Series, Volume 202, 432, 1073, 11, 17 February 1927. For the campaign leaflets, see A/FH/F/15/002/003, London Foundling Estate Preservation Committee, June 1926. A/FH/F/15/002/003, Foundling Estate Protection Association, February 1927.

[43] GOS/4/3/xii, Meeting of the Sub-Committee on Reconstruction, 14 December 1926. BMMB, Volume 27, 249, 277, 22 December 1926, 19 January 1927, enclosing Report of the Reconstruction Sub-Committee.

[44] GOS/4/12, Reports of the Reconstruction Sub-Committee, 9 May, 28 October 1927; ibid., Beatty to McKay, 27 October 1927; ibid., Statement of Sir John Murray, 11 November 1927. GOS/4/3/xii, Report by James McKay on the Foundling Hospital Site, 15 September 1927. The Daily Telegraph, 27 May 1927.

[45] GOS/4/3/xii, Report (approved by the Medical Committee) of the Medical Sub-Committee, 2 November 1927.

[46] GOS/4/3/xii, Hall to McKay, 4 April 1928. Acquisition of the Foundling site ‘seemed to offer an ideal, almost a providential, solution of the problem’ of the hospital’s need for new premises. The Times, 1 November 1928, Macmillan et al to the Editor, n.d..

[47] BMMB, Volume 27, 255-58, 22 December 1926, enclosing Wemyss to McKay, 29 November 1926.

[48] Ibid., Volume 28, 116, 11 November 1927, Statement of Sir John Murray, 11 November 1927.

[49] On the early proceedings of the Association, which operated out of 10 Mecklenburgh Square, see Papers collected by Marjorie Bunbury, A/FH/F/15/002/001-5 and A/FH/G/01/001.

[50] BMMB, Volume 28, 225, 22 February 1928, enclosing Report of the Reconstruction Sub-Committee, February 1928; ibid., 251, 21 March 1928, enclosing Notes of an Interview between Mr. Philip Morrell and … The Board of Management, 21 March 1928; ibid., 263, 11 April 1928, enclosing Report of a Conference, 30 March 1928.

[51] The Times, 18 June 1928, Hugh Macmillan (GOSH), R.F. Cholmeley (Foundling Estate Protection Association) and Philip Morrell (Joint Appeal Committee) to the Editor, 16 June 1928; ibid., 21 June 1928, Du Cros to Lady Oxford and Asquith, n.d.. Du Cros’s letter sparked off a considerable debate (‘it would make poor Coram turn in his grave to see his precious site so misused’ – Lady Oxford); Sir Arthur, Philip Morrell and Lady Oxford were the main players, but GOSH did not take part. Ibid., 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 June, 21, 24 July, 27 August 1928.

[52] BMMB, Volume 28, 40, 21 November 1928. The Times, 1 November 1928, Macmillan et al to the Editor, n.d. (‘imminent failure’).

[53] GOS/4/12, James McKay (Secretary) to Chadwyck-Healey, 2 February 1929. BMMB, Volume 28, 20 February 1929.

[54] The Times, 18 June 1928, Macmillan et al to the Editor, 16 June 1928. See also ibid., 29 June 1928, Lady Oxford to the Editor, 28 June 1928; ibid., 1 November 1928, Macmillan et al to the Editor, n.d..

[55] GOS/4/12, Macmillan to Oliver Chadwyck-Healey, 30 June 1928; ibid., Chadwyck-Healey to Macmillan, 24 July 1928.

[56] Ricci de Freitas, Tales of Brunswick Square: Bloomsbury’s untold past (London, 2014), 36-7. S.J. Taylor, The Great Outsiders: Northcliffe, Rothermere and the Daily Mail (London, 1996), 253.

[57] The Times, 15 April 1929. The Daily Mail, 15 April 1929.

[58] BMMB, Volume 28, 171, 194, 17 April, 15 May 1929; ibid., 216, 19 June 1929, enclosing MacMillan to Rothermere, 20 June 1929.

[59] GOS/4/12, Macmillan to Chadwyck-Healey, 24 July, 10 August 1928. The Daily Mail, 15 April 1929.

[60] GOS/4/12, Outhwaite to Hugh Macmillan, 27 June 1929.

[61] A/FH/G/01/001, A Holiday Play Centre on the Foundling Site, Summer 1929 (‘kindly’). Janet Trevelyan, Two Stories (London, 1954), 152, The Second Story: The Saving of the Foundling Site. For the full story of the development of the playground (and day nursery and outdoor paddling pool), see ibid., 151-58. ‘Thus did we dig ourselves in at the Foundling Site…’ Ibid., 157.

[62] The Times, 28 February 1931, Rothermere to Frank, 25 February 1931. Trevelyan, Two Stories, 150, 158-59. Rothermere explained to Trevelyan that even rich men like him ‘simply can’t realize their securities at a time like this’ (the Depression). Ibid., 176.

[63] BMMB, New Series, Volume 1, Minute No. 12, 18 February 1931.

[64] GOS/4/28, ‘Hospital for Sick Children on the Foundling Site’, March 1931, in Stanley Hall to McKay, 10 March 1931.

[65] Trevelyan, Two Stories, 171, 173. The Daily Telegraph, 20 May 1931.

[66] Trevelyan, Two Stories, 161, 179. The Times, 21 May 1931, Further Appeal for Contributions. The Times of 25 June carried the first published list of the several thousand subscribers to the appeal, which had so far yielded £34,231 (‘given and promised’), which sum had risen to about £99,000 by 28 July. Ibid., 25 June, 29 July 1931.

[67] Ibid., 11 April 1933. The ‘quite benevolent’ Mallaby-Deeley contributed £36,000 towards buying himself out! He was the ‘anonymous donor’ reported in the press. Ibid., 10 January, 3 July 1934. Trevelyan, Two Stories, 214-15, 218.

[68] Ibid., 213-22. The Times, 3 July 1934, 17 December 1935.

[69] Trevelyan, Two Stories, 191, 196. The Times, 7 July 1931. Punch, 24 June 1931.

[70] The Seventy-ninth Annual Report of the Board of Management, 1930, 14. Janet Trevelyan’s story of how Coram’s Fields came into being did not include a single mention of Great Ormond Street.

[71] Annual Report, 1930, 14.

[72] BMMB, Volume 30, 196, 26 November 1930. Annual Report, 1930, 14, 203, 206, 220, 224. Thousands of pounds were needed merely to buy out the leases of the Dollings (sisters) and the Guilford Street tenants.

[73] Annual Report, 1931, 13.

[74] Minutes of the General Committee of the Foundling Hospital, A/FH/K/002/444, 21 July 1925.

[75] Trevelyan, Two Stories, 164. The Morning Post, 12 March 1931 (Nichols).

[76] A/FH/K/01/011, Minutes of the General Court, 9 May 1934. A/FH/G/01/003, northern section.

[77] A/FH/G/01/002, Trevelyan to Nichols, 16, 27 April 1934; ibid., notes by Nichols, 19 April 1934; ibid., Nichols to Trevelyan, 25 April, 9 May 1934. The Times, 3 July 1934, the Foundling Hospital site in sections. Trevelyan, Two Stories, 216-17.

[78] A/FH/G/01/002, Treasurer’s Confidential Memorandum to the Governors.

[79] Trevelyan, Two Stories, 217, 219. The Times, 3 July 1934, including Nicholls to Trevelyan, n.d.. The Times had the less exultant ‘satisfactory’, rather than ‘magnificent’, but the press release drafted by Trevelyan, and agreed with the Hospital, said ‘magnificent’; Nancy Astor thought it both ‘magnificent’ and ‘glorious’. A/FH/G/01/002, Proposed Press Statement; ibid., Astor to Sir Roger Gregory, 25 April 1934. The idea that Rothermere sold the property to the Foundling Hospital is a myth, for he was never the owner of that section and had no part in the sale (documented in A/FH/G/01/004).