Albania was one of two small Balkans countries, the other being Montenegro, which did not have its future settled by any positive decision made at the Peace Conference. Most delegates considered Albania to be important only because it was one of the keys to settlements with Italy, Yugoslavia and Greece. In particular, it was deemed to have a significant part to play in resolving the Adriatic question. Much more than Montenegro, Albania was used as a pawn and its people were not regarded as a nation with aspirations that had to be taken into account. Its survival as an independent state was secured by the efforts of Albanians themselves and owed nothing to the peacemakers in Paris.

The people of Albania endured centuries of Ottoman rule having been conquered by the Turks in the 15th century. Islamisation followed, with most of the population becoming Muslims, but Christian minorities survived, Greek Orthodox in the south and Catholics in the north. The 19th century brought the first efforts to achieve automony, and the defeat of the Ottomans in the First Balkan War in 1912 caused Albanian leaders to aspire to independence for the first time. After the entry of Serbian, Montenegrin and Greek forces – they “fell upon Albania with invasions, oppressions and ferocious massacres”[1] – the Albanians issued a declaration of independence in November 1912. Though recognised by the Powers, the country broke up in 1914 as tribal and ethnic groups (including the Greeks of northern Epirus) rebelled or fought each other, with the encouragement of “the greedy neighbours, the Serbians and the Greeks”.[2] The disintegration of Albania at this time seemed to observers to confirm the idea that Albanians lacked the national consciousness to constitute a nation-state.

In 1914-15, the armies of Greece, Serbia and Montenegro again entered the country – they “invaded Albania anew and martyrized it”[3] – and Italy seized the port of Valona (later Vlorë), the Gibraltar of the Adriatic. The Italians were promised Valona and a protectorate over a reduced, central-Albanian state (the Muslim part) in the Treaty of London of 1915, but the Austro-Hungarians invaded later in 1915 and held most of Albania until the Allied offensive of September 1918, when the Italians advanced and occupied most of the country.[4]

The Greek Committee

In 1919, the contest between Serbia (or Yugoslavia) and Italy over northern Albania was an extension southwards of their dispute in the Adriatic question. The Serbs regarded northern Albania as part of “Old Serbia” and claimed territory as far south as the Drin river valley. They wanted to exclude the Italians from Albania, to prevent, as Nicola Guy put it, “the bizarre and dangerous situation of being bordered by Italy on both their northern and southern frontiers”.[5] The Drin led to Lake Scutari, which was connected to the sea by the Boyana, so the Yugoslavs’ securing of northern Albania would provide an outlet on the Adriatic, something that the Italians were keen to deny them. The Italians had similar concerns in the south, where the acquisition of northern Epirus would give Greece control of the Corfu Straits – the narrow channel between Corfu and the mainland – and this would allow Greece to dominate the entrance to the Adriatic (the Otranto Straits). So, the Italians wanted their protectorate “as large, north and south, as possible” – to minimise the gains of both Serbia and Greece.[6]

The French, British and even the Americans were prepared to use Albania as a source of bargaining chips for the conciliation of Italy, Yugoslavia and Greece. Albanian interests and self-determination were of secondary (for the Americans, and sometimes the British) or no (for France, and often Britain) importance. Nicola Guy has made the astute observation that “the great powers did not initially deem the Albanian question to be a national question at all, but instead equivalent to a colonial problem, in areas not yet ready for independence” – but the Allies were to show an awareness of regional concerns (the views of neighbours) that was hardly typical of their thinking on colonial affairs.[7]

The British proposed to give Italy a protectorate over central Albania as “an inducement to her to relinquish [to Yugoslavia] some of her pretensions on the Dalmatian coast” – and they thought that allowing Italy to annex Valona would make it easier to argue that Italy did not require Fiume and the ports of Dalmatia. Nicolson and Leeper also held that the inhabitants of southern Albania should be “allowed to opt for inclusion in Greek territory” – but the northern Albanian frontier, where Serbia hoped to expand, “should remain unchanged”.[8] The American Inquiry report of 21 January 1919, citing the “weakness of national feeling among the people”, declared that “the project of a united Albania appears impracticable”: Greece should receive northern Epirus in the south, while northern Albania might be joined to the Albanian parts of Serbia and Montenegro in “a self-governing unit under Jugo-Slavia as a mandatory of the League of Nations”. But Italy should be “excluded” entirely “because of the sharp feeling against her in both Greece and Jugo-Slavia”.[9] It is striking that the likely reaction of other peoples and states was cited even by the Americans, rather than the wishes of Albanians.

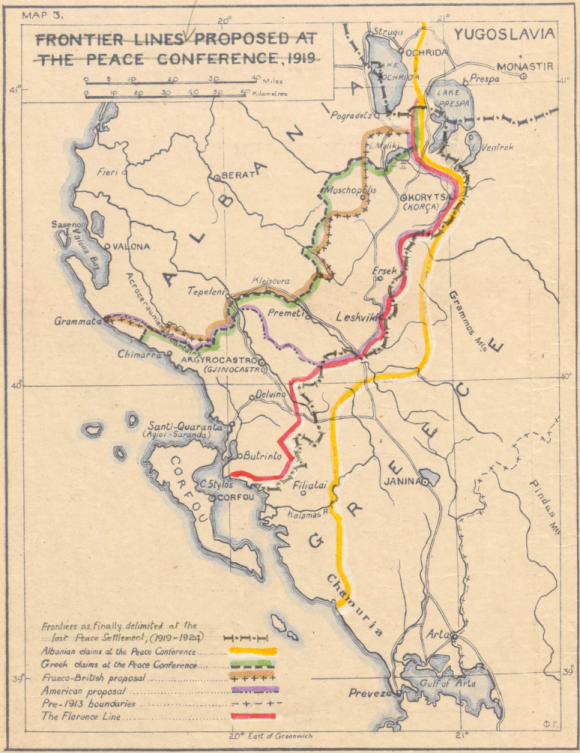

Thus, to the animosities and conflicting claims of Albania’s neighbours was added the complication that the British and American starting positions were quite far apart. The neighbours proceeded to present their demands in Paris. Greece’s first formal submission, Prime Minister Venizelos’s paper of 30 December 1918, claimed that there were 120,000 Greeks and only 80,000 Albanians in northern Epirus (including Koritsa, inland), and that, although “a substantial portion of this Greek population uses Albanian as its mother tongue,” the decisive criterion had to be “national consciousness”: “those Greeks in Northern Epirus have formed part of the Greek family for centuries.”[10] When Nicolson met Venizelos on 15 January, the Greek leader was “particularly firm on the question of Koritza”.[11] On 26-27 January, Nicolson wrote (and Sir Eyre Crowe revised, his tone tending to favour the Greeks) a “summary and commentary” on Venizelos’s claims. It spoke of the “justified” Greek claim for northern Epirus – except regarding Koritsa, which was “predominantly Albanian” – “in respect to which, nevertheless, some concession to Greece may have to be made” (Crowe’s phrase).[12] The British War Office supported the Greek claim for Koritsa on the grounds that the major road that ran through it to Salonica was economically and militarily vital to Greece.[13]

In his appearance before the Council of Ten on 3 February, and again at the Commission for the Study of Territorial Questions Relating to Greece (the Greek Committee), the charismatic Venizelos succeeded in lighting up the room and charming his allies.[14] The Greek case encountered mixed fortunes in the Committee, however. All except Italy gave the south (most of northern Epirus) to Greece; the French and then the British (with Crowe rejecting Nicolson’s advice) also gave Koritsa to Greece, but the Americans, citing the ethnicity of the majority, insisted that it must be part of Albania.[15] Venizelos modified the Greek claim with a line that differed only marginally from the French proposal, but American and Italian opposition to Greece’s having Koritsa proved insuperable. On 4 March, America’s Clive Day said that they could not give Koritsa to Greece because “the majority of the population” there “is in favour of Albania”. Crowe, on the other hand, cited economic and strategic considerations to explain his coming down firmly in support of the Greek claim:

After having heard Mr. Venizelos’ explanations, I understand that there is in these regions an Albanian element very important as to number, but that we must not be guided altogether by ethnic reasons… I do not feel absolutely certain that we know precisely the desires of the population; but, putting aside this consideration, admitting even that the population does not desire to be united to Greece, I think that there are much more cogent reasons than this, economic and strategic reasons, which should guide the commission. In fact, the high road which leads from the lakes [Prespa and Ohrid] to the sea is not absolutely necessary to the economic life of northern Albania, but it is absolutely necessary to southern Albania, where the Greeks are in the majority. I wish also to call your attention to the great power of assimilation possessed by the Greeks.[16]

Italy was still expected to gain the Albanian protectorate, as promised in the Treaty of London, and it is ironic that the Power opposed to that self-serving treaty, the United States, was fighting for the big Albania (including the south) that would have maximised Italy’s sphere of influence – while Britain and France, though honouring their commitment, opted for small Albania because giving it to Albania “will probably be to hand it over to Italy”.[17] Despite Nicolson’s efforts to find a compromise, the Greek Committee was deadlocked, presenting three separate recommendations, with Koritsa the main bone of contention.[18] The Albanian National Committee, based in Geneva, “expressed its gratitude to the American delegates for their noble defense of Albania’s right to Koritza” and urged the Americans to accept a League mandate to govern Albania.[19] Albania’s principal enemy, Venizelos, offered to renounce his claims if America took the mandate. He surely knew there was “no question of an American mandate over Albania” (Crowe) and was intent on presenting the face of a man of reason and moderation. He would have been pleased to hear that Crowe, rather unfairly in view of the wide difference between the Americans and the French and British, blamed the Italians for the lack of progress: “Italy stands in the way of any settlement at present.”[20]

Two versions of the lines presented at the Greek Committee.[21]

The Albanians

Yugoslavia’s claim to northern Albania was formally submitted in mid-April, when Andrija Radović, the leading pro-Yugoslavia Montenegrin, presented a memorandum demanding 3,600 square kilometres around Scutari (Shkodër) and on the north bank of the Drin.[22] Given Radović’s denunciation of Albanians as abettors of Ottoman oppression, his endorsement of an Albanian state – “We sincerely wish for the creation of an independent Albania”[23] – might seem surprising, but the Yugoslavs preferred a weak Albania to a potentially menacing Italian protectorate. Knowing that the latter was likely, however, the Yugoslavs demanded northern Albania “as a set-off against an Italian protectorate over the central and southern portions”.[24] This was their priority, despite the talk of ethnic brotherhood with the supposedly “lost Serbs” of northern Albania. Serbia and Montenegro had already, before 1914, acquired the areas of greatest historical and emotional significance, notably Kosovo, so the fate of northern Albania necessarily featured low in the Serbian (and Yugoslav) scale of priorities, which was led by the conflicts over the Banat and Fiume and the difficulties in Montenegro.

The peacemakers initially showed no interest in hearing an Albanian voice. Shunning one approach, Crowe held that, “We know all that we want to know about Albania…”[25] Discussing the lack of “official Albanian representation” at the Conference, he wrote: “Confidential. In practice the Italian Delegates here are making themselves, almost officially, the mouthpiece of the most extreme Albanian claims, so that there is no danger whatever of Albanian interests being neglected.”[26] The country which coveted Valona and a protectorate was seen to be representing Albania! Albania’s standing in Paris resembled, to a degree, that of defeated enemy countries. Because the Peace Conference did not recognise Albania as an independent state, she had no official delegates; British friends bemoaned the fact that “today, when we have admitted the principles of open diplomacy and justice for the weak, one nationality, and that the weakest, should be refused a hearing.”[27]

Albania did have a government of sorts, chosen at a meeting in Durazzo (Durrës) in December 1918. It was not recognised by any of the Powers and, with the country occupied by foreign armies, and given the Albanians’ traditional disregard for any form of authority outside the tribal structures, this was scarcely a government at all. Nevertheless, its representatives were permitted to go Paris. A written statement of claims was submitted by Prime Minister Turkhan Pasha on 12 February. Crowe considered the paper “hardly worth reading”. Nicolson was adamant that Albania’s unwise demand for part of southern Epirus, allocated to Greece back in 1913, was “inadmissible” and he commented that, “Their claims are fantastic, & even the Italians do not propose that Albania should annex what is now Greek territory.” He would give some parts of Montenegro to Albania, but all the proposed transfers from Serbia (including Prizren and Pristina in Kosovo) were also deemed “inadmissible”.[28]

On the ethnographical map submitted by the Albanians on 12 February 1919 (right), the Albanian-majority areas included all of Epirus (Tchameria) and substantial parts of Serbia and Montenegro.[29] Turkhan Pasha was heard by the Council of Ten on 24 February, or, rather, by the Foreign Ministers, for the heads of government did not attend. Invoking “the principle of nationality so clearly and solemnly proclaimed by President Wilson and his great Associates,” he demanded all of the Albanian territories (“the return of brother Albanians to the Albanian family”) that newly independent Albania had failed to gain in 1913 when “the unjust claims of our neighbours” were preferred.[30] Nicolson’s diary entry showed how little regard the Council had for “old” Turkhan as he “drones into his henna-dyed beard. The Ten chatter and laugh while this is going on. Rather painful.”[31] He was similarly dismissive – “Turkhan was particularly pitiable” – when the Albanians appeared before the Greek Committee on 27 February. Turkhan stretched the credulity of his audience by introducing his delegation as “a pure representation of the entire people of Albania” and his colleague from Koritsa (Tourtoulis) made the ridiculous claim that “throughout the whole country which the Greeks call Northern Epirus and which we call Southern Albania, there was not a single Greek” and spoke of “the Albanian majority” in southern Epirus.[32]

On the ethnographical map submitted by the Albanians on 12 February 1919 (right), the Albanian-majority areas included all of Epirus (Tchameria) and substantial parts of Serbia and Montenegro.[29] Turkhan Pasha was heard by the Council of Ten on 24 February, or, rather, by the Foreign Ministers, for the heads of government did not attend. Invoking “the principle of nationality so clearly and solemnly proclaimed by President Wilson and his great Associates,” he demanded all of the Albanian territories (“the return of brother Albanians to the Albanian family”) that newly independent Albania had failed to gain in 1913 when “the unjust claims of our neighbours” were preferred.[30] Nicolson’s diary entry showed how little regard the Council had for “old” Turkhan as he “drones into his henna-dyed beard. The Ten chatter and laugh while this is going on. Rather painful.”[31] He was similarly dismissive – “Turkhan was particularly pitiable” – when the Albanians appeared before the Greek Committee on 27 February. Turkhan stretched the credulity of his audience by introducing his delegation as “a pure representation of the entire people of Albania” and his colleague from Koritsa (Tourtoulis) made the ridiculous claim that “throughout the whole country which the Greeks call Northern Epirus and which we call Southern Albania, there was not a single Greek” and spoke of “the Albanian majority” in southern Epirus.[32]

Albania’s cause was not aided by the arrival of an Albanian leader who was probably willing to concede territory in the north in return for Yugoslav sponsorship of his bid to control the rest of Albania. Essad Pasha Toptani, uncle of the future King Zog, was an ambitious and unscrupulous chieftain who had forced the Albanian Senate, at gun-point, to proclaim him President of the Albanian Cabinet in October 1914. He fled to Rome and Paris in 1916 (after the Austrian invasion) and, loyal to the Allies, was received as Albania’s head of government. He never accepted the legitimacy of Turkhan’s government and delegation and, styling himself “The President of the Albanian Government”, he asked in January 1919 if he could send a representative to Paris to be the voice of Albania; Nicolson’s advice was “No acknowledgement. (Essad is unrepresentative and a scoundrel.)”[33] In March 1919, he returned to Paris and proceeded to present ideas on an Albanian settlement (with Essad himself recognised as President). The leaders of organisations representing the Albanian “colonies” in Turkey, America and Romania protested that Essad possessed “no mandate from the Albanians of the mother country or of the colonies” – causing Nicolson to remark that, “Here we have a Turk, an American and a Frenchman [the Romanian] all signing a document to say that Essad (who after all is an Albanian) does not represent Albania. And apart from this we have the “official” Albanian Delegation (Turkhan Pasha, etc.) who say that they and they only are the mandatories of their country. It is hopeless!” For Crowe, writing on 10 April, the problem went deeper, to the lack of fitness of Albanians to govern themselves:

It has been the mistake of all our pro-Albanians to close their eyes to the fact that “Albania” is a congeries of tribes all divided by ancient feuds and vendettas among themselves, all equally unscrupulous in the pursuit of these feuds and quite incapable of government. If there is to be an Albanian State it must be under the protectorate of a European Power. Italy wants to have that protectorate. I am in favour of agreeing to this; but our consent ought to be made subject to conditions: the Italians should relinquish to Greece and Serbia those territories in the south and in the north east which in Italian hands would remain a standing military menace to Greece and Serbia. Italy should moreover not receive an Albanian mandate except as part of a settlement of the Adriatic question satisfactory to the allies, especially as regards Fiume.[34]

Turkhan Pasha had problems within his delegation as well. He proposed on 14 April that an unpartitioned Albania should be established. In a separate letter, Mehmed Konitza’s and Mihal Tourtoulis’s demand for “la complete independence de l’Albanie” differed from Turkhan’s vague talk of “autonomy”, but their main purpose (and the main contrast with Turkhan) was to attack Italy. They catalogued the history of “encroachments of Italy in Albania” and warned that Italy’s acquisition of Valona and a protectorate would lead to violent resistance. Like Turkhan, they proposed asking a Power to “guide Albania in the first steps of its political life” – but they suggested the United States and made it clear that Italy (and any other state with interests in the Balkans) need not apply.[35] Nicolson commented,

This is a curious and interesting document, in that it represents a revolt on the part of the Albanian Delegation against their Italian masters.

It is curious that the document is not signed by Turkhan Pasha, but by Mehmed Bey Konitza – his second in command.

It is clear that the Albanian Delegation, realising that Italy is not a popular figure in Paris or in the Balkans, wish to disassociate themselves from the Italian connexion.[36]

America’s Stephen Bonsal reflected the disarray among the Albanians when he noticed a petition which indicated that they “want Italian protection but nevertheless are violently opposed to an Italian protectorate!”[37] Another Albanian call for an American protectorate prompted Nicolson to remark tiredly, “I much doubt whether the U.S. will accept an Albanian mandatory. I wish they would!”[38]

April and May saw a profusion of proposed solutions for Albania; one, formally presented by Nicolson but initiated by the indefatigable Leeper, would have made Koritsa “the seat of a Central Albanian University under United States protection”.[39] All involved some form of partition and none would have created a united, independent Albania. The British were determined to protect Greek interests: commenting on the Tardieu Plan for the Adriatic on 29 May, Crowe hoped that the “extent and nature” of the projected Italian protectorate in Albania would become “the subject of a bargain in which the allies should be able to obtain reasonable satisfaction for Greek claims, both in Northern Epirus and the Dodecanese.”[40] The shadow of Lloyd George loomed large. His patronage of Venizelos and Greece was long established, and he began in April 1919 to work at finding a settlement – any settlement at any price – between Italy and Yugoslavia. Satisfying the Yugoslavs and Italians would be the main thrust of any agreement and Albanian aspirations became even less important.

Press reports of the partition-and-protectorate intentions of the Conference brought a storm of protest from Albanians and Turkhan Pasha addressed a passionate appeal to Clemenceau on 5 June:

Following the persistently circulating news about the resolution of the dispute between Italy and Yugoslavia, the Albanian Delegation feels obliged once more to protest respectfully against the way in which the Albanian question is being handled by the Conference.

[T]he Albanian Delegation has presented to the High Conference the legitimate claims of its country and has waited in vain until now for them to be considered. It finds instead, with the greatest regret, that the Albanian question has never come under specific scrutiny but, on the contrary, that Albania has always been considered as a source of compensations to facilitate the regulation of conflicts which are completely foreign to our people, or even to satisfy the unjustified covetousness of her neighbours. Thus, the Commission on Greek affairs has discussed and even seriously envisaged the annexation of a large part of southern Albania to Greece… In the same way, when the Peace Conference is attempting to define the position of Italy on the eastern seaboard of the Adriatic, it is only concerned with Albania incidentally, in order to facilitate the solution of the Italo-Yugoslav dispute. It is solely to resolve this question that the Conference has sought to give Italy the mandate over Albania as well as possession of the port of Valona…[41]

This remarkable letter was a cogent, powerful exposition of the scandalous treatment of Albania, reduced to being an expendable pawn, a “source of compensations” to resolve disputes between her neighbours and satisfy their “unjustified covetousness”.

Failure to settle

Turkhan Pasha’s words might have had an influence on Wilson, perhaps reminding him of his exhortation in 1918 against the bartering of peoples like “chattels and pawns in a game”.[42] But he was also motivated by annoyance with the Italians. The breach between Wilson and Italy over the Adriatic question, featuring his famous statement of 23 April and the furious Italian reaction, caused Wilson to question the idea of conciliating Italy at the expense of Albania. In the Council of Four on 6 May, he acknowledged Albanian hostility to an Italian protectorate and said that “they must be allowed their independence” (to which Lloyd George replied that he did not “really know what they would do with it, except cut each other’s throats”).[43] Writing to Secretary Lansing on his way back to America in July, Wilson voiced his “very profound interest in the fortunes of Albania. I am fearful lest midst the multitude of other things that might seem more pressing and important, due consideration of those rights should be overlooked. I beg that you will be very watchful concerning them.”[44] This attitude was echoed in Paris when Nicolson urged that Albania should cease to be used as “an item in the general give-and-take of an Adriatic settlement” in its capacity as “a further pawn for inducing Italy to abandon her claims elsewhere”.[45]

In the event, however, despite Wilson and Nicolson, Albania was very much part of the ongoing attempt to resolve the Adriatic question. After Tittoni, Italy’s new Foreign Minister, held out in his July proposals for Valona and a mandate over most of the rest of Albania, America’s Henry White favoured compliance in return for Italy’s allowing Dalmatia to go to Yugoslavia.[46] Greece and Italy then conspired to share the spoils. The Tittoni-Venizelos Agreement of 29 July 1919 saw Tittoni agreeing to support the Franco-British line in southern Albania, giving Greece Koritsa as well as Argyrocentro, and Venizelos accepting Italy’s acquisition of Valona and the Albanian mandate.[47] But Tittoni was not keen to battle with the Americans to acquire Koritsa for Greece: in his paper on the Adriatic question on 29 August, he conceded Argyrocentro to Greece but left Koritsa in Albania, explicitly identifying this as the proposal of the American delegation.[48] The Agreement of 29 July could not mask the continuing conflict of interest between Italy and Greece.

Lloyd George, Clemenceau and Frank Polk all pressed Wilson to accept the Valona-and-mandate award to Italy in order to facilitate an Adriatic settlement and, in mid-September, needing to grasp the nettle (“time is of the essence”), Wilson finally gave way and approved the Italian mandate.[49] Albanian independence was preserved by the failure to agree on other issues: the mandate was conditional (in effect) on Italy’s acceptance of the loss of Fiume, which d’Annunzio’s seizure of that city on 12 September, greeted rapturously in Italy, made a political impossibility for the Italian government. The Yugoslavs, moreover, were not willing to accept Italy’s gaining control of Albania.[50] They were moving away from the Serbian ambition to take northern Albania and beginning instead to prefer Albanian independence, or some form of internationalisation, in order to close out the Italians. However, soon after the Italian mandate was conceded by Wilson, the Yugoslav claim for northern Albania was revived, Vesnić emphasising “les liens de sang” which united its people and the Serbs.[51]

Albanian feelings counted for nothing. Anti-Italian (and anti-Yugoslav) sentiment in Albania, featuring a “besa” (oath of peace) between some Albanian tribes, caused Leeper to acknowledge that, “The strength of Albanian feeling against an Italian mandate is not negligible. The Albanians dislike & despise the Italians & since the Tittoni-Venizelos agreement & Tittoni’s speech in Parliament [announcing the agreement] have lost all confidence in them.” But he considered Albanian independence “hardly practical politics” and expressed his “grave doubts” about encouraging the Albanians “at a moment when, rightly or wrongly, HMG have shown the Italian Govt. every readiness to support an Italian mandate for Albania”.[52] An Albanian protest prompted Leeper’s observation that, “Unfortunately there is no serious alternative to the Italian mandate &, much as they dislike the idea, even the Americans now realise this.”[53] General Phillips’s desire to encourage Albanian opposition to the Italians and Serbs led the Foreign Office’s Lancelot Oliphant to comment that “after his long stay [at Scutari] he is apt to regard Albania as the hub of the universe and as being more important than in fact it is” – an interesting restatement of Albania’s role as pawn.[54]

The joint declaration of 9 December 1919, the Adriatic plan agreed by the British, French and Americans, proposed that Italy should have Valona “in full sovereignty” and a League of Nations mandate “for the administration of the independent State of Albania” – these words reflecting the idea of a temporary arrangement – and offered a detailed draft of the terms of the mandate. Yugoslavia was denied territorial gains in the north but was to be given the right to construct and operate a railway line to Scutari. Greece was to occupy southern Albania according to the American line in the Greek Committee (that is, not including Koritsa) pending “later negotiation between the three Allied representatives [Britain, France and America] on the one hand and Italy and Greece on the other, the three Allied representatives acting for Albania.”[55] Albanians were not to be asked to represent Albania.[56]

This was as close as the Peace Conference got to an Albanian settlement. Allied unity did not last long, shattered by the Anglo-French Adriatic initiative of January 1920. The Yugoslavs, Italians and Greeks (but not the Albanians) were all involved, to varying degrees, in forging that plan. Yugoslav Foreign Minister Ante Trumbić told the Council on 10 and 12 January that “the question can best be solved” by permitting an “independent and self-governing” Albania, according to the frontiers of 1913: the Albanians were “capable of looking after themselves”. However, “if Italy is admitted into Albania” (emphasis added), he declared, “our very existence would be at stake… Albania would become a concentration camp and centre of preparation for offensive operations all along its eastern and northern frontiers, directed against our country.”[57] If parts of Albania were awarded to Italy and Greece, Yugoslavia demanded northern Albania.

Italy’s Prime Minister Nitti offered a readjustment of the northern frontier in Yugoslavia’s favour if Italy received Fiume and the Albanian mandate, an idea endorsed by both Lloyd George and Clemenceau. On 13 January, Lloyd George handed Trumbić a pencil and a map and invited him to draw his desired frontier in northern Albania: “It was clear what he wanted,” Trumbić wrote. “To the Italians the bay of Fiume and Scutari to us!”[58] Venizelos restated the Greek demands in the south and they were conceded: “Venizelos called in & his demands in S. Albania accepted.”[59] The Compromise of 14 January proposed the Italian mandate, gave Yugoslavia control of “an autonomous province” in northern Albania (including the Drin valley and Scutari) and, awarding Koritsa to Greece, the snub to the Americans was made even more brazen by the choice of words, “the line proposed by the French and British Delegations on the Greek Affairs Commission”.[60]

Also on 14 January, like a voice from off-stage, Mehmed Bey Konitza of the Albanian delegation saw Lord Hardinge in Paris to demand Albanian independence and an extension of Albania into Montenegrin and Serbian territory (including Kosovo) that was 80% ethnically Albanian. James Headlam-Morley’s response was reminiscent of Turkhan Pasha’s “source of compensations” protest of 5 June:

I should venture to think that the difficulties about Albania are much deeper than the mere question as to the personality of Mehmed Konitza. It seems to me that they arise from the fact that in dealing with these Balkan problems the Conference ignored the principles by which the Peace should be governed, which had been set out by President Wilson. Instead of considering the interests and wishes of the population of Albania, their destiny is being determined in accordance with the principles of the balance of power between Italy, Greece and Serbia. The result is that instead of having a peace which might be the basis of a peaceful future, the settlement will be one which will leave in the minds of the peoples concerned the belief that they have not been treated with justice, and as a result we are creating occasion for future conflict… However, the harm has now been done and there seem to be no means of remedying it.[61]

No British delegate, not even Nicolson, had expressed himself in such terms during 1919; that respecting the “interests and wishes” of Albanians was now seen as the key to future peace was an indication, perhaps, that the tectonic plates were beginning to move, as shown below.

Douglas Johnson, who had President Wilson’s ear, deprecated “the triple partition of Albania” and seemed particularly annoyed that “it is the Franco-British line giving to Greece the Koritza region (the center of the Albanian national movement and the country’s richest and most advanced district), and not the American line, which is followed.”[62] Wilson’s denunciation of the new Adriatic plan on 10 February famously rejected the attempt to bully the Yugoslavs out of Fiume and Istria, but it also opposed the treatment of Albania on the grounds that “it partitions the Albanian people against their vehement protests, among three different alien Powers.”[63] The President “re-affirm[ed] that he cannot possibly approve any plan which assigns to Yugo-slavia in the northern districts of Albania territorial compensation for what she is deprived of elsewhere” and the American chargé d’affaires in Belgrade was instructed “to convey the menace that President Wilson would disinterest himself in the fate of Jugo-Slavia if she did not respect the integrity of Albania”. Leeper and Temperley both welcomed this “American démarche” in the hope that it might “make the Yugoslavs more moderate on the Albanian question” (Leeper).[64]

The eagle ascends

At the end of January, Leeper drew up a “triple mandate” scheme – north to Yugoslavia, centre to Italy, Koritsa to Greece – designed as an alternative to the outright-partition plan envisaged in the Compromise.[65] He secured the consent, he believed, of representatives of all interested parties, “French, Italians, Greeks (Venizelos!), Albanians even (with many regrets, naturally), & I hope now Yugoslavs” and won Nicolson’s admiration for “some wonderful work in getting everybody to accept an alternative solution”.[66] Regarding the Albanians, “While it does not fully satisfy their unrealisable demands for a completely independent Albania, they have admitted that they would if pressed be willing to accept it whereas if the text of the 14th January is left unmodified they would fight it to the death.”[67] The shift in the thinking of Venizelos (who was “very accessible & reasonable”[68]) was particularly significant. He not only “showed himself perfectly ready to substitute a Greek mandate for Greek sovereignty over Koritza” but even said he was prepared, if the Italians were excluded from Albania, to leave Koritsa to an independent Albania and finally admitted that the area was “not racially or linguistically Greek” and was, in fact, “the centre of Albanian nationalism”.[69] Venizelos told Aubrey Herbert “that he would resign his claim to Koritza if the Italians left Valona, but that they would not leave it” – and Leeper, looking at the full picture, said that “if you could only persuade the claimants that their rivals wanted nothing, they would all be prepared to clear out”.[70] This recalls the “best” solution – forgoing claims if one’s rivals do the same – advanced by Trumbić in January. And the Italians, too, were shifting. Castoldi told Leeper on 28 January that he favoured an outcome “by which Italy wd renounce Valona & the whole of Albania (Gk. & Yugoslav spheres included) shd be independent under a neutral mandate.”[71] When Nitti told the Yugoslavs, in London talks on 27 and 29 February, that he cared little for the Albanian mandate, Italy’s occupation having already cost “billions”, a settlement moved appreciably closer.[72]

Direct Italo-Yugoslav negotiations dragged on until Rapallo in November, delaying the settlement of the Adriatic question and its junior sibling, Albania. As Crowe put it,

The whole question is part and parcel of the Adriatic settlement which is still in a state of flux. We cannot commit ourselves to any plan without running the risk of rendering impossible such settlement as may emerge from the discussions between Italy and the Yugoslavs and with President Wilson.

It would therefore be fatal for any Minister to be drawn into any discussion on the fate of Albania, until it is known what has been settled at San Remo – and I doubt whether anything is being definitely settled there on this subject.[73]

In the meantime, the situation in Albania was transformed by “the great political reawakening of the people in 1920”.[74] Albanian assertiveness was more evident after the establishment of a new government at Lushnjë at the end of January, one that resolved to oppose partition and secure a fully independent Albania. The French withdrew from Scutari in March 1920 (and General Phillips’s small contingent left in April) and pulled out of Koritsa in May. This might have left the neighbouring states in the ascendant, but they found themselves baulked by a rising tide of Albanian resentment and belligerence. The new Minister of the Interior, Ahmet Bey Zogolli (the later King Zog), took control of Scutari to forestall the Serbs. Koritsa was taken over by the Albanian gendarmerie; the Greeks, who had mustered forces to go in, were forestalled “thanks to massive opposition from the people” (Pollo) and they held back after the British Foreign Office (prompted by Leeper) persuaded Venizelos that any such “piece-meal” measure would “prejudice any proper settlement of the Albanian question”. Greek priorities lay elsewhere, in Thrace – “The occupation of Thrace now would satisfy Greek feeling far more than the seizure of Koritza” (Leeper) – and Asia Minor, where the Greek army was soon to advance against the Turks.[75] Leeper proposed that the Greeks should satisfy themselves with occupying Argyrocastro in southern Albania, “which all the Powers (including America) are agreed in conceding to her” – but, when the Italians withdrew in June, the Albanians took the lion’s share of that district. The assassination of Essad Pasha by an Albanian nationalist on 13 June 1920, in Paris, ensured that the new government also reigned supreme in central Albania, where the Essadists had already fared badly in their struggle with Ahmet Zogolli’s forces.[76]

Popular opposition to the Italian occupation had grown as it became clear, with the publication of the January Compromise, that Italy was more likely to endorse partition than to safeguard Albania’s integrity. Albanians, disunited in many ways, shared an abhorrence of the prospect of parts of the country being handed over to Serbian and Greek rule, nor did they wish to see Valona retained by Italy. Frederick Adam believed at the start of May 1920 that “it may now require stern fighting to impose an Italian mandate on the tribesmen” and Nicolson held that, “The country is against them to a man.”[77] The Italians, counting the cost of their occupation (7,000,000,000 lire and 25,000 deaths from malaria), reduced their army in Albania to 10,000 men and withdrew to the coast. On 4 June, Albanian armed bands began to attack Valona and they besieged the city until August. Italy’s capacity to resist was undermined by soldiers who mutinied to avoid service in Albania and workers who sabotaged efforts to supply the army defending Valona. In addition, Italy’s new leaders were casting off the thinking behind the Treaty of London: Italy’s Prime Minister from June 1920, Giovanni Giolitti, and Foreign Minister Count Sforza believed that, in the latter’s words, Albania “was to come into the sphere of Italian influence, but not as a result of a juridicial situation [a mandate] wounding Albanian pride and working against the very force of Italian expansion in Albania.”[78] The protocol of 2 August between Rome and Tirana, the new capital, saw the Italians agreeing to withdraw – the last of their forces departed on 3 September – and to accept the country’s independence within the frontiers of 1913.[79]

There was an air of hope (tinged with reproof, of Lloyd George) in Wilson’s 3 November reflection that “this problem has been approached heretofore from the wrong direction, namely, that of settling the boundaries of Albania in accordance with the aspirations of Jugo-Slavia and Greece, without sufficient regard to the aspirations and rights of the Albanian people themselves. I now feel that if the prime objective is to accede to the just aspirations of the Albanian people a permanent solution of this perplexing problem may be had.”[80] Renewed conflict in the north, with Yugoslav offensives against Albanian irregulars, meant that Albania’s future was by no means settled. However, a major advance came with Albania’s admission to the League of Nations as a fully sovereign state in December 1920. In November 1921, the Conference of Ambassadors established borders which were little different from those of 1913, the changes mainly benefiting Yugoslavia in the north and east. The Ambassadors also entrusted the protection of Albania’s frontiers to Italy – Robert Vansittart wondered at the irony of a decision that “should Albania ask the League to defend her integrity, we should have recourse to those with designs upon it” – pointing towards Albania’s future role as an Italian satellite.[81] The work of boundary commissioners and other mediators continued until 1925, when Albania’s frontiers were finally settled.

Albania seemed to have entered 1919 with no more prospect of success than defeated states like Bulgaria and Hungary. However, national independence, embracing most Albanians, was achieved in the end. The Albanians succeeded because they were not, in fact, a defeated people against whom a punitive or vindictive spirit prevailed. In addition, they benefited from the inability of the Powers to agree on the sort of settlement – partition and a protectorate – that was anticipated at the beginning, and Wilson blocked the solution that the Entente devised in January 1920. Above all, the Albanians won their independence when they managed, in 1920, to summon a determination stronger than that of their enemies. The latter did not have the will to assert themselves partly because they all had greater priorities and commitments elsewhere, but also because they were concerned mostly with checking each other and much less averse to conceding the field to the Albanians. In the final analysis, nobody wanted Albania as much as the Albanians. This was a settlement which was not made in Paris; it owed nothing to the diplomacy and adjudication of the peacemakers. It was the failure of the peacemakers which was their only contribution, leaving it to the Albanians to seize the initiative and the exhausted and distracted neighbours to swallow their pride and walk away.

[1] FO 608/29, 5, Memorandum from Albanian notables, 14 November 1918.

[2] Ibid., 10, Memorandum from Albanians in the United States: Albania’s Rights, Hopes and Aspirations, n.d..

[3] FO 608/28, 430, Adamidi to Lloyd George, March 1919.

[4] The French were at Koritsa (from 1916) and there was a joint French-Italian-British occupation of Scutari. The Italians occupied most of the rest of Albania, but some Serbian forces were present in the far north.

[5] Nicola Guy, The Birth of Albania: Ethnic Nationalism, the Great Powers of World War I and the Emergence of Albanian Independence (London, 2012), 162.

[6] Harold Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919 (London, 1933), 174.

[7] Guy, The Birth of Albania, 193.

[8] Foreign Office Papers, FO 371/4355, 18-19, 22, 25, South-Eastern Europe and the Balkans, December 1918, by Allen Leeper and Harold Nicolson. Nicolson seemingly endorsed the idea that “as a whole Albanians are prepared to accept Italian trusteeship” and were concerned only that they needed a “stronger Protector” than Italy – Britain, America “or even France” – against the Serbs. FO 608/29, 427, note by Nicolson, 10 February 1919.

[9] David Hunter Miller, My Diary at the Conference of Paris, With Documents privately printed, 1918, IV, 238-42, 247-50, Outline of Tentative Report, 21 January 1919.

[10] FO 608/37, 3, Distribution of population in States of South Eastern Europe (Venizelos), 30 December 1918.

[11] Ibid., 17, Nicolson on Greek Aspirations in the Balkans and Asia Minor, 16 January 1919. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 173-74, 238, Diary, 15 January 1919.

[12] FO 608/37, 34-41, Greek Claims at the Peace Conference, 28 January 1919 (printed in War Cabinet Papers, CAB 29/7, 483). “I take the line,” Nicolson noted in his diary, “that North Epirus [is] justified, except for Koritsa.” Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 250, Diary, 27 January 1919.

[13] FO 608/37, 169, 177, Memorandum on Greek Claims by the General Staff (Thwaites) with note by Nicolson (endorsed by Crowe), 7 February 1919.

[14] Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 255-56, 268, Diary, 3, 24 February 1919.

[15] Commission on Greek Territorial Claims, FO 608/37, Procès-Verbal Nos. 2 and 3, 474-505, 18, 19 February 1919. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 264, 265, Diary, 18, 19 February 1919. On Nicolson’s dissent regarding Koritsa, see ibid., 275-83, Diary, 3, 4, 6, 12 March 1919. He later acknowledged the strength of the War Office’s strategic argument but added that it was the French “who finally persuaded us that Koritza should be given to Greece”. Ibid., 174.

[16] France’s Cambon, Gout and Laroche concurred in Crowe’s reasoning, whereas Italy’s de Martino “share[d] the views of the American delegation” regarding “the clearly Albanian character” of Koritsa. Commission on Greek Territorial Claims, FO 608/37, Procès-Verbal No. 10, 662-63, 665-68, 670-71, 4 March 1919.

[17] FO 608/46, 325, Settlement of South Eastern Europe by Nicolson, 27 March 1919, with Sketch of Treaty Regarding Northern Epirus. Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 275, 290, Diary, 3, 27 March 1919.

[18] America gave Koritsa to Albania, Britain and France gave it to Greece, and Italy stuck with the pre-war Florence Line and gave Greece nothing at all. FO 608/37, Report of Committee on Greek Territorial Claims, 603-4, 607, 6 March 1919.

[19] FO 608/29, 77, Adamidi to the American Delegation, n.d..

[20] FO 608/46, 178, note by Crowe, 4 April 1919.

[21] FO 608/29, 381, British version. FO 371/43567, 17, Frontier Lines Proposed at the Peace Conference, 1919.

[22] Ibid., 26, Andriya Radović et al, Memoire sur la Question de Scutari, 14 April 1919.

[23] Ibid., 38.

[24] FO 608/28, 412, note by Nicolson, 10 March 1919.

[25] FO 608/47, 265, note by Crowe, 16 January 1919.

[26] Ibid., 272, Crowe’s draft for Balfour to Curzon, 16 February 1919.

[27] Bejtullah Destani and Jason Tomes., eds., Albania’s Greatest Friend: Aubrey Herbert and the Making of Modern Albania: Diaries and Papers 1904-1923 (London, 2011), 267, Lord Lamington, Aubrey Herbert and Edith Durham (for the Anglo-Albanian Society) to The Times, 7 February 1919.

[28] FO 608/29, 16, Turkhan Pasha to Lloyd George, 12 February 1919, with le Memorandum relative aux Revendications Albanaises; Albanian Case: Summary and Comments by Nicolson, 20 February 1919, with note by Nicolson, 18 February 1919 and note by Crowe, n.d..

[29] FO 925/21098, Ethnographic Map of Albania (abstract) by N. Lako.

[30] FRUS, IV, 104, 111-16, Council of Ten, 24 February 1919.

[31] Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 268, Diary, 24 February 1919. Nicolson earlier described Turkhan as “very, very old and sad” whilst his colleague, Mehmed Bey Konitza, was “young and gay and witty”. Ibid., 267, Diary, 21 February 1919.

[32] Ibid., 273, Diary, 27 February 1919. Commission on Greek Territorial Claims, FO 608/37, Procès-Verbal No. 8, 617-24, 27 February 1919.

[33] FO 608/47, 267, Essad Pasha to Wilson and Balfour, 21 January 1919, with note by Nicolson, 23 January 1919. See also ibid., 289, notes by Leeper and Nicolson, 6 March 1919.

[34] Lord Hardinge added, “An Italian protectorate of Albania would be by far the best solution, but it must be on fair terms to the neighbours of Albania” – seemingly less concerned about fair terms to Albanians. FO 608/47, 293, Halil Pasha et al to Lloyd George, 4 April 1919, with notes by Nicolson, Crowe and Hardinge, 10 April 1919.

[35] FO 608/29, 119, Turkhan Pasha to Clemenceau, 14 April 1919; ibid., 121, Konitza and Tourtoulis to Clemenceau, 14 April 1919.

[36] FO 608/29, 457, note by Nicolson, 17 April 1919.

[37] Stephen Bonsal, Suitors and Suppliants: The Little Nations at Versailles (New York, 1946), 253-54, [22] April 1919.

[38] FO 608/28, 413, Adamidi to Herron, 13 March 1919, with note by Nicolson, 20 March 1919.

[39] Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919, 348, Diary, 26 May 1919. Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/2, 43, Leeper’s Diary, 26 May 1919. FO 608/29, 150, Albania Memorandum by Harold Nicolson, 28 May 1919.

[40] FO 608/29, 148, note by Crowe, 29 May 1919.

[41] Ibid., 195, Turkhan Pasha to Clemenceau, 1 June 1919. Translation by the present author.

[42] Wilson’s “Four Principles”, his February 1918 addendum to the Fourteen Points. Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States: The Paris Peace Conference 1919 (FRUS), 1918, Supplement 1, Vol. 1, 112, Address of the President to Congress, 11 February 1918.

[43] Paul Mantoux, The Deliberations of the Council of Four (Princeton, 1992), I, 495, 6 May 1919. In Hankey’s minutes, Lloyd George’s reference to Albanians cutting each other’s throats was given as “Mr. Lloyd George doubted if sufficient unity could be ensured”. FRUS, V, 483, Council of Four, 6 May 1919.

[44] Wilson to Lansing, 30 June 1919, in Guy, The Birth of Albania, 176 and Robert Larry Woodall, ‘The Albanian Problem during the Peacemaking, 1919-1920,’ PhD thesis, Memphis State University, Tennessee, 1978, 73.

[45] FO 608/28, 441, Nicolson to Balfour, 4 July 1919. Balfour agreed that the British experts should act on this basis in their private deliberations. Ibid., 444, Balfour to Nicolson, 7 July 1919 (also in Balfour Papers, Add MS 49751, f166).

[46] Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson (Princeton, 1989), Volume 61, 405, Lansing and White to Wilson, 8 July 1919; ibid., 551-54, White to Wilson, 19 July 1919. E.L. Woodward and Rohan Butler, eds., Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939 (London, 1956), First Series, Vol. IV, 19-20, Tittoni to Lloyd George, 7 July 1919.

[47] FO 608/54, 339, Crowe to Curzon, 31 July 1919. René Albrecht-Carrié, Italy at the Paris Peace Conference (New York, 1938), 242. Venizelos also agreed to neutralisation of the Corfu straits and demilitarisation of the coastline of northern Epirus.

[48] FO 608/40, 394, Italian Concessions, Draft of Note for Frank Polk, 29 August 1919. See also Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 62, 605, Polk to Wilson and Lansing, 31 August 1919.

[49] Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 62, 457, Polk to Lansing, 22 August 1919; ibid., 604, Polk to Wilson and Lansing, 31 August 1919, annotations by Wilson; ibid., Volume 63, 209, Polk to Lansing, 10 September 1919; ibid., 270-71, Tumulty to Phillips, 13 September 1919, enclosing Wilson to Polk, n.d.; ibid., 424, Wilson to Polk, 21 September 1919.

[50] T. G. Otte, ed., An Historian in Peace and War: The Diaries of Harold Temperley (Farnham and Burlington, 2014), 450, 6 August 1919. FO 371/3566, 253, Temperley to Thwaites, 8 August 1919.

[51] FO 608/28, 461, Vesnić to Clemenceau, 9 October 1919.

[52] Crowe echoed this, including the “rightly or wrongly” expression. Ibid., 465, Phillips to Thwaites, 1 October 1919, with notes by Leeper and Crowe, 24, 26 October 1919. FO 371/3571, 429, Crowe to Curzon, 3 November 1919.

[53] FO 608/29, 359, Bumçi to Clemenceau, 9 October 1919, with note by Leeper, 18 October 1919.

[54] FO 371/3571, 488, note by Oliphant, 20 December 1919. Phillips had led Britain’s small force at Scutari since December 1918.

[55] Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question (Parliamentary Paper, London, 1920), 4-5, 8-9, Joint memorandum of 9 December 1919. Leeper, who drafted this statement, had suggested that “Koritza should be left to Albania” with the Greeks compensated with minor adjustments to the east. FO 608/29, 376, Leeper to Crowe, 27 November 1919.

[56] The proposal was an advance on the earlier idea that Italy represented Albania.

[57] DBFP, First Series, II, 812-22, Notes of Meetings of 10, 12 January 1920. Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/9/1/1, La Question de l’Albanie: Extrait de l’exposé de M. Trumbić, 10 janvier 1920. See also FRUS, IX, 946, International Council of Premiers, 20 January 1920, Reply of the Yugoslav Delegation.

[58] DBFP, First Series, II, 824-27, 858-60, Notes of Meetings of 12, 13 January 1920. Ivo J. Lederer, Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference: A Study in Frontiermaking (New Haven and London, 1963), 264-65, citing the Trumbić Papers, Trumbić to Smodlaka, 23 January 1920. The Yugoslavs were clear that Scutari was offered “in compensation for Fiume”. Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/15/2, Lupis-Vukić to Seton-Watson, 14 January 1920.

[59] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 13 January 1920.

[60] Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question, 18, Revised Proposals (“the January Compromise”) of 14 January 1920.

[61] FO 371/3571, 524, note by Headlam-Morley, 9 February 1920; ibid., 527, Memorandum of Mehmed Konitza.

[62] Link, Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 64, 369, Johnson to Wilson, 29 January 1920.

[63] Correspondence relating to the Adriatic Question, 24, Wilson’s Note of 10 February 1920 (also in Beytullah Destani, ed., Albania & Kosovo: Political and Ethnic Boundaries, 1867-1946 (Slough, 1999), 520). A fuller critique of partition followed on 23 January 1920. Link, Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 64, 461-62, Polk to Wilson, 23 February 1920, enclosing draft of reply to Lloyd George and Clemenceau.

[64] H.W.V. Temperley, ed., A History of the Peace Conference of Paris (London, 1921), IV, 344. FO 371/3579, 66, Young to Curzon, 9 March 1920, with notes by Temperley and Leeper, 17, 23 March 1920.

[65] Leeper’s plan also gave Italy Valona and awarded all of the south except Koritsa to Greece, both in full sovereignty. FO 371/3575, 147, Leeper’s Proposal for the Administration of Albania. Destani, Albania & Kosovo: Political and Ethnic Boundaries, 515-17, Memorandum by Leeper, 27 January 1920 (Annex).

[66] Seton-Watson Collection, SEW/17/14/5, Leeper to Seton-Watson, 31 January 1920; ibid., SEW/17/19/1, Nicolson to Seton-Watson, 4 February 1920.

[67] FO 371/3575, 145, Leeper’s Memorandum, 5 April 1920.

[68] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 23 January 1920.

[69] FO 371/3575, 145, Leeper’s Memorandum, 5 April 1920. DBFP, First Series, XII, 132, 378, Memoranda by Leeper, 13 February, 5 April 1920.

[70] Destani and Tomes., eds., Albania’s Greatest Friend, 290, Diary, 23 March 1920.

[71] Papers of Allen Leeper (LEEP), 1/3, Leeper’s Diary, 28 January 1920.

[72] Lederer, Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference, 278-79, citing the Trumbić Papers.

[73] FO 371/3572, 33, Crowe to Hardinge, 24 April 1920. Crowe was right about the San Remo conference (19-26 April 1920), where no progress was made.

[74] Stefanaq Pollo and Arben Puto, The History of Albania, from its origins to the present day (London, 1981), 177.

[75] Pollo and Puto, History of Albania, 178. FO 371/3572, 84, notes by Leeper, Adam and Crowe, 27 May 1920; ibid., 100, Granville to Foreign Office, 31 May 1920 (Venizelos’s consent), with reply drafted by Leeper, 1 June 1920. Woodall, Albanian Problem, 237-40.

[76] FO 371/3572, 84, note by Leeper, 27 May 1920. Owen Pearson, Albania in the Twentieth Century: A History. Volume One, Albania and King Zog: Independence, Republic and Monarchy, 1908-1939 (London, 2004), I, 143-44, 147.

[77] FO 371/3572, 37, note by Adam, 1 May 1920; ibid., 110, Buchanan to Curzon, 24 May 1920, with note by Nicolson, 4 June 1920.

[78] Count Carlo Sforza, Makers of Modern Europe: Portraits and Personal Impressions and Recollections (London, 1930), 162-63. Aubrey Herbert held that, “It is not in [foreigners’] interest to swallow what they cannot digest.” And the Italian people appreciated the unwisdom of “the policy of annexing a hornets’ nest”. Destani and Tomes., eds., Albania’s Greatest Friend, 304, ‘Albania’ by Aubrey Herbert, 10 June 1920; ibid., 307, ‘Albania and the Powers’ by Aubrey Herbert, 1 July 1920.

[79] Italy kept the offshore island of Saseno (Sazan) and the Italian garrison remained at Scutari until 1921.

[80] Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 66, 307-8, Wilson to Lloyd George, 3 November 1920.

[81] Lord Vansittart, The Mist Procession: The Autobiography of Lord Vansittart (London, 1958), 295.