The great Spring Offensive launched by the Germans in March 1918 came alarmingly close to success. The redeployment of divisions from the Eastern Front (after Russia’s withdrawal from the war), Bruchmüller’s Feuerwalze (rolling barrage) and the potency of the stormtrooper units made the Germans a formidable force which sent the Allies into rapid retreat. The first and biggest attack was Operation Michael (21 March-6 April 1918), when the Germans drove back the British armies (Fifth, which broke in places, and Third) defending the line between Arras and the junction of the British and French forces on the Oise (south of the Somme). French divisions were rushed north and played a major part in stopping the Germans (at a cost of almost 60,000 casualties). Operation Georgette (9 April-1 May) involved an attack in Flanders; the French again rushed to assist the British and helped to prevent a German breakthrough. By the end of April, 47 French divisions were deployed in the British sectors and the importance of the French in stemming the German tide is beyond question; as Hindenburg later wrote, “Twice had England been saved by France at a moment of extreme crisis.”[1] Far from separating the British and French, as Ludendorff had hoped, the Spring Offensive promoted a degree of unity between the Allies. Despite many differences, the Allied armies fought side by side in the field and on 26 March 1918 all were placed under one supreme commander, Ferdinand Foch.[2]

The third main German attack, Operation Blücher on 27 May, saw Seventh Army’s advance much further south, at the Chemin des Dames, against positions held by French Sixth Army and four British divisions sent to rest and recover in an apparently quiet sector. Aided by weight of numbers (30 divisions against nine) and particularly effective use of gas in the bombardment, the Germans broke through (“everything went brilliantly” – Hindenburg) and forced a rapid retreat, 16 kms on the first day, later called the French Caporetto.[3] Britain’s Sir Henry Wilson (Chief of the Imperial General Staff) demonstrated the limits of Allied unity when, though finding the news “very disquieting”, he added that, “The Boches are increasing their attack on the Aisne up to 35 divisions and quite possibly may turn it into their main attack. I hope so. This would be good” – anything being preferable, apparently, to another attack on the British.[4]

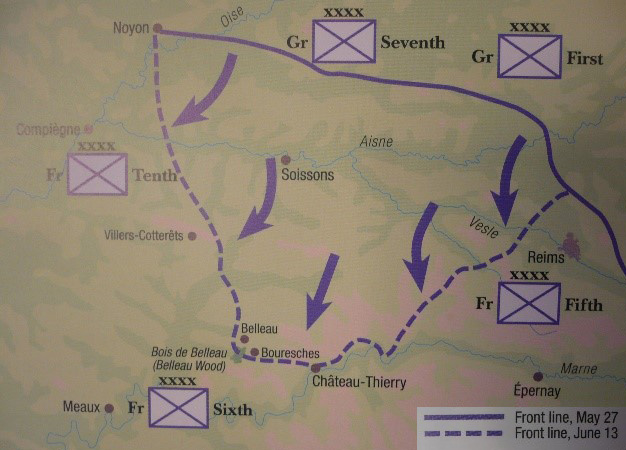

The Germans crossed the Ailette, the Chemin des Dames, the Vesle and the Aisne on 27-28 May. They continued south, between Soissons (entered late on 28 May) and Rheims, reaching the Marne on 30 May – so that the same area fought over in September 1914, at the beginning, would soon be one of the battlefields on which the outcome of the war was finally decided. Fifth Army, Ninth Army and Tenth Army were deployed to support Sixth and two American divisions were sent to Chateau Thierry on the north bank of the Marne.[5] On 31 May, American machine-gun batteries (3rd Division) and French units protected the north end of the road bridge at Chateau Thierry, covering the French crossing over the Marne, until, at 2230 hours on 1 June, the bridge was demolished, and the allies combined again to stop the Germans crossing the nearby railway bridge on 2 June.[6] On 2-3 June, American 2nd Division at Belleau, about 10 kms west of Chateau Thierry, came under heavy fire but managed to stop the German advance (“Retreat, hell! We just got here!”). On 6-15 June, 2nd Division fought the Germans to a standstill and finally cleared Belleau Wood on 25 June. The Americans suffered heavy casualties and 6 June, with 1,087 dead and wounded, was “the bloodiest day in Marine Corps history”.[7]

The Germans crossed the Ailette, the Chemin des Dames, the Vesle and the Aisne on 27-28 May. They continued south, between Soissons (entered late on 28 May) and Rheims, reaching the Marne on 30 May – so that the same area fought over in September 1914, at the beginning, would soon be one of the battlefields on which the outcome of the war was finally decided. Fifth Army, Ninth Army and Tenth Army were deployed to support Sixth and two American divisions were sent to Chateau Thierry on the north bank of the Marne.[5] On 31 May, American machine-gun batteries (3rd Division) and French units protected the north end of the road bridge at Chateau Thierry, covering the French crossing over the Marne, until, at 2230 hours on 1 June, the bridge was demolished, and the allies combined again to stop the Germans crossing the nearby railway bridge on 2 June.[6] On 2-3 June, American 2nd Division at Belleau, about 10 kms west of Chateau Thierry, came under heavy fire but managed to stop the German advance (“Retreat, hell! We just got here!”). On 6-15 June, 2nd Division fought the Germans to a standstill and finally cleared Belleau Wood on 25 June. The Americans suffered heavy casualties and 6 June, with 1,087 dead and wounded, was “the bloodiest day in Marine Corps history”.[7]

Seymour, visiting in February 1919, contended that had the Germans prevailed at Belleau Wood they “could have dominated the [Marne] valley … whereas our capture of it made possible our advance on 18 July”.[8] Inflated claims abounded. 2nd Division’s Marines (two regiments) were hailed by the American press for having “saved Paris” (only 70 kms to the west) and Woodrow Wilson “considered that [the] Allies were beaten and that America turned [the] tide and at Château Thierry saved the world.”[9] The Marines were duly honoured by the American visitors in 1919. Shotwell saw “the American line … where, in June 1918, the Germans were held back again from what looked like an easy march to Paris”.[10] Charles Thompson of Associated Press was with Wilson on 26 January 1919 when the President’s party “drove up the hill on which the American troops smashed the crack Prussian divisions mustered there to crush the “greenhorns”, and where the advance on Paris was checked… [At Chateau Thierry] Mr. Wilson saw the ruins of bridges over which the Americans thrust back the enemy line at this nearest point to Paris…”[11] At the other extreme stands Greenhalgh’s verdict that by 31 May (before Belleau Wood) “the worst was over” and after 1 June “the tide turned… [W]ith minimal British and American support” the French had stopped the German offensive.[12] The American contribution was clearly important, preventing a German advance towards Paris, and, in terms of the fighting men (the incompetent generals were a different matter), wholly admirable. But the French made up the vast majority of those who fought and stopped the Germans in the area and the Germans were utterly exhausted before they encountered any Americans.

Seymour, visiting in February 1919, contended that had the Germans prevailed at Belleau Wood they “could have dominated the [Marne] valley … whereas our capture of it made possible our advance on 18 July”.[8] Inflated claims abounded. 2nd Division’s Marines (two regiments) were hailed by the American press for having “saved Paris” (only 70 kms to the west) and Woodrow Wilson “considered that [the] Allies were beaten and that America turned [the] tide and at Château Thierry saved the world.”[9] The Marines were duly honoured by the American visitors in 1919. Shotwell saw “the American line … where, in June 1918, the Germans were held back again from what looked like an easy march to Paris”.[10] Charles Thompson of Associated Press was with Wilson on 26 January 1919 when the President’s party “drove up the hill on which the American troops smashed the crack Prussian divisions mustered there to crush the “greenhorns”, and where the advance on Paris was checked… [At Chateau Thierry] Mr. Wilson saw the ruins of bridges over which the Americans thrust back the enemy line at this nearest point to Paris…”[11] At the other extreme stands Greenhalgh’s verdict that by 31 May (before Belleau Wood) “the worst was over” and after 1 June “the tide turned… [W]ith minimal British and American support” the French had stopped the German offensive.[12] The American contribution was clearly important, preventing a German advance towards Paris, and, in terms of the fighting men (the incompetent generals were a different matter), wholly admirable. But the French made up the vast majority of those who fought and stopped the Germans in the area and the Germans were utterly exhausted before they encountered any Americans.

Another German offensive near Compiègne (Operation Gneisenau, 9 June 1918) – Britain’s Sir Henry Wilson had earlier (31 May) opined that, “If Rupprecht now attacks south from Montdidier to Noyon and takes Compiègne the French are beaten”[13] – merely took forces away from Blücher and was stymied by Mangin’s successful counter-attack on 11 June.[14] Attacks east and west of Rheims (Marneschutz, 15-17 July 1918 – “The Battle of Rheims”) quickly foundered, the French defence-in-depth functioning well to the east of Rheims (“Our guns bombarded empty trenches,” one German observed), the German bridgehead south of the Marne (crossed on 15 July) was too small and tenuously held to permit the planned drive east from Dormans to Epernay, and the Germans everywhere were badly battered by French artillery. As ever, the speed of the German advance had depleted and exhausted the troops and, going far ahead of their railheads, created supply problems. Their initial, end-of-May success yielded only a point of weakness, a salient, 50 kms wide and almost 70 kms deep, stretching south to (and then beyond) the Marne.

| The Big Berthas The notorious “Big Berthas”, heavy guns with a range of 120 kms, had bombarded Paris from 21 March 1918, the first day of the German offensive.[15] This bombardment (183 shells in all) inflicted damage and killed 256 people, and, in tandem with the possibility that the Germans might reach Paris, it caused about one-third of the population to leave the capital. On Woodrow Wilson’s second visit to the battlefields, on 23 March 1919, he and his party came upon one of the Big Bertha emplacements soon after leaving the main Rheims road to head north towards Soissons. According to Dr. Grayson,The majority of the French believe that it was this cannon that was used for the long-distance bombardment of Paris, while some of our artillery experts and most of the British dispute this. However, there is no question that it was a base for a super-cannon. In appearance it resembles very much the average railway turn-table at a railway terminal in the United States. The whole thing was very heavily camouflaged, and in the railway switches leading to the gun emplacement proper, provision had been made whereby trees could be stuck in in order to disguise the rails from aviators flying overhead… When the gun was in use it must have resembled an enormous turret such as is on battleships. The President went all around, over every section, at one place picking up a small tree and placing it in the hole across the track so he could get an idea of just how the camouflage was worked. He also went down into the great pits underneath the emplacement where the Germans kept the ammunition stored… The President and I tried to surmise to ourselves how the gun was pointed, and what distance the projectile ascended in the air, and the calculations for lack of resistance at certain heights. The President wondered what the length of time was from the moment of discharge from the gun to the landing of the projectile in Paris. The President and I both made guesses based purely on observation and in no way on any scientific knowledge of what had actually transpired. The gun emplacement is entirely 110 kilometers from Paris as the crow flies.[16] The following Sunday, James Shotwell visited a gun emplacement at Brécy: This was the site of one of the long-distance guns that shelled Paris. The [railway] switch ran into the woods not more than a couple of hundred feet… The Germans had planted little trees along the line of the track by day and removed them by night to hide the gun emplacement from aviators. The emplacement is about twenty feet in diameter and the table supporting the gun runs on ball bearings. There were pneumatic valves and the whole apparatus was a highly delicate piece of mechanism. I gathered up some nuts and bolts and on the edge of the wood a shell case which may have been used by an anti-aircraft gun. There was a big dump of ammunition and supplies still by the railroad track but otherwise no sign of war, and the fields are already plowed and the country looks prosperous.[17] Edith Wilson recalled visiting a gun emplacement on 23 March but put it further north: We left by motor at 8 a.m., taking the Paris-Soissons road and pausing at Soissons where the magnificent Cathedral had been shattered almost as badly as the one at Rheims. Then on to the original emplacement of the “Big Bertha”, in the forest near Crépy-en-Laonnais from which the Germans had shelled Paris exactly one year before to the day. We saw where the rush of flame from the muzzle had withered the trees and killed vegetation in front of the monster cannon’s position. There was a huge concrete base on which the gun had rested, and leading up to it a narrow-gauge railroad to carry ammunition. To show the very clever camouflage, this railroad led through a dense wood where the trees had been cut only in its course. Between the cross ties, metal receptacles had been sunk where the cut trees were placed except when the ammunition trains were in motion.[18] The Big Bertha in the Marne salient was finally withdrawn in late-July 1918 to prevent its capture by the advancing Allies. |

Pétain deserves much of the credit for the defensive victory of May-June 1918: his orders to prioritise the second line, according to the principle of elastic defence in depth, had been disobeyed by General Denis Duchêne on the Chemin des Dames, with fatal consequences – Gough had made the same mistake with Britain’s Fifth Army, overloading the vulnerable first line – but were followed to good effect in the subsequent engagements. Other, more attack-minded generals were credited with the great counter-offensive launched on 18 July 1918. Sir George Riddell’s diary, recording the British Premier’s visits to the area in April and June 1919, showed that Lloyd George accepted Charles Mangin’s award of the laurels of victory to Foch, Henri Gouraud and Mangin himself:

Marshal Petain sent a[n] officer to meet us who took us over the battle-fields and gave vivid explanations. L.G. repeated Gen. Mangin’s aphorism about the great battle which turned the tide… – “Foch conceived it. Gour[aud] made it possible and I did it.” This pleased our guide immensely. He repeated it several times in French and English, saying “Bon… bon … That is true!” “Foch conceived it, Gour[aud] made it possible and Mangin did it. Bon… bon… very good!”[19]

He [Lloyd George] again repeated Mangin’s saying when asked about his battle on July 18th last year – “Foch conceived it, Gouraud made it possible, and I did it.” He said, “Tomorrow we shall go to see the place where Gouraud made it possible.”[20]

The idea that “Foch conceived it” was essentially correct. Greenhalgh writes of “Foch’s July counter-offensive” and, of course, as Général en chef des armées alliées, he was in overall control. It was Foch’s offensive concept, the idea that the Allies should take every opportunity to attack and not simply sit tight until sufficient Americans arrived in 1919, which prevailed in July 1918. Pétain approved Mangin’s proposal to attack the German salient from the west and he nominated 18 July as the start date.[21] However, the Marneschutz offensive near Rheims led Pétain, ever-cautious, to suspend operations: he decided on 15 July “to retain use of his reserves for defence rather than for the planned offensive”.[22] Foch, realising that the German offensive increased the chances of a successful counter from the west, cancelled Pétain’s suspension order two hours later. General Gouraud (one arm and half a leg missing after Gallipoli) of Fourth Army “made it [Mangin’s attack] possible” by stopping Marneschutz east of Rheims, executing impeccably Pétain’s defensive concept. Then Mangin “did it”: on 18 July, his Tenth Army stormed the German salient from the forest of Villers-Cotterêts (near Soissons) and Sixth Army attacked from the south-west. Farther east, Ninth Army and Fifth Army, the latter badly mauled by Marneschutz, soon provided support as they recovered and switched from defence to attack. Thus began the Second Battle of the Marne.[23]

In April 1919, Shotwell visited the area from which Mangin attacked and saw the remains of the fortified positions (rifle pits and machine gun nests) of the German salient and signs of hard fighting, including half-a-dozen French tanks which had “been blown into a wreck by artillery”.[24] Mangin’s Tenth Army (20 French divisions, with two British and two American divisions attached) had 346 tanks as it advanced on 18 July (and Sixth Army had another 147 tanks). The French had “more tanks than we knew were in the world,” an American commented, and they forced the Germans to conclude (too late) that they had underestimated the value of tanks – but they were vulnerable to artillery, as Shotwell saw, and his belief that Paris had been “saved” by “the tanks that hid in the glades of the forest of Villers-Cotterets” overstated their role.[25] His 8 June account again showed an awareness of the two main stages of the battle, with the Germans on the attack at first (“the Germans tried to smash through towards Paris”) and then the French and their allies counter-attacking from 18 July (when the tanks, still there in June 1919, were destroyed and there was evidence of many American casualties (“an American cemetery a little beyond which must have several thousand graves”).[26]

Charles Seymour (with Isaiah Bowman, another member of the American delegation) travelled up the Ourcq valley to Villers Cotterêts on 6 April 1919, seeing some traces of the fighting of 1914 before, especially at La Ferté – “The village is badly knocked to pieces, a lot of the houses entirely destroyed” – “we got our first real touch of the fighting of last year”. He also found light relief (and some danger) in souvenir-hunting – “Gladys [Seymour] found a battered German helmet and we came on no end of empty shellcases, gas masks, etc… We picked out brand new fuses from the boxes, Mrs. Bowman saying that they would be lovely playthings for the children!” – and in climbing into wrecked tanks “in a field filled with German graves”.[27] Despite their shortcomings, in the popular imagination (and Allied propaganda) the tanks were extolled as war-winning weapons, so the attention paid to them by Shotwell and Seymour is not surprising.

Tenth Army’s attack, in combination with the other French armies’ push from the south – the similarity with the joint effort of Sixth Army and Fifth Army in September 1914 is astonishing – was designed to (and eventually did) force the Germans to retreat to the north, or even to effect their envelopment and destruction. The Allies achieved complete surprise on 18 July, giving them a great superiority in men and arms, and duly took 20,000 prisoners and advanced (through U.S. 2nd Division) eight kilometres on the first day: “Glorious Day! The Dawn of the Final Victory”.[28] But the following days’ battles were hard-fought as the Germans produced a “heroic” resistance, “fighting on three sides” and withdrawing “in good order” (Hindenburg).[29] Tenth Army was held up at Buzancy and a Franco-British (mostly Scottish) attack was to fail, after a ferocious struggle, to take it on 28 July. Charles Seymour was in this area when he “stopped on the heights southwest of Soissons to take in the lay of the land and study the bastion which the Germans held while the rest of their line to the south pivoted around, and where so many of our men were killed. I thought of how we read the news last summer and of what it meant when the word came that the Germans had been driven back of the Soissons–Château-Thierry road” about 10 kms into the salient, where three American divisions fought alongside the French.[30]

The French, British, Americans and Italians advanced from the south. This process began when the Germans evacuated their Marne bridgehead to be “saved from a Sedan” (being surrounded and captured); they left Dormans and, pressed by Ninth, completed the river crossing on 20 July, commencing a slow, fighting retreat to the north. The Germans were driven to the Ourcq (26 July) and then back from the north bank (30 July) as superior Allied resources, newly-arriving Americans (mostly with Sixth) to the fore, were brought to bear. Sixth Army’s 52nd Division took Fère-en-Tardenois, the important railway station in the centre of the German salient – Shotwell found it “a half-ruined town of some size” [31] – on 28 July. However, German machine-gun nests inflicted many losses and a French attack on Ville-en-Tardenois (20 kms east of Fère-en-Tardenois) failed on 28 July. Seymour followed the Allied armies’ route to Ville-en-Tardenois:

We went up to the Marne to Dormans where we crossed the river and followed the main road to Ville-en-Tardenois. This was a ride which I had long wanted to take, as it represented one of the two main lines of retreat of the Crown Prince’s army last July, when the Germans were trying to get themselves and their supplies out of the pocket, and where their retreat was threatened by the French, British and Italian attack between Epernay and Dormans and the French attack on the northwest near Soissons. The villages were badly battered, some of them completely destroyed, and Ville-en-Tardenois itself was in ruins. You probably remember how anxiously we waited for the news last July as to whether or not the Germans would be able to pull themselves out of the Château-Thierry salient, and what bitter fighting there was in this region. There are still many indications of a large amount of supplies which they were forced to leave behind, ammunition dumps, often made up of shells of very large caliber. This was the salient where the Americans had their first real taste of fighting.[32]

The fall of Fère-en-Tardenois on 28 July was followed by that of Ville-en-Tardenois on 2 August. The first days of August saw the Germans pull back “behind what effectively would become a moat formed by the Aisne and Vesle”.[33] With Buzancy (2 August) and Soissons (entered unopposed, also 2 August) falling to Tenth, Fismes (3-4 August) taken by the American 32nd Division, and the last of the German forces retreating across the Aisne and Vesle, the salient was no more. Allied “probing” ventures across the two rivers were beaten off by the entrenched Germans. This was where the Second Battle of the Marne came to an end, on the eve of the great British attack at Amiens.

Second Marne was primarily a French achievement. Michael Neiberg posited “the central role played by French soldiers in this battle” and cited the numbers involved – 45 French, 8 double-size American, 4 British and 2 Italian divisions – to prove the point.[34] “The battle was, literally, the turning point of the war. From that time the initiative stayed firmly in Allied hands.”[35] In Britain today, students know of the British success at Amiens on 8 August 1918, the famous “black day” of the German army, but are largely unaware of the French role in beginning the drive for victory several weeks earlier. The coordination of technologies, with artillery, infantry, tanks, cavalry and aeroplanes working together, famously decisive at Amiens, was the key to success in July: it was Second Marne which saw “the first large-scale combined arms battle” featuring all of these technologies (including a deployment of tanks (520) on 18 July that was comparable with the 552 used at Amiens).[36] Amiens followed on from the French triumph: Foch’s strategy involved “quick successive blows to keep the initiative” (Doughty), Amiens and then St. Mihiel following the Marne “to allow the enemy no respite” (Greenhalgh), and Haig had “made Fourth Army’s operation [at Amiens] contingent on Mangin’s success” at Soissons (Sheffield).[37] Neither was Amiens entirely British; the Australians and Canadians led the attack, and French First Army advanced on the right wing of Britain’s Fourth Army.

“In terms of both raw numbers of Germans who had surrendered and the tremendous shift in momentum, July 18 was significantly more important” than Amiens on 8 August and “our notion of the Hundred Days to Victory should begin with the joint triumph at the Second Marne, not the British triumph at Amiens”. Neiberg cites German concurrence: for the staff officers of Seventh Army “July 18, 1918 marks a turning point in the history of the World War”. Germany’s new Chancellor, Georg von Hertling, held that “even the most optimistic among us knew that all was lost. The history of the world was played out in three days” (between the failed offensive of 15 July and the crushing defeat of 18 July).[38]

Admittedly, there was a difference between the disciplined withdrawal of the Germans from the salient and the collapse in morale following Amiens. And, with Pétain still cautious and keen to limit French losses (‘Let the Americans and the tanks take the strain’), and Haig, in contrast, determined to push on and win the war in 1918, the British and Empire (notably Canadian) forces had the main role in the broad-front Allied push which broke the Hindenburg Line at the end of September and forced the Germans to ask for a ceasefire six weeks later. But Gary Sheffield’s view that “the blow struck on the 8 August 1918 did indeed mark the beginning of the end on the Western Front”, though conceding that “the efforts of the French, in particular, were far from negligible”, is almost as myopic as Charles Messenger’s idea that 8 August was “The day we won the war”.[39]

Of course, winning the war was a joint effort – Ludendorff acknowledged that Second Marne was “the first great setback for Germany” (emphasis added) – and Neiberg surely over-egged the pudding when he concluded that “Ludendorff’s postmortem essentially meant that he knew the war was over when the Allied counterstroke of July 18 succeeded”.[40] It was not over by any means and the British, American and French armies all rose to the challenge of finishing the job over the next three months.

The heroes of the French effort were the poilus. This was evident as much in their unyielding resistance in May as in the successful counter-offensive and in the way, reminiscent of 1914, that they moved so quickly and energetically from defence to attack. Hindenburg pointed out the contrast with “the English armies [which] had been practically spared for months” before they sprang forward in August.[41] Lloyd George, as at Verdun, acknowledged the French heroism when he visited in June 1919:

[Lloyd George]: We shall see the site of the famous battle of July 18th last year. The heroism displayed by the French was amazing. Thousands of men had to give up their lives in order to hold the front trench lightly. Clemenceau told me that as he passed these men on their way to their death he found them carrying bunches of violets and other flowers which they threw to him shouting ‘Vive la France!’”

[Riddell]: A nation which is capable of such heroism can easily be forgiven small things like the incident at Versailles.

He: I agree. They are wonderful people.[42]

In the account prepared for publication, Riddell restated Mangin’s boastful aphorism regarding “his great battle on July 18 last year – the first death blow to German hopes. To-day at Pompelle, six miles from Rheims, the Prime Minister [Lloyd George] saw how Gouraud did his part. Standing on a small chalk hillock, he saw the great slopes on which the German armies were repulsed by the gallant Frenchmen. The world little realises the sacrifices they were called upon to make in these battles.”[43] On 6 or 7 July 1918, Clemenceau had visited the Fort de la Pompelle at a time when it was under severe pressure, and in 1921, inaugurating a statue which showed him with his soldiers, he recalled meeting the defenders:

Shocky heads powdered white by the chalk of Champagne surge forth as in a dream from invisible machine-gun nests…, the flash of an eye burning with invincible resolution. Unknowable heroes… And the rugged fist holds out a little bunch of flowers covered with chalk, noble in their poverty, glorious in their meaning. Oh, those slender shrivelled stems! La Vendée shall see them, for I have sworn that they shall sleep with me…[44]

For Clemenceau, these flowers represented the poilus and their unbroken spirit and they did, indeed, sleep with him, placed in his Vendean grave on his death in 1929.[45]

[1] Marshal von Hindenburg, Out of My Life (London, 1920), 357. Elizabeth Greenhalgh is dismissive of British attempts, inspired largely by Haig’s self-serving comments, to minimise the French role and credit only the British for the ultimately successful stand. Greenhalgh, The French Army and the First World War, 275-79, 284-85. Elizabeth Greenhalgh, Victory through Coalition: Britain and France during the First World War (Cambridge, 2005), 192, 207, 211. See also Doughty, Pyrrhic Victory, 432-40.

[2] On the continuing differences, with almost as much conflict between Foch and Haig as between Foch and Pétain, his colleague, see Greenhalgh, Victory through Coalition, 197 et seq.. An even-handed treatment of the “anxieties, mutual suspicion, the resurgence of national interests and, above all, misunderstandings” that threatened the Alliance is given in Gary Sheffield, The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army (London, 2012), 271-86.

[3] Hindenburg, Out of My Life, 360. Pétain had compared British Fifth Army’s defeat in March to the Italian performance at Caporetto. Doughty, Pyrrhic Victory, 437.

[4] C.E. Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, His Life and Diaries (London, 1927), II, 101-2, Diary, 27, 28 May 1918.

[5] The map shown here is from David Bonk, Château Thierry & Belleau Wood 1918: America’s baptism of fire on the Marne (Oxford, 2007), 72.

[6] The Wilson party of visitors in January 1919 “proceeded by motor to Chateau Thierry and crossed the

bridge to the railroad station. The bridge we passed had been blown up by the French retreating from Chateau Thierry killing many Germans, who were crossing at the time of the explosion.” Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 54, 279, Diary of Dr Grayson, 26 January 1919.

[7] Bonk, Château Thierry & Belleau Wood 1918, 55, 66.

[8] Letters from Charles Seymour, 150, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 2 February 1919.

[9] Diary of George Louis Beer, 10 December 1918, quoted in Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 74. On 22 December 1918, Wilson visited a hospital at Neuilly and hundreds of wounded Americans who “had participated in the great battle at Chateau Thierry” – Grayson was probably conflating Belleau Wood, the larger battle, with Chateau Thierry – “which turned the tide of the entire war.” The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume, 53, 467, Diary of Dr Grayson, 22 December 1918.

[10] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 236, Diary, 30 March 1919.

[11] The New York Times, 28 January 1919. On Wilson’s visit, see Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 54, 278, Diary of Dr Grayson, 26 January 1919. Hall and Seymour also visited Chateau Thierry and Belleau Wood. Hall’s memoir, 18 December 1918, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 97-98. Letters from Charles Seymour, 150-51, 199-200, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 2 February and 7 April 1919.

[12] Greenhalgh, The French Army and the First World War, 297-98, 310-11.

[13] Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, His Life and Diaries, II, 103, Diary, 31 May 1918.

[14] Robert Asprey has been very critical of Ludendorff’s diversion of forces from Blücher and the Marne. Robert B. Asprey, The German High Command at War: Hindenburg and Ludendorff and the First World War (London, 1994), 423-24.

[15] They were called Big Berthas by the Allies, who borrowed a term used by the Germans earlier in the war to describe somewhat lighter guns.

[16] Link, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 56, 195-96, Diary of Dr. Grayson, 23 March 1919.

[17] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 237, Diary, 30 March 1919.

[18] Edith Wilson, My Memoir, 252. See also Hall’s memoir, July 1919, in Higonnet, Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 167.

[19] Riddell Diaries (BL), Add MS 62963, f85, Diary, 20 April 1919 (also in Riddell, Intimate Diary, 54 and McEwen, The Riddell Diaries, 268).

[20] Riddell Diaries (BL), Add MS 62964, f16, Diary 17 June 1919 (also, in part, in Riddell, Intimate Diary, 92).

[21] The genesis of the proposal is succinctly described in Doughty, Pyrrhic Victory, 467.

[22] Greenhalgh, The French Army and the First World War, 314-16.

[23] Foch proudly told Wilson of his overruling of Pétain. Callwell, Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, His Life and Diaries, II, 117, Diary, 22 July 1918. “More than any other single person, [Foch] is responsible for the Allied victory on the Marne.” Michael S. Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne (Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2008), 45. Churchill visited Mangin’s HQ at the end of July 1918 and the victorious general voiced his aphorism during their private conversation. “Some years afterwards when I repeated these words to General Gouraud, he considered them for an appreciable moment, then said ‘That is quite true’.” Paul Greenwood, The Second Battle of the Marne 1918 (Shrewsbury, 1998), 171.

[24] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 249-50, 6 April 1919.

[25] Ibid.. Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne, 123, 131. Greenwood, The Second Battle of the Marne, 192-93.

[26] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 364-66, 8 June 1919.

[27] Letters from Charles Seymour, 195-96, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 7 April 1919.

[28] Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne, 127, quoting a French regimental history.

[29] Hindenburg, Out of My Life, 383.

[30] Letters from Charles Seymour, 196, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 7 April 1919. Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne, 128.

[31] Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference, 237, Diary, 30 March 1919.

[32] Letters from Charles Seymour, 231-32, Seymour to Mr and Mrs Thomas Watkins, 21 May 1919.

[33] Greenwood, The Second Battle of the Marne, 179.

[34] Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne, 128, 184.

[35] Greenwood, The Second Battle of the Marne, 194.

[36] Greenhalgh, The French Army and the First World War, 316.

[37] Doughty, Pyrrhic Victory, 474. Greenhalgh, Victory through Coalition, 248. Sheffield, The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army, 294.

[38] Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne, 130-32, 188. See also Greenwood, The Second Battle of the Marne, 191-93. General Friedrich von Lossberg called 18 July “the precise turning point in the conduct of the war”. Asprey, The German High Command at War, 442.

[39] Sheffield’s only quibble, far from crediting the French effort of 18 July, is that the (British) Battle of Albert on 23 August was “even more significant” than Amiens. Sheffield, The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army, 5, 8, 287, 296, 299, 307-8, 337-38. Charles Messenger, The day we won the war: turning point at Amiens, 8 August 1918 (London, 2008).

[40] Neiberg, The Second Battle of the Marne, 185.

[41] Hindenburg, Out of My Life, 386.

[42] Riddell Diaries (BL), Add MS 62964, ff16-17, Diary 17 June 1919 (also, in part, in Riddell, Intimate Diary, 92. Clemenceau “was passed by thousands of his countrymen who knew that they were marching to certain death”. Ibid., 95). The “incident at Versailles” involved the stoning of the German delegates by the people of Versailles.

[43] Riddell Diaries (BL), Add MS 62964, f21, Riddell’s Account (also in Riddell, Intimate Diary, 95).

[44] The New York Times, 29 January 1922.

[45] A caption in the museum at Fort de la Pompelle puts the encounter with the poilus at the fort, but the precise location is not certain. Samuël Tomei, Clemenceau au Front (Paris, 2015), 121-24.