The Treaty of Sèvres of August 1920 dealt with the entirety of the Ottoman Empire, including a large swathe of the Middle East. This study is focused on the part of the treaty which dealt with the lands awarded to Greece, and, within that, it is the story of Smyrna which dominates the picture. It is proposed, then, to describe and explain the disastrous fate of the Greeks of Smyrna.

The Greek state created in 1832 encompassed a small majority, possibly only a minority, of Greeks. The Sultan’s coming into the First World War as Germany’s ally in November 1914 meant that if Greece joined the Allies she might be able, should they win, to expand at the expense of a dismantled Ottoman Empire. As Lloyd George put it, an opportunity “opened out to Greece for adding to her realm the millions of Greeks who lived a menaced and anxious existence under the shadow of Turkish despotism…”[1] Largely Greek western Asia Minor (including Smyrna) and Thrace (Eastern, which was mostly Greek, and Western, where they were a minority) might be gained.[2] The contest between Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, keen to join the Allies and secure these lands, and the Germanophile King Constantine, who favoured neutrality, was won by the former when, in June 1917, Constantine was forced by the Anglo-French blockade to flee to Switzerland. He was replaced on the throne by his son, Alexander, and Venizelos took full control of Greece and brought her into the war.

Greece made a substantial contribution to the Allied war effort, subscribing ten divisions to the Macedonian front campaign which decided the outcome in the Balkans. The attitude of many who went to Paris in 1919 was also coloured by the image of the glories of Ancient Greece, which suffused the mind of every classically educated Westerner.[3] Moreover, the shattering of Ottoman power, which had protected the Near East against Britain’s rivals, meant that the British now looked to an alternative: Greece, strengthened and expanded, was projected to be the carrier of British interests in the eastern Mediterranean.[4] The long history of Turkish atrocities created a strong animus, to the advantage of Greece, many in the West sharing Harold Nicolson’s perception of the “most brutal savagery” of the “Anatolian marauders”.[5] Of all the peoples of the Balkans – the beaten Bulgarians, the over-ambitious Romanians, the Slavs whom the Italians hoped to curtail, the conquered Montenegrins and the defenceless and disposable Albanians – it was the Greeks who had the following wind as they sailed into the conference rooms of Paris.

Above all, it was the personality of Venizelos which proved to be his country’s principal asset. He was the darling of the conference, charming, erudite, everyone’s favourite dinner guest. After hearing Venizelos present the Greek claims to the Council of Ten on 3 February, Allen Leeper noted in his diary that, “Venizelos made the most wonderful speech on Gk claims.” He told his brother that,

Venizelos stated his whole case most wonderfully. We all thought it was the most brilliant thing we’ve ever heard, such amazing strength & tactfulness of argument combined… It was the most interesting two hours I ever spent. He covered N. Epirus, Thrace & the islands & gets on to the Asia Minor question to-morrow.[6]

Leeper returned next day “& heard Venizelos finish his case – two hours on the Greek claims on Asia Minor. He was intensely interesting & impressed everyone very favourably, though he hardly reached the marvelous [sic] success of yesterday (the best thing I ever heard).”[7] Summing up for his father, Leeper declared that “Venizelos was wonderful. Though I’ve met & talked & dined with him several times, I’d never heard him on a great occasion & my admiration is enhanced, if possible, a hundredfold. Whether in detail he is right or wrong, what a great man!”[8] Nicolson famously declared that Venizelos and Lenin were “the only two really great men in Europe”.[9] The Nicolson-Leeper infatuation with Venizelos continued: “an excellent speech”, “V. in great form”, “one of his charming speeches”, “an exceedingly nice dinner”, “very charming talk alone with him”, “we [Leeper and Nicolson] had such a charming talk with him. How one does love that man.”[10]

Having such fans in the engine room of the British delegation was surely helpful to Venizelos, but his most important admirer was Lloyd George, who later called him “the greatest statesman Greece had thrown up since the days of Pericles” and hailed “his brilliant oratorical gifts” and “magnetic personality”.[11] A doubter at the time as well as later, Robert Vansittart thought that Lloyd George “was bamboozled by Venizelos… The Cretan was the worst influence in Lloyd George’s life, and in the end its undoing.”[12]

Stumbling into Smyrna

In the Commission for the Study of Territorial Questions Relating to Greece (the Greek Committee) in February-March 1919, the British and French proposed awarding Smyrna, where the Greeks were the dominant element, to Greece, along with a hinterland (most of the vilayet of Aidin) in which there was almost certainly a Turkish majority. The Italians, who regarded Greece as a regional rival and also aspired to Smyrna, were strongly opposed. The Americans were divided between Hellenophiles and those, like William Westermann of the delegation’s Western Asia section, who wanted to respect the overall Turkish majority in western Anatolia and feared that transferring it to Greece would cause a return to war. It was not until May 1919 that a decisive step was taken, when the Greeks were allowed to occupy Smyrna. As Wilson grew frustrated with the Italians in relation to an entirely separate issue, the future of Fiume and Dalmatia on the eastern Adriatic, he came to regard the Greek claim in Asia Minor more sympathetically than the counter-claim from Italy. He appreciated the fact that Greece’s claim to Smyrna, with its Greek majority, was stronger than Italy’s: there were almost no Italians in Asia Minor. Wilsonianism was more in tune with the Greek cause than with an Italian policy that was based on wartime pledges and on balance-of-power ideas that, he believed, had wrought war and destruction in Europe. This made Wilson amenable to Lloyd George’s proposal to push the Greeks into Smyrna.

Both Greeks and Italians had wanted for months to send forces to the claimed lands in Asia Minor. But it was the Italians who acted first: at the end of March 1919, they landed men at Adalia, on the southern coast, citing “disturbances” in the town; they came and went several times but by May were more or less permanently based at both Adalia and Marmaris (south-west).[14] The Big Three would never forgive their ally for this unilateral action. Compounding the problem of Italy’s hawkishness, from the Greek perspective, there were allegations of Turkish assaults on Greek civilians in the countryside around Smyrna. “Murders [of Greeks] take place almost every day,” it was claimed, and a “wholesale massacre of Greeks” was anticipated by a British naval officer at Smyrna.[15]

The Italians, infuriated by Wilson’s public opposition to their Adriatic claims, quit Paris on 24 April and their brief absence meant that they were not present to oppose the decision to allow the Greeks to occupy Smyrna. In the Council of Four, Lloyd George spoke of “the massacres of Greeks by Turks” as proven fact and on 2 May he accepted the idea that the Turks were “stimulated” by Italy to continue “their policy of oppression and massacre”.[16] On 5 May, Wilson and Lloyd George combined to present a picture of Italy as a rogue power that must be checked. Lloyd George, scare-monger in chief, recalled the “uncommonly well concealed” Italian strike at Tripoli in 1911 and claimed that he was “suspicious of a similar expedition now to Asia Minor”. He proposed to allow the Greeks to occupy Smyrna (“since their compatriots were actually being massacred at the present time and there was no one to help them”) – and he was anxious to have this agreed before the Italians returned to Paris: “if they discussed it with the Italians, they would anticipate them.”[17]

Next day (6 May), the last before the Italians resumed their places, the decision was made. Lloyd George said that Venizelos “should be allowed to land two or three Divisions at Smyrna to protect his fellow-countrymen in Turkey”. Clemenceau and Wilson agreed. When Lloyd George proposed that they should authorise Venizelos “to send troops on board ship to Smyrna to be kept there ready for landing in case of necessity,” Wilson “asked why they should not be landed at once? The men did not keep in good condition on board ship.” Lloyd George “said he had no objection”.[18] Lloyd George was the driving force behind this momentous and disastrous decision. Preoccupied with German matters, Clemenceau merely followed his lead, but Wilson, fired by animosity towards the Italians, gave enthusiastic support.

All three leaders understood that this step would lead to Greece’s permanent acquisition of Smyrna. Wilson stated (inaccurately) that “the report of the Greek commission was now unanimously in favour of giving this area to Greece” and Clemenceau sent Basil Zaharoff, the Greek arms dealer, a telegram saying “Vous avez Smyrne”.[19] When Lloyd George dined with Venizelos on 9 May, he “told him categorically that he was not being asked to send troops merely to do police work for the Powers … but that he was asked to do so because the Supreme Council definitely intended to allot Smyrna eventually to Greece.” Frances Stevenson wrote that Lloyd George was “trying to get Smyrna for the Greeks” and Venizelos’s diary had Lloyd George saying that “Greece has great possibilities in the Near East and you must be as powerful as possible in the military sense in order to take advantage of them.”[20]

Venizelos appeared before the Council several times between 7 and 11 May to discuss practical arrangements. The Italians were not invited; Prime Minister Orlando’s “unexpected appearance” on 7 May was “very awkward – we were going to thrash out the Greek occupation of Smyrna… They want the move of Greeks to Smyrna to be secretly done … and they are not going to tell either Italy or Turkey until the whole thing is well on the way.”[21] Much of the Council’s discussion was devoted to the danger that, if informed, the Italians “will immediately warn the Turks”. At one point, inverting enemies and allies, Clemenceau “asked if the Turks could be warned without warning the Italians also?” With the landing scheduled for the 15th, the Italians were told on 12 May (“we didn’t want to give orders without first consulting the Italian government,” Clemenceau told them, shamelessly), late enough to prevent any reaction. Orlando and Foreign Minister Sonnino passively accepted the démarche.[22]

The Italians could not have known the extent to which they had been traduced and deceived, nor did they realise that their consent would later be used to accord them shared responsibility for a decision in which they had no part. Sir Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, believed that putting in the Greeks meant “starting a new war… the whole thing is mad… Venizelos is using the three Frocks [Lloyd George, Wilson and Clemenceau] for his own ends… I told Lloyd George he was making a lot of trouble with the Turks and the Italians for nothing; but he would not have it…” As for how the Italians were handled, “What rotten behaviour to a friend and Ally.”[23]

The Greek occupation of Smyrna, involving some 20,000 men, began on 15 May. However, they “made a very bad start” (Vansittart) when, soon after landing, the soldiers (and local Greeks) attacked and killed hundreds of Turks, including prisoners.[24] Other atrocities followed as the Greek army moved into the hinterland. Ultimately, the most important result of the Greek occupation of Smyrna was the stimulus it gave to Turkish nationalism. Nationalist resistance had been organising quietly since the end of the war, but the Greek occupation of Smyrna was a turning point. Those Turks who had hoped for a moderate peace learnt that they could expect nothing from the Christian powers. When, wrote Churchill, “the Turkish nation” realised that part of it would be subject to “the hated and despised foe of generations [the Greeks] … from that moment, Turkey became uncontrollable… [T]he Turk was still alive.”[25] Reserve officers slipped across the Bosphorus from Constantinople to join the resistance. The most notable departure was that of Mustafa Kemal, who left on 16 May to become the Inspector of the Ninth Army at Samsun on the Black Sea, the beginning of his role as a revolutionary soldier-politician.

Becalmed

The rise of Turkish nationalism meant that the Allies (and Greece) were now involved in a race against time: could the peace treaty be made and enforced before the Turks had the strength to resist it successfully? One reason for Kemal’s victory in this race was the delay caused by Wilson’s need to secure his own people’s consent for projected American mandates over both Armenia (in the east) and Constantinople. At the end of June, the Big Three came close to agreeing on the terms to be presented to the Turks. On 27 June, however, the Council agreed to suspend further consideration of the treaty until Wilson, on returning home, could determine the American position.[26]

The following months saw nothing but frustration for the Greeks. At the end of July, a pact between Italy and Greece saw them agreeing to share the spoils, with Greece getting Smyrna, but Wilson was “distressed” by the “greed and utter selfishness” that he saw in this agreement and was now, incredibly, as critical of Greece as of Italy: “the more the Greek hand is shown in this business the less I like the way it is used…”[27] By October, Lord Curzon, soon to follow Balfour as Foreign Secretary, had concluded that “to get the Greeks out of Smyrna” was “vital for a pacific settlement of the Middle East”.[28] Also in October, the Interallied Commission of Inquiry into the May events at Smyrna severely censured the Greek military. Presenting this report in the Council, Clemenceau claimed that the Greeks “had been sent to Smyrna on the clear understanding that their occupation should not be taken as equivalent to a definite attribution of territory to them”.[29]

Venizelos alleged Turkish “outrages” against Greeks outside the occupied zone, but Sir Henry Wilson, in response, told him “that he had ruined his country and himself by going to Smyrna… He realizes that he is in a hopeless position… The old boy is done.”[30] Sir Henry was aware that Mustafa Kemal and his supporters now had control (albeit imperfect) of unoccupied Anatolia.[31] The story of Kemal’s reconstruction of the national movement and the army is one of the cornerstones of modern Turkish patriotism, but it was told at the time by the increasingly anxious Allied commanders in the region and Lloyd George’s later charge that those commanders failed to keep the leaders informed – “Our military intelligence had never been more thoroughly unintelligent” – was disgracefully unfair.[32] Admiral Webb in Constantinople, for example, reported in October that, “galvanised” by resentment against “the hated and despised Greek”, the nationalist tide had risen steadily, “day by day, week by week, until to-day the Allies are confronted with an entirely different Turkey”. He pleaded desperately for the peace terms to be “settled and announced with the least possible delay and certainly within the next few weeks”.[33] Vansittart, who read the incoming despatches, wanted to press or even to bypass the Americans:

The process of waiting for America, coupled with the folly of putting the Greeks into Smyrna, is rapidly putting an eastern “settlement” more out of touch.

Could anything be said by the Conference to President Wilson, or is it impossible to try to hurry his cattle?[34]

I suggested in a minute last week that President Wilson wd have to be told that the delay is making the situation worse & worse. It is 100 to 1 America won’t anyhow take the Armenian mandate & it is very doubtful if we shall gain anything by waiting indefinitely for America who wasn’t at war with Turkey. If she doesn’t take a mandate she shouldn’t be admitted to the settlement, which cd proceed without her.[35]

Wilson suffered strokes in September and October 1919, ending abruptly his campaign tour of the West to secure support for Versailles and the League of Nations. Finally, the logjam was broken on 19 November 1919 when Senate votes against the Treaty of Versailles made it clear that ratification was unachievable, and it was all but inevitable now that America would neither be joining the League of Nations nor accepting League mandates to govern Armenia and Constantinople.

Sèvres

Britain and France proceeded to seek a settlement without the United States, “America having disappeared from the scene as a factor in the settlement of the East”.[36] At the London Conference in February 1920, they agreed to leave the Sultan in Constantinople (despite Curzon’s angry protest that they were squandering the opportunity to expel “the Turk” from Europe), but his government would be shackled with tight financial and economic controls, arms limits and the guaranteed protection of minorities.[37] The London Conference also gave Eastern Thrace to Greece and confirmed that Armenia was to be independent, and Italy and France were awarded spheres of influence (economic priority zones) in southern Anatolia. Venizelos restated the case for his country’s acquiring Smyrna, which the French and Italian Premiers (Millerand and Nitti) warned would mean war with the Turks. For Lloyd George, the “true friend of the Entente Powers [Venizelos] … should not now be thrown over”; he would allow only “nominal sovereignty to the Turks in order to save their face”. The Conference decided to leave Turkey sovereign over Smyrna but imposed terms – an administration appointed by the Greek government, a Greek garrison and a local Parliament which could apply after two years to the League for incorporation into Greece (which the League might settle by plebiscite) – that amounted to annexation by Greece.[38] A specially convened Smyrna Committee decided that the transferred territory should comprise mainly of Smyrna and Aivali, excluding mostly Turkish southern Aidin.

The British, French and Italian High Commissioners in Constantinople warned that the Turks would never accept the proposed losses: such a treaty would lead to the “widespread massacre of Christians in Asia Minor and Thrace…” Britain’s man, Admiral John de Robeck, was astonished by the Allies’ willingness to gratify the “excessive demands” of Venizelos:

[W]e are placing territories overwhelmingly Turkish in population under the rule of the Turks’ secular enemies… [I]t is unthinkable … that the Mussulmans in those areas will peacefully accept Greek annexation… [It will be] the canker for years to come, the constant irritant which will perpetuate bloodshed in Asia Minor probably for generations… M. Veniselos’s deserts vis-à-vis the Entente are great; but is it wise to run the almost certain risk of plunging Asia in blood in order to reward Greece according to the deserts of M. Veniselos, which are very different from the deserts of Greece?[39]

Lloyd George’s close colleagues were full of foreboding. Churchill warned that “the Turkish Treaty means indefinite anarchy,” requiring Greece to fight and dooming Constantinople to a state of siege.[40] Curzon, referencing the alarms of de Robeck and both Ferdinand Foch and the British General Staff (and “an almost complete concurrence of local and expert testimony”) stated that he was “the last man to wish to do a good turn to the Turks… But I do want to get something like peace in Asia Minor – and with the Greeks in Smyrna and Greek divisions carrying out Venizelos’s plan of marching about Asia Minor and fighting the Turks everywhere I know this to be impossible.”[41] As ever, Sir Henry Wilson was apprehensive, but his words of warning made no impression:

Winston [Churchill, Secretary of State for War] and I had an hour with Venizelos this afternoon [19 March]. We made it clear to him that neither in men nor in money, neither in Thrace nor in Smyrna, would we help the Greeks, as we already had taken on more than our small army could do. I told him that he was going to ruin his country, that he would be at war for years with Turkey and Bulgaria, and that the drain in men and money would be far too much for Greece. He said that he did not agree with a word I said.[42]

Fired by a sense of destiny, the Greeks could not imagine that their victorious army might be overcome by the beaten and broken Turks.

At the San Remo Conference in April 1920, the London decisions were confirmed (the main change went to delay a Smyrna plebiscite until five years had passed) and Western Thrace, formerly Bulgarian, was added to Greece’s gains. All the while, however, Kemal’s nationalist forces grew ever stronger in Anatolia. When Venizelos went to London in June, Lloyd George warned him to expect no assistance, given that the Italians disliked the proposed treaty, French public opinion was against military involvement and, he said, his own Foreign Office and military were pro-Turk. Venizelos (“under the fond, admiring gaze of Lloyd George” – Sforza) assured him “that Greece had the necessary force” and “the will” to impose the treaty.[43] Sir Henry Wilson “told Winston that in my opinion we were heading straight for disaster… [O]ur policy had no relation to the forces at our disposal.”[44] While the military men could smell the enemy’s campfires, both Lloyd George and Venizelos remained oblivious to the danger. Immune to doubt, Lloyd George “knew what he wanted but so often wanted the wrong thing,” Vansittart observed. “The higher a man stands the harder it is to get bad ideas out of his head.”[45]

A minor affray at Ismid (İzmit) on 14-15 June 1920 was the first direct clash between Turkish and British soldiers (the latter an outpost of the British occupation of Constantinople). Lloyd George and the French gave the Greeks permission to march out of Smyrna to suppress the Turks. The Greek army took Bursa (onetime capital of the Ottoman Empire) on 8 July and, to secure the position on the other side of Constantinople, occupied Eastern Thrace, entering Adrianople (another former capital) on 26 July. Lloyd George rejoiced in the easy success of the Greeks – “He was right again, it seemed, and the military men wrong, as they so often had been” (Churchill) – praising their fighting ability in the House of Commons on 21 July and underlining their role as the mainstay of stability and order in the region.[46]

The peace terms had been presented to the Turks on 11 May, their protest was rejected, and the Sultan’s representative signed the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 1920.[47] Eastern Thrace and Smyrna were joined to Greece – notwithstanding Turkey’s nominal sovereignty over Smyrna – and the Greek Parliament hailed Venizelos as the “benefactor and saviour of Greece”. The other aspects of the treaty, which dismantled the Ottoman Empire (“Young Keynes had called the wrong treaty Carthaginian”[48]), are beyond the remit of this study, but it should be noticed that its recognition of Armenian independence came after the Soviets had already reconquered part of the republic; by the end of 1920, the Soviets and Turks would, between them, complete the subjugation of Armenia, a boon to the Turks in the coming confrontation with Greece.

The catastrophe

“At last peace with Turkey: and to ratify it, War with Turkey!”[49] Venizelos probably decided for war in October – “with the object of destroying definitely the nationalist forces around Angora [Ankara] and the Pontus”[50] – but he fell from power before the struggle was begun. On 25 October 1920, King Alexander of Greece, bitten on his leg by a pet monkey, died, which meant that the election on 14 November was fought largely on the issue of the return of King Constantine (“Constantine or Venizelos?”). Venizelos was defeated and forced to resign (it was “a great defeat for Lloyd George, as he had put his shirt on the old Greek” – Henry Wilson), and Constantine was recalled (after a plebiscite) to the throne in December.[51] This return of the old friend of Germany put Allied support of Greece in question; as Pavlowitch wrote, “The French and Italians, resenting what they increasingly felt to be a British settlement, used King Constantine’s return as a pretext to come to terms with the new Turkey.” The British decided, in Sir Eyre Crowe’s words, to “stand aloof … waiting to see” how Constantine behaved.[52]

It was Constantine (and War Minister Dimitrios Gounaris, Prime Minister from April 1921) who led the country in the war which the Greeks launched in March 1921 – an initiative that Lloyd George had endorsed, even encouraged, when he spoke to Gounaris in London.[53] The Greeks were held in the spring, as Kemal was now able to field a regular army, but their summer attacks (in July and August 1921) brought them to within 60 kilometres of Ankara – causing Lloyd George again to pour scorn on the naysayers of the War Office.[54] However, the Greeks were exhausted and the Turks regrouped and counterattacked successfully in September. There followed months (September until August) of inaction on the front line, but many things combined to undermine Greece and strengthen Kemal. The Greeks were weakened by political division, financial and economic crisis and collapsing morale among both the soldiers in Asia Minor and the people at home. The Franco-Turkish Agreement (the Ankara Accord) of 20 October 1921 delivered French withdrawal from Cilicia in southern Anatolia (freeing up Turkish forces, and abandoning stocks of weaponry to the Turks), and the last of the Italians left in April 1922. Both the French and the Foreign Office under Curzon (and the War Office) could see no solution other than Greece’s withdrawal from Smyrna and much of Eastern Thrace. Lloyd George, though “still as mad for Greece as ever” (Curzon), offered moral support but not the money and arms that were needed. “Aside from the zealous Prime Minister,” Jensen observed, “the British were not enthusiastic about resharpening the blunted Greek dagger.”[55] Greece’s image in the West could not recover from association with the despised Constantine and reports, most authoritatively from Arnold Toynbee for the Manchester Guardian, of Greek atrocities against Turkish civilians.[56]

The Greeks were further weakened by the removal of forces which some of their more eccentric leaders contemplated using to take Allied-occupied Constantinople.[57] Finally, the Turks went on the offensive and smashed through the Greek line at Afyonkarahisar on 27 August 1922. The Greek front “collapsed like a pack of cards” (Harington), the retreat became a rout and the Turks entered Smyrna on 9 September. The slaughter of civilians began in the city almost immediately, with Armenians suffering even more than Greeks. Vansittart wrote of “butchery at Smyrna… The Turks held a super-massacre of Christians.”[58] Up to 30,000 Christians perished, many brutally murdered, in Smyrna and Aivali during September 1922, and three-quarters of Smyrna, possibly set on fire by Turkish arsonists, was burned to the ground. It was “a human tragedy of gigantic proportions” (Milton).[59] “When the fires died out, Greek Smyrna was no more.”[60] “The Turkish sword had cut the diplomatic knots, and the dream of Greek expansion in Asia was over.”[61]

Constantine abdicated on 27 September 1922 and the Greek army was evacuated from Anatolia with extraordinary speed: “Within a fortnight nothing but the corpses of Greek soldiers remained in Anatolia.”[62] Kemal’s army now threatened Constantinople and the Straits, still garrisoned by British, French and Italian soldiers. Lloyd George was determined to resist, but Sir Henry Wilson urged retreat: “In short, reverse our policy absolutely and make friends with the Turks instead of with the Greeks.”[63] The French and Italians withdrew their men from Chanak (Çanakkale) on the Asian shore of the Dardanelles and in late September there was a tense stand-off there between the Turks and the outnumbered British. In Paris, Poincaré and Curzon agreed, after demented shouting (by Poincaré) and shedding of tears (by Curzon), that the Greeks must also leave Eastern Thrace and that another peace conference would be called to settle the future of Eastern Thrace and Constantinople.[64] The display of brinkmanship at Chanak cooked Lloyd George’s goose: in the Carlton Club on 19 October, the Tory MPs demanded their party’s withdrawal from the coalition government and Lloyd George was forced to resign on 20 October. As Llewellyn Smith put it, “The Greeks and the Turks had done for him at last.”[65] Curzon attributed the “deplorable policy” in favour of Greece entirely to Lloyd George.[66] Typically, Lloyd George blamed not himself, nor Venizelos (“he has never failed his people”), but almost everyone else, including Alexander’s monkey.[67]

Hundreds of thousands of Greeks fled from Anatolia and Eastern Thrace in the months after the Greek defeat in September 1922. A compulsory transfer of populations, agreed by Greece and Turkey at Lausanne in January 1923, exchanged all of the Greek-Orthodox in Turkey (except those in Constantinople) for all of Greece’s Muslims (except, in a quid pro quo for Constantinople, those in Western Thrace).[68] The Treaty of Lausanne in July 1923 – “this abject, cowardly and infamous surrender” (Lloyd George) – was very unlike the five treaties made in Paris: “Hitherto we have dictated our Peace Treaties,” Curzon observed. “Now we are negotiating one with the Enemy, who has an army in being while we have none, an unheard of position.”[69] The Turks regained Smyrna, Eastern Thrace, Constantinople and the Straits (with Turkey guaranteeing freedom of navigation). Out of all that Greece had claimed in 1919, Western (“Bulgarian”) Thrace was the only direct and permanent gain.

Turkey, especially the war zones (and the routes taken by the retreating Greek army), was left devastated and depopulated. She also lost the ancient Greek colonies that were oases of culture and prosperity in Anatolia – “this millenary factor of life and progress in the East”.[70] Greece received “multitudes of destitute, bereaved, and disease-stricken refugees” (Temperley) who, in many cases, eked out an impoverished existence on the fringes of Greek society for decades.[71] It was Lloyd George and Venizelos who brought the Greeks of Asia Minor to destruction with a fearless complacency that history has rightly condemned. They made a treaty which was unenforceable as a result of the recovery of the Turks and demobilisation and growing division and disengagement among the Allies. The French and Americans were unwilling to defend Britain’s ally (or proxy), while many in Britain did not share Lloyd George’s perception of Greece as the guardian of British interests. Greece and the Greeks paid a heavy price for their own ambition and the folly of the statesman, Lloyd George, who adopted their cause and made a peace which, in four short years, turned victory into shattering, irreversible defeat.

[1] David Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties (London, 1938), II, 1202.

[2] Western Thrace was part of Bulgaria, another of Germany’s allies. See ‘Neuilly’.

[3] This phenomenon is marvellously evoked in Margaret MacMillan, Peacemakers: The Paris Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War (London, 2001), 363. Arnold Toynbee, more knowledgeable than the politicians, rejected the idea that “the Modern Greek” was in any sense “a scion of Ancient Hellenic society”. Arnold J. Toynbee, The Western Question in Greece and Turkey: A Study in the Contact of Civilisations (London, 1922), 334-46.

[4] E.L. Woodward and Rohan Butler, eds., Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939 (London, 1956), First Series, Vol. XII, 551, Memorandum by Nicolson, 20 December 1920 (hereafter DBFP). Michael Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor 1919-1922 (London, 1973), 84.

[5] Harold Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919 (London, 1933), 35.

[6] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, 11, Leeper’s Diary, 3 February 1919; ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 3 February 1919.

[7] Ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 4 February 1919.

[8] Ibid., 3/9, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 8 February 1919.

[9] Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 271, Nicolson to Lord Carnock, 25 February 1919.

[10] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, 17, 41, 68, 71, Leeper’s Diary, 25, 26 February, 21 May, 3 July, 22 August, 2 September 1919; ibid., 3/8, Leeper to Rex Leeper, 26 February, 22 May, 20 June 1919; ibid., 3/9, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 6 July 1919. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 255-56, Diary, 3, 4 February 1919.

[11] Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties, II, 1204.

[12] “He [Venizelos] was a courteous fox, an affable barmecide of reason, the best foul weather friend we ever had, benign and transparent beneath a black skull-cap. Invincible eyes glinted behind his glasses. I admired and distrusted him immensely.” Lord Vansittart, The Mist Procession: The Autobiography of Lord Vansittart (London, 1958), 217.

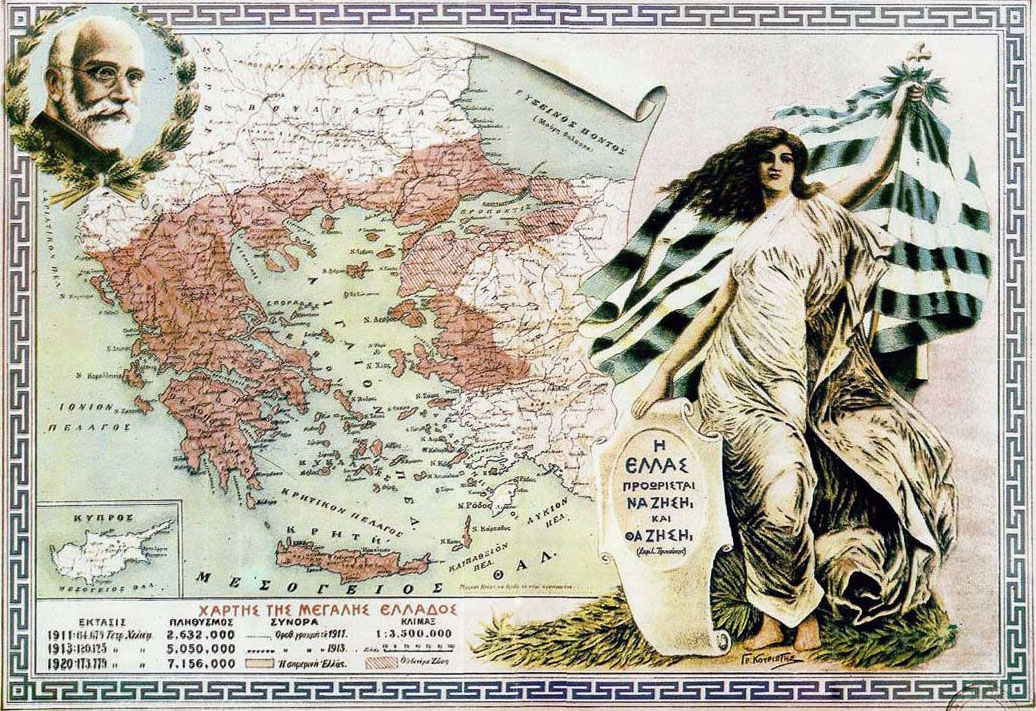

[13] “Hellenism and the Principles of President Wilson”, National Archives MFQ 1/391/1, 189. The Sphere, 1 March 1919, map by George Soteriadis.

[14] Foreign Office Papers, FO 608/93, 349, Hardinge to Balfour, 2 April 1919. Paul C. Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919-1920 (Columbus, Ohio, 1974), 94. N. Petsalis-Diomidis, Greece at the Paris Peace Conference (1919) (Thessaloniki, 1978), 196, 200-1.

[15] FO 608/103, 159, Webb to Foreign Office, 29 April 1919; ibid., 162, Forbes to Riddell, 29 April 1919.

[16] Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States: The Paris Peace Conference 1919 (FRUS), V, 422, Council of Four, 2 May 1919. Paul Mantoux, The Deliberations of the Council of Four (Princeton, 1992), I, 454, 2 May 1919.

[17] FRUS, V, 465-68, 5 May 1919. Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, I, 482-85, 5 May 1919.

[18] FRUS, V, 482-84, Council of Four, 6 May 1919. Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, I, 494-96, 6 May 1919. See also FO 608/89, 260, Hankey to Balfour, 6 May 1919.

[19] FRUS, V, 484, Council of Four, 6 May 1919. “Now you have got Smyrna.” FO 371/3599-168801, Talbot’s report on Greek negotiations at the Peace Conference, December 1919.

[20] FO 371/3593, 273, Granville to Curzon, 3 December 1919. Papers of Frances Stevenson, FLS/4/11, 129, Diary, 9 May 1919. Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision, 80, citing Venizelos’s Diary. See also Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 327, Diary, 6 May 1919.

[21] C.E. Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, His Life and Diaries (London, 1927), II, 190, Diary, 7 May 1919.

[22] FRUS, V, 501-4, Council of Four, 7 May 1919; 553-58, 10 May 1919; 570-1, 577-8, 12 May 1919. Mantoux, Deliberations of the Council of Four, I, 505-7, 7 May 1919; II, 29-32, 36-42, 47-9, 10, 11, 12 May 1919.

[23] Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, II, 189-90, 191-92, Diary, 6, 10, 11 May 1919. See also Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres, 105n58, citing Bliss Papers, Box 65, Diary, 5 June 1919. “Madness and not yet midsummer!” was Vansittart’s verdict. Vansittart, The Mist Procession, 217.

[24] FO 608/104, 7, note by Vansittart, 20 May 1919. FRUS, IX, 47-50, Heads of Delegations, 8 November 1919, Report of the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry on the Greek Occupation of Smyrna and Adjacent Territories. Giles Milton, Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922: The Destruction of Islam’s City of Tolerance (London, 2008), 142-48.

[25] Winston Churchill, The World Crisis: The Aftermath (London, 1929), 367-68.

[26] FRUS, VI, 729-30, Council of Four, 27 June 1919. See also Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson (Princeton, 1989), Volume 61, 238, 253, Diaries of Dr Grayson and Ray Stannard Baker, 27 June 1919; ibid., 240, 246, Notes of a Press Conference, 27 June 1919.

[27] Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 62, 141, Wilson to Lansing, 4 August 1919; ibid., 428, Memorandum by Lansing, 20 August 1919.

[28] FO 371/3593, 187, note by Curzon, 19 October 1919.

[29] FRUS, IX, 36, 44-73, Heads of Delegations, 8 November 1919, Report of the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry on the Greek Occupation of Smyrna and Adjacent Territories. This was restated in the Council’s letter to Venizelos. Ibid., 131-33, Note to Venizelos.

[30] Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, II, 213, Diary, 28 October 1919.

[31] The British had only small garrisons in Anatolia, mostly at key points in the railway system, while Greek, Italian and French soldiers occupied the west and south (the French in Cilicia).

[32] Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties, II, 1285.

[33] FO 608/112, 716, Webb (for Robeck) to Curzon, 10 October 1919. Venizelos made the same point. Lloyd George Papers, F/55/1/26, Venizelos to Lloyd George, 27 October 1919; ibid., F/92/12/5, Note of an interview between Lloyd George and Venizelos, 31 October 1919.

[34] FO 608/112, 662, note by Vansittart, 30 August 1919.

[35] Ibid., 661, note by Vansittart, 1 September 1919. On Vansittart’s first note, Balfour’s secretary wrote, “Mr Balfour does not think he can do anything in this direction.” On his second, “I expect Mr Wilson quite realises the consequences of his delay” – beside which Balfour wrote “Yes”.

[36] French Foreign Minister Stephen Pichon at a meeting with Curzon on 12 November. FO 371/4239-151671, Memorandum by Curzon, 12 November 1919 (also in Curzon Papers, F/112/278).

[37] Records of the Cabinet Office, CAB 23/20/1, 30, A note of dissent by Lord Curzon, 7 January 1920. DBFP, First Series, VII, 44-50, 56-60, 68-71, Notes of the Allied Conference, 14, 16 February 1920. Westermann put the Sultan’s position well: “He still rules there [Constantinople] – or, better, is ruled there.” Isaiah Bowman in E.M. House and C. Seymour, eds., What Really Happened at Paris: The Story of the Peace Conference, 1918-1919 by American Delegates (London, 1921), 177.

[38] DBFP, First Series, VII, 54-60, 65-68, 121-22, 127, 186-90, 219-20, 226-34, 238-39, 511-14, 517-20, Notes of the Allied Conference, 14, 16, 18, 21, 24, 25 February, 16 March 1920.

[39] Reaction of the High Commissioners: Paraphrase of a telegram from the British, French and Italian High Commissioners, 10 March 1920, in DBFP, First Series, VII, 500; ibid., XIII, 17-19, Robeck to Curzon, 9 March 1920 (also in Curzon Papers, F/112/278 and Lloyd George Papers, F/206/4/17). The American High Commissioner, Mark Bristol, issued a similar warning. Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres, 286n12.

[40] Churchill to Lloyd George, 24 March 1920, in Churchill, The Aftermath, 377-78. This was billed as “The March of Facts”.

[41] Lloyd George Papers, F/12/3/24, Curzon to Lloyd George, 9 April 1920. Sir Maurice Hankey produced a superb analysis of divided opinion in Britain’s political and military leadership. Hankey Papers, 1/5, Diary, 27 March 1920. See also Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 3/11, Leeper to Alexander Leeper, 18 February 1920.

[42] Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, II, 230, Diary, 19 March 1920. The formal minutes of the meeting are in the Lloyd George Papers, F/199/9/2, Notes of a Conversation, 19 March 1920.

[43] Venizelos to Foreign Ministry, 15 June 1920, in Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision, 124, citing X. Stratigos, Greece in Asia Minor, 111-12. Count Carlo Sforza, Fifty Years of War and Diplomacy in the Balkans (New York, 1940), 164.

[44] Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, II, 243-45, Diary, 15, 16, 17 (quoted), 20, 24 June 1920.

[45] Vansittart, The Mist Procession, 246-47.

[46] Churchill, The Aftermath, 376. Parliamentary Debates, Fifth Series, Volume 132, 477-80, 21 July 1920. See also Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 66, 47, Lloyd George to Wilson, 5 August 1920.

[47] The treaty was also signed by Britain, France and Italy, but no American representative attended.

[48] Vansittart, The Mist Procession, 252.

[49] Churchill, The Aftermath, 376. Venizelos “grasped at such excessive territorial prizes that he failed to secure the greater prize of peace”. Toynbee, The Western Question in Greece and Turkey, 64.

[50] DBFP, First Series, XIII, 157, Venizelos to Lloyd George, 5 October 1920.

[51] Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, II, 269, Diary, November 1920.

[52] Stevan K. Pavlowitch, A History of the Balkans, 1804-1945 (London and New York, 1999), 238. DBFP, First Series, XII, 514, 550, Memoranda by Nicolson, 20 November, 20 December 1920, with notes by Crowe and Curzon, 20 December 1920.

[53] DBFP, First Series, XV, 451, Proceedings of the Third Conference of London, 18 March 1921. Michael L. Dockrill and J. Douglass Goold, Peace without Promise: Britain and the Peace Conferences, 1919-23 (London, 1981), 218-19.

[54] Montagu Papers, MSS EUR/D523/13, Montagu to Reading, 1 September 1921. Lloyd George to Worthington-Evans, 21 July 1921, in Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision, 226. “A new Greek Empire will be founded, friendly to Britain and it will help all our interests in the East…” Papers of Frances Stevenson, FLS/5/9a, Diary (relating Lloyd George’s view), 20 July 1921.

[55] Hardinge Papers, 44, 295, Curzon to Hardinge, 24 December 1921. Peter Kincaid Jensen, ‘The Greco-Turkish War, 1920-1922’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Volume 10, No. 4 (November 1979), 561.

[56] Milton, Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922, 198-202.

[57] General Sir Charles Harington, Tim Harington Looks Back (London, 1940), 109-10. Michael M. Finefrock, ‘Atatürk, Lloyd George and the Megali Idea: Cause and Consequence of the Greek Plan to Seize Constantinople from the Allies, June-August 1922’, Journal of Modern History, Volume 52, No. 1 (March 1980), 1057-66.

[58] Vansittart, The Mist Procession, 289-90. Harington, Tim Harington Looks Back, 110.

[59] Milton, Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922, 285. Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917-1943 (London, 2016), 3, 242 (12-30,000). Pavlowitch, A History of the Balkans, 238, “tens of thousands”. Richard Clogg, A Short History of Modern Greece (Cambridge, 1986), 118 (30,000).

[60] MacMillan, Peacemakers, 462.

[61] H.W.V. Temperley, ed., A History of the Peace Conference of Paris (London, 1921), VI, 37.

[62] Harold Nicolson, Curzon: The Last Phase 1919-1925: A Study in Post-War Diplomacy (London, 1934), 270.

[63] Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, II, 313, Wilson to Curzon, n.d..

[64] David Gilmour, Curzon: Imperial Statesman 1859-1925 (London, 1994), 543-48. See also David Walder, The Chanak Affair (London, 1969), 187 et passim.

[65] Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision, 318.

[66] FO 839/8, Telegram no. 94, Curzon to Bonar Law, 9 December 1922.

[67] Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties, II, 1227-8, 1341-62.

[68] Adding together the Greeks who fled after the military defeat – about 1 million – and those who moved under the population exchange, at least 1.2 million refugees entered Greece from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace, while about 400,000 Muslims (100,000 in 1922, plus 300,000 under the treaty) were expelled into Turkey.

[69] Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties, II, 1351. D’Abernon Papers, Add MS 48925A, 114, Curzon to D’Abernon, 20 December 1922. The Turks “are coming, not hat in hand, but with a victorious army behind them. That makes a lot of difference…” Joseph C. Grew, Turbulent Era: A Diplomatic Record of Forty Years, 1904-1945 (London, 1953), I, 486, Grew to Margaret Perry, 13 November 1922.

[70] Sforza, Makers of Modern Europe, 169.

[71] Temperley, History of the Peace Conference, VI, 107. Lloyd George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties, II, 1234, 1243. Hugh Seton-Watson, Eastern Europe Between the Wars, 1918-1941 (Cambridge, 1946), 276.